Los Angeles Superior Court

111 North Hill Street

Los Angeles, CA

USA 90012

Re: Rambam v Prytulak BC271433 James R. Dunn

James R. Dunn:

Three Documents Call for a Reply

Defendant Lubomyr Prytulak has received three documents relating to Rambam v Prytulak BC271433 which necessitate a response. The three documents will be identified by the names shown in bold below:

Minute-Order-20-Dec-2002, received by Lubomyr Prytulak by mail 30-Dec-2002.

Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003, which is the Plaintiff Steven Rambam reply to the above minute order, and which is titled PLAINTIFF'S OPPOSITION TO ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE RE RECONSIDERATION OF ISSUES REGARDING PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER DEFENDANT, and which was received by Lubomyr Prytulak by mail on 14-Jan-2003.

Minute-Order-25-Nov-2002, which came attached as Exhibit 1 to the above Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003, and which details the Court disposition of Prytulak Motion-to-Quash-D.

A Delay Which Further Evidences Court Prejudice

Defendant Lubomyr Prytulak is grateful for Gary Kurtz having mailed him a copy of the James R. Dunn Minute-Order-25-Nov-2002 which informs Lubomyr Prytulak of the Court disposition of Prytulak Motion-to-Quash-D heard on that same date. However, Lubomyr Prytulak points out as well that his not being served with this minute order until 14-Jan-2003 interposes a more than seven-week delay between the decision and either Court or Kurtz supplying Lubomyr Prytulak with the minute order which explains that decision, which unconscionable delay adds to the accumulation of evidence that the Court is prejudiced against Lubomyr Prytulak, and blocks his access to information, and obstructs his every move.

Exacerbating the neglect of Gary Kurtz and the Court is that Lubomyr Prytulak served both of them on 03-Dec-2002 with a Prytulak-Request-for-Minute-Order, which asked for � among other things � a remedying of this particular neglect.

Lubomyr Prytulak continues to list this Prytulak-Request-for-Minute-Order among the documents spoliated for four reasons:

The Minute-Order-25-Nov-2002 was delivered to Lubomyr Prytulak on 14-Jan-2003 � six weeks after his Prytulak-Request-for-Minute-Order was delivered to the Court � such that it is not obvious that the late delivery was a response to the request.

The Minute-Order-25-Nov-2002 was mailed to Lubomyr Prytulak not by the Court itself, but only by Plaintiff lawyer Gary Kurtz, whereas Lubomyr Prytulak requires that Court orders in response to Prytulak motions be delivered by the Court, and not filtered through a Plaintiff who is notorious both for his animosity toward Lubomyr Prytulak and for his lack of veracity. Lubomyr Prytulak is no more satisfied with being able to learn of Court orders only through Gary Kurtz than Gary Kurtz would be to learn of Court orders only through Lubomyr Prytulak.

The Prytulak-Request-for-Minute-Order has never been acknowledged in the Los Angeles Superior Court online Case Summary.

The Prytulak-Request-for-Minute-Order did more than request a copy of the minute order, and its other requests have neither been answered or satisfied.

The Kurtz-Rambam VNN Hoax Rekindled

In support of the Gary Kurtz vocabulary-challenged assertion that "Defendant is a bad man," (Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003, p. 3, line 25), Gary Kurtz renews his defamatory accusation that Lubomyr Prytulak is a contributor to a neo-Nazi web page (Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003, p. 3. lines 25-28).

When Gary Kurtz first proffered this accusation in his Rambam-Opposition-12-Nov-2002, Lubomyr Prytulak demonstrated that the accusation was not only false, but obviously fraudulent, in his Prytulak-Reply-D7 (dated 21-Nov-2002) � particularly in the section titled Kurtz and Rambam play their last card, which is the 39-page-long VNN Hoax. The refutation in Prytulak-Reply-D7 was served on Gary Kurtz on 22-Nov-2002, and at 09:22am was signed for at Gary Kurtz's office by D. Engel. Thus, the Gary Kurtz defense of honest mistake, unavailable for the first presentation of the VNN Hoax in Rambam-Opposition-12-Nov-2002, becomes doubly unavailable for the second presentation in Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003. Rather, both presentations of the VNN Hoax, but especially the second, must have been knowingly fraudulent and malicious.

It can be added to the reasons why Gary Kurtz and Steven Rambam knew, or should have known, that their accusation of Lubomyr Prytulak Neo-Nazi sympathies was false was the longstanding publication on Lubomyr Prytulak's web site, UKAR (the Ukrainian Archive at www.ukar.org), of numerous such statements as the following:

The brutality of the German regime became evident everywhere. |

Similar anti-Nazi writing can be found on UKAR at several locations, most particularly in the section titled Were Ukrainians Really Devoted Nazis? in the Lubomyr Prytulak essay, The Ugly Face of 60 Minutes.

