|

Steven RAMBAM Plaintiff vs Lubomyr PRYTULAK Defendant |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Case No. BC 271433

DEFENDANT PRYTULAK ANSWER

[Not a general appearance CCP �418.10]

|

||

|

| ||||

|

Whenever the absence of jurisdiction of a proceeding is brought to the notice of a court, cognizance of the fact must be taken and the matter determined before it can move a further step in the case. • Marcil v. A. H. Merriman & Sons, Inc., 163 A 411 at 412 (Connecticut 1932) |

|

"Common sense indeed teaches that a question so vital as that of jurisdiction should be decided preliminarily to all others. Accordingly all treatises on pleading direct that pleas to the jurisdiction are to be filed first. Such, manifestly, is the natural order of pleading, for if any other plea be filed, the jurisdiction of the court is admitted. If the want of jurisdiction appears on the record, no plea need be interposed. The court, when the fact is brought to its notice, by motion or otherwise, in any stage of the case, will take proper action, and strike the case from the docket. If the want of jurisdiction does not appear on the record, and the parties appear and go to trial on the merits, it is matter of discretion with the court, whether, on suggestion of facts going to show a want of jurisdiction, the trial on the merits shall or shall not be suspended, and the evidence shall or shall not be heard." The court then went on to say: "If the information does not come early, it must not be rejected if it comes late. Whenever and however it comes, it should be received as the suggestion of an amicus curiae, and the proper legal action promptly taken." • Palmer v Reeves, 182 A 138 at 141 (Connecticut 1935) quoting Olmstead's Appeal, 43 Conn 110 at 112 (Connecticut) |

|

It is necessary for the jurisdictional facts to appear in the record; but the language in which such recitals are made need not be such as a skillful lawyer would use. • Pettibone v Wells, 179 So 336 at 339 (Mississippi 1938) |

|

The papers filed in the case and upon which the issues were made up, while somewhat informal perhaps, seem to have been amply sufficient to have apprised the court and all parties concerned exactly what should be decided, and we have had no difficulty in ascertaining the points for review in this court. All the district courts of this State, even in civil actions, frequently try and dispose of issues satisfactorily on papers far more informal than those at bar. The records in cases examined here abundantly establish that to be a fact. Besides it is axiomatic that every court has judicial power to hear and determine the question of its own jurisdiction of the parties and subject matter in a cause and it is necessarily required to do so when it undertakes its disposition. • Fox Park Timber Co. v Baker, 84 P2d 736 at 742 (Wyoming 1938) |

|

If a court finds at any stage of the proceedings, that it is without jurisdiction, it is its duty to take proper notice of the defect, and stay, quash or dismiss the suit. "This is necessary, to prevent the court from being forced into an act of usurpation, and compelled to give a void judgment. * * * So, ex necessitate, the court may, on plea, suggestion, motion, or ex mero motu, where the defect of jurisdiction is apparent, stop the proceeding." Branch v. Houston, 44 N.C. 85. • In re Davis' Custody, 103 SE2d 503 at 506-507 (North Carolina 1958). Citations omitted. The Branch v Houston "ex necessitate" statement above can be found widely quoted, as in: • Henderson County v Smyth, 5 SE2d 136 at 138 (North Carolina 1939) • Burgess v Gibbs, 137 SE2d 806 at 808 (North Carolina 1964) • Morgan v Hays, 426 P2d 647 at 650 (Arizona 1967) |

|

Lack of jurisdiction, however, may be raised at any time and not necessarily through the formality of a motion to erase, for the question, once raised, must be disposed of no matter in what form it is presented. • Carten v. Carten, 219 A2d 711 at 715 (Connecticut 1966). Other Connecticut decisions rely on almost identical wording: • Watson v Howard, 86 A2d 67 at 68 (Connecticut 1952) • Browning v. Steers, 295 A2d 544 at 545 (Connecticut 1972) • Castro v Viera, 541 A2d 1216 at 1220-1221 (Connecticut 1988) |

|

Every court has inherent power to determine whether it has jurisdiction over the subject matter of the proceedings before it. It makes no difference how the question comes to its attention. Once raised, the question must be disposed of, no matter in what manner of form or stage presented. The court on its own motion will examine grounds of its jurisdiction before proceeding further. • Carmichael v Iowa State Highway Com., 156 NW2d 332 at 340 (Iowa 1968) |

|

Every court has judicial power to hear and determine, or inquire into, the question of its own jurisdiction, both as to parties and as to subject matter, and to decide all questions, whether of law or fact, the decision of which is necessary to determine the question of jurisdiction. The court necessarily decides that it has jurisdiction by proceeding in the cause. When at any time or in any manner it is represented to the court that it has not jurisdiction, the court should examine the grounds of its jurisdiction before proceeding further, the question of jurisdiction being always open for determination. • 21 CJS Courts § 88 (1990) |