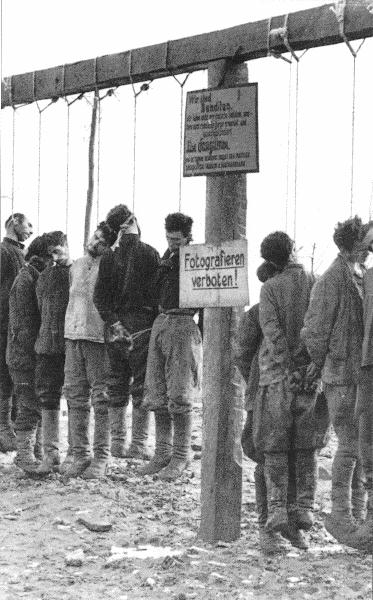

Published on UKAR (the Ukrainian Archive at www.ukar.org) with the caption Partisans executed by the Nazis January, 1943. |

|

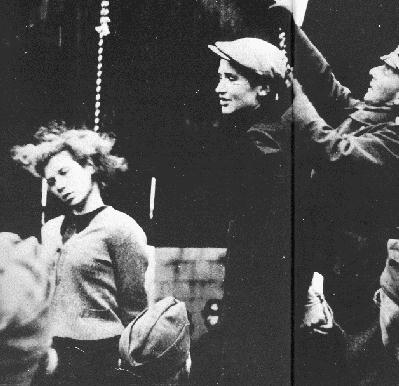

Gary Kurtz and Steven Rambam would not even have had to do much reading to recognize the powerful anti-Nazi inclination of UKAR � they could have more effortlessly noticed photographs documenting Nazis hanging Slavs, which send a powerful anti-Nazi message, as for example the three appearing here, all of which have been on UKAR for years.

Published on UKAR (the Ukrainian Archive at www.ukar.org) with the caption Young woman executed by the Nazis, and young man about to be executed, for partisan activities. |

|

Keith Simpson, Waffen SS, Bison Books, London, 1990, p. 47. The caption which Keith Simpson gives this photograph is "Waffen SS and army soldiers taking 'snapshots' of executed Soviet partisans." This photograph has been available on UKAR since 16-Aug-1999 at Prytulak-to-Arad: The Germans brought cameras. |

|

And Gary Kurtz and Steven Rambam would not even have had to review the contents of UKAR at all to divine its unmistakable anti-Nazi commitment � though before levelling a charge as injurious as neo-Nazism, they did have an obligation to. It would have sufficed for them to glance at the UKAR home page where they would have found the unequivocal image on the right which all by itself should have warned them away from staging their VNN Hoax.

Thus it is amply evident that the Gary Kurtz and Steven Rambam defense of their VNN Hoax as an understandable mistake would be no more available for the first staging of their VNN Hoax than it would be for the second. The Gary Kurtz and Steven Rambam VNN Hoax stands to their discredit, even as it stands to the discredit of the Los Angeles Superior Court for having supplied the two hoaxers with a stage, and for having encouraged them by spoliating Prytulak documents which blew away their smoke and knocked down their mirrors.

The supportive role of the Los Angeles Superior Court in the Kurtz-Rambam defamation deserves to be underlined. The Court begins by filing the Gary Kurtz defamation contained in Rambam-Opposition-12-Nov-2002. The Court subsequently is served with the Prytulak-Reply-D7 which contains the Prytulak refutation. This Prytulak document is delivered to the Court on 22-Nov-2002 at 09:51am, and is signed for by L. Jackson; however, the Court refuses to file it, as usual offering no explanation for its refusal. Following that, the Court informs Lubomyr Prytulak in its Minute-Order-20-Dec-2002 that it will accept no further submissions from him, and following which Lubomyr Prytulak receives a repetition of the VNN-Hoax defamation in the Gary Kurtz Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003, which the Court does file, but to which the Superior Court forbids Lubomyr Prytulak to reply. The Court filing defamatory statements from the direction of the Plaintiff, while greeting Defendant answers to the defamation first with spoliation and later with a refusal to accept further submissions, testifies to the unfairness of the court, and drags the administration of justice in Los Angeles into deeper disrepute.

The Gary Kurtz and Steven Rambam VNN Hoax has as its aim the same character assassination that the duo attempted in their accusations that Lubomyr Prytulak is motivated by "religious discrimination" and is guilty of something "akin to a hate crime":

|

Prytulak's motivation is based on religious discrimination and his extreme political leanings. This is akin to a hate crime, which I believe should be harshly punished.

|

Lubomyr Prytulak trusts that the Court had the presence of mind to enquire precisely what religious groups Steven Rambam had in mind when he levelled the above defamation, and what evidence he was relying on. One obstacle to Steven Rambam arriving at any easy conclusion is that Lubomyr Prytulak reserves his harshest criticism for Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma, and on the other hand when evaluating Jewish leadership, Lubomyr Prytulak places his trust almost exclusively on such Jewish writers as the following, whose work he quotes not only with approval but with admiration, and in several cases at length and in more than one document on UKAR:

|

The Google search engine available on the UKAR home page is able to discover instances in which the above writers are cited or quoted in more than one UKAR document.

At times when the Los Angeles Superior Court is predisposed to indulge Gary Kurtz in this line of defamation, the Court might find it instructive to ask him to address the question of how he infers "religious discrimination" from the observation of Lubomyr Prytulak backing certain Ukrainian factions against others, while at the same time backing certain Jewish factions against others. Indeed, the Ukrainian Archive can be viewed as, more than anything, a platform for the promotion of Jewish authorship, such that the expurgation of Jewish writing from UKAR would gut it of its main themes, whereas the expurgation of Ukrainian writing would leave it little changed. Steven Rambam will particularly recall that much of the writing to which he personally objects was penned by a man of great courage and integrity, the recently-deceased Robert I. Friedman, who as long ago as 1990 was publishing statements like the following, without Steven Rambam (who in New York sports the surname Rombom) venturing to sue him:

|

The Court is Without Authority to Silence Lubomyr Prytulak

A look at today's online Case Summary for BC271433 reveals that 16 entries are identified as "Filed by Attorney for Pltf/Petnr," whereas only 2 entries are identified as "Filed by Attorney for Defendant/Respondent," these two denoting the submission on the same day of identical copies of a single Prytulak Motion-to-Quash-D. This inadequacy of Prytulak representation in the trial record results from Court spoliation of six out of seven Prytulak submissions. (Furthermore, the Court has never given any indication that it has read or in any way been influenced by the sole Prytulak submission that has been filed, Motion-to-Quash-D, thus while giving Lubomyr Prytulak trivial representation in the Case Summary of the Court, giving him no representation in the deliberation of the Court.)

On top of that, the James R. Dunn Minute-Order-20-Dec-2002 places on the table two new proposals, namely that

"The court will not entertain further papers from the defendant, who is currently in default," and that

the Court proposes to act on its own motion, which may imply that the single filed Prytulak Motion-to-Quash-D will now be ignored officially, as it has been ignored up to now unofficially.

The instant Superior Court, then, gives the impression of announcing its intention to avoid reading anything that Lubomyr Prytulak either has written in the past or that he might write in the future, which gives the appearance of an intention to abandon all semblance of an adversarial procedure in a court of law in favor of proceedings resembling a Soviet-era show trial.

If the justification for the Court refusing to entertain further papers from Lubomyr Prytulak is that he "is currently in default," then the Court is at variance with the weighty precedent that has been cited in Prytulak-Reply-D3 (dated 05-Nov-2002, and served upon both Court and Gary Kurtz on 07-Nov-2002), where it is demonstrated that the colorful language that is often quoted in California cases � "A defendant against whom a default is entered is out of court and is not entitled to take any further steps" � invites misunderstanding and misapplication, as can be read particularly in the Prytulak-Reply-D3 section titled Simultaneous Motions to Quash Service and Vacate Default. The position of Gary Kurtz and the Court appears to be that they have a right to their erroneous interpretation of the "out of court" statement above, and need not be persuaded by substantial legal authority of what that statement really means, because the Prytulak citation of that authority lies buried in a document which the Court has chosen to spoliate. In their minds, perhaps, all future spoliation is permitted on the basis of their same misinterpretation of the meaning of "out of court," which their continuing spoliation forever protects them from learning the correct meaning of, in a vicious and unbreakable circle.

The reality that Gary Kurtz and the Court willfully blind themselves to is that a defendant in default is "out of court" in one sense only � he is "out of court" with regard to the estimation of damages which is needed for default judgment. However, defendant is not "out of court" with regard to other matters, as for example with regard to vacating default, and most emphatically not with regard to vacating default by challenging jurisdiction, for which voluminous authority is cited in Prytulak-Reply-D3, the most important of all the submissions that the Los Angeles Superior Court has spoliated.

The short of it is that the Court is never entitled to clap its hands over its ears whenever a defendant speaks, for the simple reason that the defendant may be attempting to offer the court compelling reason why it is without authority to clap its hands over its ears whenever he speaks. In the instant case, the Court is without authority to spoliate documents, or to leave them unread, because those documents may be capable of convincing the Court that it is obligated to file those documents, and to read them. In the absence of the Court reading and understanding all spoliated documents, and most importantly the spoliated Prytulak-Reply-D3, it has small chance of arriving at a fair decision in its upcoming hearing of 10-Feb-2003, or thereafter.