|

In 1 Black on Judgments, the author, discussing the opening and vacating of judgments by default, at section 94, says: "A judgment taken against a defendant by default will be opened or set aside on his motion, in the court wherein it was entered, for a failure of jurisdiction, or for certain classes of errors and irregularities." • Brame v Nolen, 124 SE 299 at 301 (Virginia 1924). Bold emphasis added. |

|

[T]he rule, springing from the nature and limits of the judicial power of the United States, is inflexible and without exception, which requires this court, of its own motion, to deny its own jurisdiction and, in the exercise of its appellate power, that of all other courts of the United States, in all cases where such jurisdiction does not affirmatively appear in the record on which, in the exercise of that power, it is called to act. On every writ of error or appeal, the first and fundamental question is that of jurisdiction, first, of this court, and then of the court from which the record comes. This question the court is bound to ask and answer for itself, even when not otherwise suggested and without respect to the relation of the parties to it. [...] The true question is, not what either of the parties may be allowed to do, but whether this court will affirm or reverse a judgment of the Circuit Court on the merits, when it appears on the record, by a plea to a jurisdiction, that it is a case to which the judicial power of the United States does not extend. The course of the court is, when no motion is made by either party, on its own motion, to reverse such a judgment for want of jurisdiction, not only in cases where it is shown, negatively, by a plea to the jurisdiction, that jurisdiction does not exist, but even when it does not appear, affirmatively, that it does exist. It acts upon the principle that the judicial power of the United States must not be exerted in a case to which it does not extend, even if both parties desire to have it exerted. I consider, therefore, that when there was a plea to the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court in a case brought here by a writ of error, the first duty of this court is, sua sponte, if not moved to it by either party, to examine the sufficiency of that plea and thus to take care that neither the Circuit Court nor this court shall use the judicial power of the United States in a case to which the Constitution and laws of the United States have not extended that power." • Mansfield, Coldwater & Lake Michigan Railroad Co. v Swan, 28 L Ed 462 at 464 (1884). Citations omitted. |

|

"It must always be ex officio the duty of every court to disclaim a jurisdiction which it is not entitled to exercise. To do otherwise would be to usurp a power not confided by the law." • Hanger v Commonwealth, 60 SE 67 at 68 (Virginia 1908) |

|

It is the duty of the court in all cases to examine of its own motion its jurisdiction to entertain a cause, even though not raised or argued. • Bar Ass'n of City of Boston v. Casey, 116 NE 541 at 543 (Massachusetts 1917). |

|

[I]t is the duty of the court to consider whether it has jurisdiction at whatever stage the objection may be presented, or of its own motion if not raised by a party. • Shannon v Shepard Mfg. Co., 119 NE 768 at 770 (Massachusetts 1918) |

|

Wherever a defect in the proceedings fatal to its jurisdiction is brought to the attention of the court, it must be considered; and the court does not wait for the parties to object, but acts of its own motion. • Town of Barton v Town of Sutton, 106 A 583 at 584 (Vermont 1919) |

|

A question of jurisdiction may be raised at any stage of the case, and such may be considered by the court sua sponte. • Dahlin v Missouri Commission for the Blind, 262 SW 420 at 421 (Missouri 1924) |

|

The rule, springing from the nature and limits of the judicial power of the United States, is inflexible and without exception, which requires this court, of its own motion, to deny its own jurisdiction and, in the exercise of its appellate power, that of all other courts of the United States, in all cases where such jurisdiction does not affirmatively appear in the record on which, in the exercise of that power, it is called to act. On every writ of error or appeal, the first and fundamental question is that of jurisdiction, first, of this court, and then of the court from which the record comes. This question the court is bound to ask and answer for itself, even when not otherwise suggested and without respect to the relation of the parties to it." • Hamilton v Browder, 54 P2d 1025 at 1027 (Oklahoma 1936) |

|

It is elementary that it is the duty of a court to refuse to entertain jurisdiction of a cause when it becomes apparent that it does not have jurisdiction. There was no error in the action of the trial court in dismissing the cause of action of the appellant on the court's own motion. • Fenstermacher v Indianapolis Times Pub. Co., 1 NE2d 655 at 657 (Indiana 1936). Citations omitted. |

|

We observe first that when any court is asked to exercise a power, its first duty is to determine whether that power has been conferred upon it, and this duty rests upon it whether its power is challenged or not. • Ryan v Kroger Grocery & Baking Co., 11 NE2d 204 at 206 (Ohio 1937) |