Looking Beneath the Surface of the Pavlovich Decision

Gary Kurtz upholds his reputation for perverting the significance of the cases he cites when he maintains in his Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003, pp. 2-3 that the Pavlovich case addresses jurisdictional issues only, and so is not helpful in answering the question of whether jurisdiction failure is permitted to vacate default. The Pavlovich case might indeed appear irrelevant upon superficial scrutiny, as for example upon a reading of only the 25-Nov-2002 Pavlovich decision, Pavlovich v Santa Clara Superior Court (accessible in either pdf or html formats) which in fact makes not a single reference to default, and thus not to the circumstances which permit setting aside or vacating default. However, broader reading of the Pavlovich case is productive of the discovery that the jurisdiction-failure-vacating-default that Gary Kurtz decries as an impossibility was in fact admitted as a permissible option in Pavlovich without either the Santa Clara Superior Court or the California Court of Appeal or the California Supreme Court batting an eye.

Specifically, the Matthew Pavlovich case � (DVD Copy Control Association, Inc v Andrew McLaughlin) when it was before the Santa Clara Superior Court, Case No. CV 786804, argued by Allonn E. Levy � shows a face page carrying the title MOTION TO QUASH SERVICE OF SUMMONS FOR LACK OF JURISDICTION, a title that pays not even lip service to vacating default. Within the body of the motion, however, vacating default is frequently requested, though never by means of separate arguments, but merely as a logical consequence of quashing service:

|

Accordingly, this Court must quash service of process and set aside any existing default or default judgment as void (C.C.P. �473(d); C.C.P. �418.10(d)).

|

If attorney Allonn E. Levy is able to get his above motion � which bundles vacating default with quashing service � filed and heard in Santa Clara, Defendant Prytulak has trouble comprehending why he has faced, and continues to face, such fierce resistance to getting his very similar motion � which also bundles vacating default with quashing service � either filed or heard in Los Angeles.

Among the materials found in Electronic Frontier Foundation coverage of Pavlovich proceedings that went to the Court of Appeal of the State of California, Sixth Appellate District, is the following affirmation of the propriety of challenging jurisdiction while simultaneously requesting the vacating of default:

Where a defendant attacks jurisdiction post default, the proper mechanism is to file a motion to concurrently vacate default or default judgment and quashing service of process (Floveyor Int. Ltd v. Superior Court (1997) 59 Cal.App.4th 789, 792). It is then the plaintiff's burden both to prove proper service of process and to prove the existence of personal jurisdiction over the defendant (Id at 792-793).

|

Thus, Gary Kurtz is � true to form � in error when he summarizes the entire Pavlovich case (after having read only the Pavlovich Supreme Court decision) that:

The case makes no mention of an untimely motion, a motion filed without proper leave to file an untimely motion, a motion to set aside default, [...].

|

And Lubomyr Prytulak does not offer the Pavlovich case as his only authority, or even as his main authority, for the proposition that an efficient and time-honored tool for vacating default is the demonstration of jurisdiction failure. Rather, Lubomyr Prytulak has gathered an array of precedents, and has presented these in his Prytulak-Reply-D3, particularly under the heading Simultaneous Motions to Quash Service and Vacate Default. Had the Court not spoliated its copy of this Prytulak submission, then Gary Kurtz might have been discouraged from ignoring the copy which Lubomyr Prytulak served him with, such that he might today be complying with the law cited therein rather than wasting everybody's time with baseless assertions.

Wasting everybody's time is not the worst of it. The worst of it is that Gary Kurtz is inviting the instant Superior Court down the path to embarrassment. That is, the 25-Nov-2002 Pavlovich California Supreme Court decision is one of the most widely noticed of the day, and Gary Kurtz's recommendation that the instant Court disallow in Rambam v Prytulak the possibility of jurisdiction-failure-vacating-default is a recommendation that the Los Angeles Superior Court disallow a possibility that was allowed in Pavlovich by the Santa Clara Superior Court, and with the subsequent approval of the California Court of Appeal, and then after that with the approval of the California Supreme Court.

Formatting and Procedural Requirements

In the first place, all of Lubomyr Prytulak's labors have had, and continue to have, as their sole aim to challenge jurisdiction, and the Court is required to respond to such a challenge even if it appears as a mere suggestion, and even if its presentation is informal, and in fact "it makes no difference how the question comes to its attention." This is amply documented in the Court-spoliated Prytulak-Reply-D3, especially in the section titled Jurisdiction can be challenged at any time, and at any stage of proceedings, and in any manner.

Furthermore, Defendant Lubomyr Prytulak understands formatting and procedural requirements to apply to submissions from litigants over whom the Court has jurisdiction. Lubomyr Prytulak has searched for, and failed to find, any statutes dictating format or procedural requirements applicable to individuals like himself over whom the Court lacks jurisdiction. When Gary Kurtz brings such as-yet-undiscovered statutes to Lubomyr Prytulak's attention, then Lubomyr Prytulak will be pleased to read them and consider how he should modify his conduct. In the absence of such statutes � that is, statutes directed at individuals over whom the Court lacks jurisdiction � Lubomyr Prytulak views the Los Angeles Superior Court as having no more authority to dictate that Lubomyr Prytulak comply with such formatting or procedural requirements as that he should write to the Court only on recycled paper (California Rule of Court 989.1), than Lubomyr Prytulak would have authority to demand that the Court write to him only on yellow paper. Lubomyr Prytulak strives to supply the Court with information that is relevant and arguments that are logical, and leaves unhefted those additional burdens which Gary Kurtz points to, but which Lubomyr Prytulak is under no obligation to bear.

Finally, when Lubomyr Prytulak had earlier elected to follow the path which offered to most expeditiously bring proceedings to a just conclusion � the path of complying even where he saw no legal obligation to comply � he received no cooperation from the Court. That is, on numerous occasions Lubomyr Prytulak begged for feedback as to how he should amend his submissions to make them acceptable to the Court, and was invariably met with stony silence.

The Gary Kurtz complaint of formatting or procedural shortfalls in Prytulak submissions is not new, and neither are Prytulak replies, which if the instant Superior Court did not spoliate, would surely have had the effect of reducing Gary Kurtz repetition of his unfounded complaints, and thus would render unecessary the Lubomyr Prytulak repetition of adducing authority demonstrating how those complaints were unfounded.

High Time to Bury the New York Award

If the Superior Court at the outset had instructed Gary Kurtz to stop citing the putative Rambam victory in a jury trial in New York which he claims has awarded Rambam $850,000, this distracting piece of irrelevancy might today not be cluttering up Gary Kurtz submissions, as it does in his Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003, p. 1, lines 3-5. If the Court does not have any California authorities at hand, perhaps Gary Kurtz could be silenced merely with the following Washington authority:

[I]t is clear [that] citation to unpublished opinions of this court is forbidden and citation to unpublished opinions of other jurisdictions is also inappropriate. "The reliance upon unpublished opinions is a dubious practice at best, and we decline the invitation under the present circumstances." State v. Sparkman & McLean Co., 16 Wash. App. 402, 406, 556 P.2d 946 (1976).

|

The authority above disallows reliance on "unpublished opinions," but Gary Kurtz submits not an unpublished opinion, but no opinion at all, and rather only a single inscrutable sheet of clerical scribbling which gives no information of what evidence was presented at trial, or what arguments were made, or what questions the jury decided. If the instant Court could instruct Kurtz and Rambam to begin celebrating their putative New York victory in private, and not on the pages of their litigation submissions, not only would it be removed as a distraction, but perhaps Rambam and Kurtz would be advanced a step toward a recognition of the lack of underpinning of their case, not to mention toward a maturer understanding of legal reasoning.

Gary Kurtz Misrepresents Schlyen v Schlyen

There is one place in the Kurtz Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003 that did give pause and that did call for a moment's contemplation, alleging as it did that missing a response deadline was attorning to personal jurisdiction, which would be the same as saying that a court entering default could be equated with a defendant attorning to personal jurisdiction:

Failure to file a timely objection to personal jurisdiction is a waiver. Schlyen v. Schlyen, 43 Cal.2d 361 (1954).

|

Our first signal that Gary Kurtz is citing Schlyen v. Schlyen inappositely arrives when searches through the decision for the strings "default" (which would also discover "defaults" and "defaulted" and "defaulting") and for "personal jurisdiction" reveals that these are absent. In confirmation of that initial signal of irrelevance, a reading of the decision reveals that it concerns which of two or more courts has jurisdiction, and in case of a failure to timely object to whichever happens to be the instant court, then the instant court does become the court of jurisdiction by waiver. Among the complications of Schlyen v. Schlyen are (1) that the same court can sit in more than one role, as for example a court of general jurisdiction can sit as a court of probate; and (2) that the situations contemplated are ones in which the jurisdictions of the alternative courts are not exclusive. The summary of Schlyen v Schlyen in its final paragraph demonstrates that the sole question that the judgment addresses is which of two courts should take jurisdiction, or in what capacity a given court should sit:

From the foregoing it is concluded: (1) that the superior court has general jurisdiction in equity cases such as the present one; (2) that in the absence of a demurrer answer, motion or other timely objection on the ground that the issues involved should be tried in probate, the superior court may adjudicate those issues with the same force and effect as if the objection had not been made; (3) that when as here the issues pertain only to the rights of parties in privity with the estate and do not involve the rights of third parties or strangers to the estate the superior court sitting in probate has jurisdiction and should adjudicate them, but that such jurisdiction is not exclusive, depending on the facts of the particular case and may be waived; (4) that under the undisputed facts of this case the defendant did not timely interpose her objection to the trial of the issues by the superior court sitting in the exercise of its general equity jurisdiction and therefore waived the objection, and (5) that when such objection is timely made the trial court should not dismiss the action but should try it as a matter in probate to the end that property wrongfully claimed by the representative of the estate be included in the assets of the estate.

|

Schlyen v Schlyen, in other words, has nothing to say about waiving personal jurisdiction, has not the slightest relevance to Rambam v Prytulak, and contributes nothing to a clarification of any of its issues. Most emphatically, Schlyen v Schlyen does not at all support the Gary Kurtz conclusion that "Failure to file a timely objection to personal jurisdiction is a waiver."