|

"Courts are bound to take notice of the limits of their authority, and accordingly a court may of its own motion, even though the question is not raised by the pleadings or is not suggested by counsel, recognize the want of jurisdiction, and it is its duty to act accordingly by staying proceedings, dismissing the action, or otherwise noticing the defect, at any stage of the proceedings." • Hutchins v Hutchins, 4 A2d 679 at 679 (Maine 1939). Citations omitted. |

|

It has long been the established law in this state that in adjudicating questions of jurisdiction, courts are not bound by the allegations of the plaintiff's petition. The rule is that, in the trial of a case, if at any time during its progress it becomes apparent that the court has no authority under the law to adjudicate the issues presented, it becomes the duty of the court to dismiss it. Under our system of jurisprudence the rule could not be otherwise because the judgment rendered by a court in a controversy over which the court does not have jurisdiction is a nullity. • Galley v Hedrick, 127 SW2d 978 at 980-981 (Texas 1939) |

|

That it is the duty of this court to inquire into its own jurisdiction, as well as the jurisdiction of the court from which the appeal is taken, whether presented by the parties or not, is too thoroughly settled to require any extensive discussion or citation of authorities. • Harber v McKeown, 157 P2d 753 at 754 (Oklahoma 1945) |

|

The question of jurisdiction should be inquired into by the court at the earliest inception on its own initiative to ascertain whether or not it has jurisdiction. • Sheridan County Electric Co-Op., Inc. v Anhalt, 257 P2d 889 at 889-890 (Montana 1953) |

|

It is a well established principle of law that a court lacks power to hear or determine a case concerning subject matters over which it has no jurisdiction. Furthermore a court has the power to examine and determine on its own motion whether it has jurisdiction of a matter presented to it. • Appeal of Matheisel, 224 A2d 832 at 832 (New Hampshire 1966). Citations omitted. |

|

It is inherently within the power and duty of the Court of general jurisdiction to determine its jurisdiction. • Niles v Marine Colloids, Inc., 249 A2d 277 at 279 (Maine 1969) |

|

When jurisdiction is not properly invoked, the trial court is without authority to render a judgment. The jurisdiction of the court may be raised at any time by motion or by the court. • Troutman v Mitchem, 472 NE2d 69 at 71, (Ohio 1984). Citations omitted. |

|

While the court may raise issues on its own motions, it is limited to issues of jurisdiction. • Frontier Ditch Co. v Chief Engineer of Div. of Water Resources, 704 P2d 12 at 17 (Kansas 1985) |

|

The court has a duty to sua sponte inquire into and determine whether it has jurisdiction. • In Interest of D.L.D., 701 SW2d 152 at 156 (Missouri 1985) |

|

A court is bound to take notice of the limits of its jurisdiction even though the question is not raised. • Paulson v Secretary of State, 398 NW2d 477 at 480 (Michigan 1987) |

|

A court must notice, even sua sponte, the matter of its own jurisdiction, for jurisdiction is fundamental in nature and may not be ignored. • K & S Interests, Inc. v Texas American Bank/Dallas, 749 SW2d 887 at 890 (Texas 1988) |

|

A court has the power and duty to examine and determine whether it has jurisdiction of a matter presented to it, its determination being subject, of course, to appellate review. This question should be considered by the court before it looks at other matters involved in the case, such as whether the parties are entitled to a jury trial. It may, and must, do this on its own motion, without waiting for the question of its jurisdiction to be raised by any of the parties involved in the proceeding. • 20 Am Jur 2d § 60 (1995) |

|

Where the record fails affirmatively to show jurisdiction of the person of the defendant, a judgment by default, on direct appeal, is fundamentally erroneous. • Peterson & Tvrdik v Mueller-Huber Grain Co., 58 SW2d 890 at 892 (Texas 1933) |

|

But in all the cases it has been distinctly made a condition of immunity of judicial officers from damage for wrong and injury done by his decision or act that such decision be rendered or act done within his jurisdiction of the subject matter or of the person affected. As said in Cooley, Torts, 416: "Every judicial officer, whether the grade be high or low, must take care, before acting, to inform himself whether the circumstances justify his exercise of the judicial function. A judge is not such at all times, and for all purposes. When he acts, he must be clothed with jurisdiction, and, acting without this, he is but the individual assuming an authority he does not possess." • Glazar v. Hubbard, 42 SW 1114 at 1115 (Kentucky 1897). The Cooley statement above is quoted with approval in • Blincoe v Head, 44 SW 374 at 375 (Kentucky 1898), though without the introductory acknowledgement that it applies to both subject matter jurisdiction and personal jurisdiction. |

|

A judgment, order or decree entered by a court which lacks jurisdiction of the parties or of the subject matter, or which lacks the inherent power to make or enter the particular order involved, is void, and may be attacked at any time or in any court, either directly or collaterally. • Barnard v Michael, 63 NE2d 858 at 861-862 (Illinois 1945). Bold emphasis added. The exact same statement is quoted with approval thirty-one years later in • City of Chicago v Fair Employment Practices Commission, 357 NE2d 1154 at 1155 (Illinois 1976) |