A consideration of Schlyen v Schlyen refreshes our recognition that Rambam lawyer Gary Kurtz tosses off citations casually and irresponsibly, at his best quoting snippets torn out of context, and at his worst � as here � simply misrepresenting a judgment without quoting anything. The thread on which Gary Kurtz hangs his conclusion in the instant example is the thinnest imaginable � that the Kurtz one-sentence summary of Schlyen v Schlyen is justified because it contains the words "timely," "jurisdiction," and "waiver," and so does the Schlyen v Schlyen decision. His legal training fails to warn him that the mere sharing of three words, no matter how juxtaposed or in what context embedded, is insufficient to establish a congruence of meaning. Rambam lawyer Gary Kurtz understands litigation as slinging at his opponent a stream of deceptions in the hope that a few might not be deflected, and on the expectation born of experience that the many that are deflected will bring him no penalty. Governed by such a modus operandi, Rambam lawyer Gary Kurtz puts both Defendant Lubomyr Prytulak and the Los Angeles Superior Court to needless labor sifting through a mountain of his errors, misrepresentations, and irrelevancies.

In contrast to Gary Kurtz, the Court might notice upon any future filing of the currently Court-spoliated Prytulak-Reply-D3 that it lists 116 entries in its Table of Authorities, inclusive of statutes, every one of which can be found to be represented accurately and responsibly within the body of the document.

Gary Kurtz Misrepresents Abelleira v District Court of Appeal

Gary Kurtz states that the Los Angeles Superior Court lacks authority to examine personal jurisdiction on its own motion, and cites the authority of Abelleira v District Court of Appeal:

It is well settled that this Court has supervisory and inherent powers to carry out its duties. [Citation] It is also often stated that the Superior Court has inherent power to examine its jurisdiction on its own motion, however, that rule of law does not apply to issues of personal jurisdiction. In Abelleira v. District Court of Appeal, 17 Cal.2d 280, 302-04 (1941), the California Supreme Court defined the meaning of that language as follows:

But once the tribunal, judicial or administrative, has made this determination of the issue, and has acted to assume jurisdiction of the cause, the rule no longer has any meaning. The jurisdiction to determine jurisdiction has been fully exercised by a determination in favor of jurisdiction over the cause; the question is no longer of jurisdiction to determine, but of jurisdiction to act.

Id. at 303. In other words, the jurisdiction to examine jurisdiction relates to subject matter jurisdiction and similar questions of the court's power over the issues, not the parties. Cases that have followed Abelleria are consistent.

|

To fully appreciate the magnitude of Gary Kurtz's misrepresentation of Abelleira, one needs only read the context. (Below, the passage that Gary Kurtz quoted is rendered in blue, and explanatory material that Lubomyr Prytulak inserted within square brackets is rendered in red.)

The proposition, stated simply, is that a tribunal has jurisdiction to determine its own jurisdiction. This is a truism, and, subject to certain implicit limitations, is ordinarily a correct statement of law. It has its origin mainly in the cases holding that a court has inherent power to inquire into jurisdiction of its own motion, regardless of whether the question is raised by the litigants. [...] It means only that the trial court or lower tribunal or body to which the question [of jurisdiction] is submitted has such jurisdiction to make the first preliminary determination [of jurisdiction] � not a final one; and no interference is permitted until it does decide the matter one way or the other. Until it acts to assume or refuse jurisdiction over the merits no one is entitled to complain [of what may appear to be an imminent jurisdictional decision, as for example to complain by issuing a writ of prohibition]. |

Quite simply, the "rule" which Abelleira enunciates above is that a higher court � whether on the motion of a petitioner or on its own motion � cannot interfere with a lower court's evaluation of its own jurisdiction while that evaluation is in progress, but is capable of reversing that lower court's decision concerning jurisdiction just as soon as that decision is rendered. Gary Kurtz, in contrast, thinks that the "rule" which Abelleira enunciates is something entirely different, something neither enunciated nor hinted at in the fuller quotation immediately above, nor anywhere else in Abelleira � namely, Gary Kurtz thinks that the "rule" which Abelleira enunciates is that the Superior Court is powerless to examine its own in personam jurisdiction on its own motion.

Abelleira does touch on the issue of personal jurisdiction, but only in an introductory, wide-ranging discussion of the varieties of jurisdiction, and only to affirm the absence of reason to distinguish personal jurisdiction from other varieties:

Lack of jurisdiction in its most fundamental sense means an entire absence of power to hear or determine the case, an absence of authority over the subject matter or the parties. [Citation] Familiar to all lawyers are such examples as these: [...] A court has no jurisdiction to adjudicate upon the marital status of persons when neither is domiciled within the state.

|

Gary Kurtz's egregious misrepresentation of Abelleira further reinforces the impression that he practices law without scruple, and that he stages sham litigation without inhibition.

Court Spoliation Flashes a Green Light at Gary Kurtz Incorrigibility

In his most recent submission, Gary Kurtz tells the Superior Court that:

[A] defendant in default does not have the right to bring any motion other than a motion to set aside the default. See Devlin v. Kearney Mesa AMC/Jeep/Renault, Inc., 155 Cal.App. 3d 381, 385, 202 Cal.Rptr. 204 (1984).

|

What is galling about the Gary Kurtz statement above is certainly not its two typographical errors, and not even its being fallacious. What is galling is its demonstration of Gary Kurtz incorrigibility. In fact, Gary Kurtz is here parading his misunderstanding of Devlin v Kearny Mesa for the third time, each time putting Lubomyr Prytulak to the trouble of correcting him, the three cycles of Gary Kurtz misunderstanding (in red) followed by Lubomyr Prytulak correction (in blue) repeating as follows:

To reduce to a bare minimum Lubomyr Prytulak's third refutation of the Gary Kurtz third demonstration of his lack of understanding of Devlin v Kearny Mesa, it is sufficient to point out that Devlin v Kearny Mesa permits what Gary Kurtz insists is impermissible � which is to say, Devlin v Kearny Mesa bundles quashing service with vacating default, with the approval of both trial and appellate courts, just as happened in Pavlovich. Whether the courts either granted or denied the bundled motions is irrelevant to the question before the instant Superior Court of whether bundling was permitted � in Pavlovich, the motion to quash was initially denied, and later granted; in Devlin, the motion to quash was denied. One way or the other, though, bundling was permitted in both cases, and the central issue became quashing service on the ground of lack of jurisdiction, with vacating default playing the subordinate role of logical consequence. With regard to Devlin, the Kurtz-impermissible being permitted is captured in the single sentence:

We rejected Kearny Mesa's procedural arguments and affirmed the orders denying its motions to quash service of process and to set aside its default and default judgment.

|

Time would be saved, and the education of Gary Kurtz would be advanced, if the Los Angeles Superior Court had not fallen into the habit of spoliating Lubomyr Prytulak submissions, as Gary Kurtz might not then have been emboldened to ignore the copies with which he had been served, and he might not then have engaged as often in the mindless recitation of that which he had been shown to be false.

Defendant Lubomyr Prytulak's Case Has Been Made

What a consideration of the more salient of Gary Kurtz arguments above reveals is not that he is sometimes or often in error, but that he appears to have approached the asymptote of being always in error, of wildly guessing what his citations mean rather than imposing upon himself the discipline of reading them and faithfully reporting what they do mean. Lubomyr Prytulak lacks the resources to go through Rambam-Opposition-07-Jan-2003 and dissect every one of the remaining Gary Kurtz confusions and deceptions, and sees that more of them than have been discussed above are repetitions of mistakes that he has already made earlier and that Lubomyr Prytulak has already refuted. In any case, Lubomyr Prytulak estimates that a comprehensive reply would necessitate the instant Prytulak-to-Dunn-01 letter to be doubled in length, and so for that reason alone rests the remainder of his case upon the authority already amply cited in earlier Prytulak submissions, the one filed along with the many spoliated.

Spoliated Submissions Can be Redeemed Upon Appeal

The Lubomyr Prytulak trepidation that documents spoliated by the Los Angeles Superior Court would be barred from submission to the California Court of Appeal may have been needless, as the Appellate Rules within the 2003 California Rules of Court appear to have made provision for the redemption of documents that have been lodged with an inferior court, even when they have not been filed, and appear perhaps even to have made provision for the redemption of spoliated documents generally whether these meet the formal definition of having been "lodged" or not:

Rule 12. Augmenting and correcting the record |

Therefore, Lubomyr Prytulak has reason to hope that all spoliated documents will be restored upon appeal, and that these restored documents might � wherever relevant � persuade the appellate court of the bias of the Los Angeles Superior Court against Lubomyr Prytulak, and of the error of the Superior Court having denied Lubomyr Prytulak customary and obligatory clerical feedback, and of the error of the Superior Court having replied to numerous Lubomyr Prytulak questions with an impenetrable and inscrutable silence, and of the error of the Superior Court having overbilled Lubomyr Prytulak, and of the error of the Superior Court having failed to explain or make good the loss of two Lubomyr Prytulak money orders, and of the error of the Superior Court having failed to evaluate its personal jurisdiction in limine, and of the error of the Superior Court having spoliated most Lubomyr Prytulak submissions, and of the reality that all James R. Dunn proceedings have been nullities ab initio. Much dissatisfaction would have to be felt toward James R. Dunn for increasing the cost of justice, and delaying its arrival, by necessitating the creation of numerous documents which without his mismanagement would not have been needed � as for example the present letter � and after that obligating a higher court to read the proliferation of documents where he would not.

The alternative eventuality of the instant Superior Court failing to restore all spoliated documents, but nevertheless deciding that it lacks personal jurisdiction over Lubomyr Prytulak, would leave Lubomyr Prytulak with no occasion for, and therefore no possibility of, appeal; and would thus leave his spoliated documents unexhumed and unread; and would thus deprive Lubomyr Prytulak of the opportunity to ask a higher authority to evaluate important conclusions concerning Superior Court misconduct and error; and would thus also deprive the Superior Court of valuable direction from above which might assist it in improving its performance.

To ensure that none involved will be able to plead ignorance of the Prytulak accusation that documents have been spoliated, or plead ignorance of what these documents are, or ignorance that Lubomyr Prytulak requests them to be included in the trial record, here again is that list of eight spoliated documents that Prytulak requests be admitted to the trial record, seven of them Defendant Lubomyr Prytulak's, and one of them Plaintiff Steven Rambam's which happens to be helpful to the defense. Prytulak-Reply-D3 is rendered in bold because it is the most important of the spoliated documents, and its spoliation is the most prejudicial:

Motion-to-Quash-B dated 27-May-2002

www.ukar.org/temp/quash02.html

Prytulak-Query-B dated 14-Jun-2002

www.ukar.org/temp/query01.html

Motion-to-Quash-C dated 29-Aug-2002, accompanied by a money order for US$193

www.ukar.org/temp/quash03.html

Rambam-Objection-C dated 03-Sep-2002

www.ukar.org/temp/obj03sep.html

Prytulak-Reply-C dated 13-Sep-2002, accompanied by a money order for US$23

www.ukar.org/temp/rep13sep.html

Prytulak-Reply-D3 dated 05-Nov-2002

Prytulak-Reply-D7 dated 21-Nov-2002

www.ukar.org/temp/rep21nov.html

Prytulak-Request-For-Minute-Order dated 02-Dec-2002

www.ukar.org/temp/rep02dec.html

Two recently-submitted Prytulak documents present the Los Angeles Superior Court with the opportunity to raise the number of spoliated documents to ten:

Prytulak-to-Clark-03 Transcript Order dated 10-Jan-2003

www.ukar.org/temp/clarke01.html

Prytulak-to-Dunn-01 Three Documents Call for a Reply dated 20-Jan-2003 � the instant document

www.ukar.org/temp/dunn01.html

What Does Defendant Lubomyr Prytulak Mean by "Court"?

As Lubomyr Prytulak construes the James R. Dunn proceedings as being coram non judice, his references above to the instant "Court" must be understood not as Lubomyr Prytulak recognizing the judicial authority of the instant proceedings, nor as his attorning to Los Angeles Superior Court jurisdiction, but only as a shorthand for the more accurate, but unwieldy, "James R. Dunn coram non judice proceedings." Lubomyr Prytulak does not admit that the instant proceedings do really constitute a "Court," but refers to them as such only to achieve compactness of expression.

Lubomyr Prytulak

cc:

James A Bascue, Presiding Judge • LASC • 111 North Hill Street • Los Angeles, CA • USA 90012

John A Clarke, Executive Officer/Clerk • LASC • PO Box 151, Main Post Office • Los Angeles, CA • USA 90053

Robert A Dukes, Assistant Presiding Judge • LASC • 111 North Hill Street • Los Angeles, CA • USA 90012

Gary Klausner, Judge • USDC • 255 East Temple Street • Los Angeles, CA • USA 90012

Carolyn B Kuhl, Supervising Judge, Civil Departments • LASC • 111 North Hill Street • Los Angeles, CA • USA 90012

Gary Kurtz, Esq • 20335 Ventura Boulevard, Suite 200 • Woodland Hills, CA • USA 91364

S James Otero, Assistant Supervising Judge • LASC • 111 North Hill Street • Los Angeles, CA • USA 90012

Barry A Taylor, Judge • LASC • 6230 Sylmar Avenue • Van Nuys, CA • USA 91401

HOME DISINFORMATION PEOPLE RAMBAM KLAUSNER DUNN KUHL DUKES L.A. JUSTICE