|

But the presumptions which the law implies in support of the judgments of superior courts of general jurisdiction, only arise with respect to jurisdictional facts concerning which the record is silent. Presumptions are only indulged to supply the absence of evidence or averments respecting the facts presumed. They have no place for consideration when the evidence is disclosed or the averment is made. When, therefore, the record states the evidence or makes an averment with reference to a jurisdictional fact, it will be understood to speak the truth on that point, and it will not be presumed that there was other or different evidence respecting the fact, or that the fact was otherwise than as averred. [...] Whenever, therefore, it appears from the inspection of the record of a Court of general jurisdiction that a defendant against whom a personal judgment or decree is rendered was, at the time of the alleged service, without the territorial limits of the Court, and thus beyond the reach of its process, and that he never appeared in the action, the presumption of jurisdiction over his person ceases, and the burden of establishing the jurisdiction is cast upon the party who invokes the benefit or protection of the judgment or decree. This is so obvious a principle, and its observance is so essential to the protection of parties without the territorial jurisdiction of a court, that we should not have felt disposed to dwell upon it at any length, had it not been impugned and denied by the circuit court. • Mr. Justice Field in Galpin v Page, 21 L Ed 959 at 963 (1873). Also quoted with approval in • Laughlin v Hughes, 89 P2d 568 at 573 (Oregon 1939). The same is expressed also in • Hill v Daley, 328 NE2d 142 at 145 (Illinois 1975). |

|

"Where a court of general jurisdiction proceeds to adjudicate a cause there is a presumption of jurisdiction; but this presumption applies only when the record is silent upon the question, and if there is an affirmative showing in the record that there was no jurisdiction the judgment or decree will be void." • Forrest v Fey, 75 NE 789 at 791 (1905) as quoted in Evans v Advance Schools, Inc., 388 NE2d 1003 at 1005 (Illinois 1979) |

|

Both jurisdiction of the person and jurisdiction of the subject matter must concur or the judgment will be void in any case in which the court has assumed to act, and it is therefore fundamental that subject matter or personal jurisdiction can be raised at any time either directly or collaterally. • Sullivan v Bach, 427 NE2d 645 at 650 (Illinois 1981) |

|

Every judgment of a court rendered without jurisdiction is a nullity � not merely viodable but void � and may be disregarded. It is subject to attack by any person at any time in any court and in any proceeding in which it is brought in question. • People v Miller, 171 NE 672 at 675 (Illinois 1930). |

|

It is a rule well established that a void judgment or order may be vacated at any time and the doctrines of laches and estoppel do not apply. • Thayer v Lillage of Downers Grove, 16 NE2d 717 at 719 (Illinois 1938). |

|

Two exceptions to the rule that a judgment cannot be assailed after the expiration of the time for appeal or suing out of a writ of error are, first, where the court was without jurisdiction to render the judgment entered and, second, where the judgment was obtained by fraud. [...] Again, a void judgment or order may be vacated at any time and the doctrines of laches and estoppel do not apply. • Ward v Sampson, 70 NE2d 324 at 327 (Illinois 1946). |

|

Where the right of a court to take jurisdiction of a given case is dependent on a given fact, the determination of that fact, like any other question of fact, is referred in the first instance to the trial court. It is a fact which that court must determine in limine in every case. • State v Kauffman, 149 P 656 at 657 (Washington 1915). Also quoted with approval in • Pfirman v Probate Court of Shoshone County, 64 P2d 849 at 851 (Idaho 1937) |

|

Neither party has questioned our jurisdiction, but the first question to be decided by any court in any case is whether or not it has jurisdiction in point of fact. It is as essential to the orderly administration of justice that we should decline to proceed in any case where jurisdiction is absent, as that we should unhesitatingly adjudicate when jurisdiction appears. • Bealmer v. Harford Fire Ins. Co., 220 SW 954 at 956 (Missouri 1920) |

|

It is a matter of first consideration of any court to determine its own jurisdiction of a case, and, if lack of jurisdiction appears, as a matter of law, the court should dismiss the case without passing upon any other issue presented, whether of law or fact. • Lone Star Finance Corporation v Davis, 77 SW2d 711 at 714 (Texas 1934) |

|

We observe first that when any court is asked to exercise a power, its first duty is to determine whether that power has been conferred upon it, and this duty rests upon it whether its power is challenged or not. • Ryan v Kroger Grocery & Baking Co., 11 NE2d 204 at 206 (Ohio 1937) |

|

The decision of the question of whether the court has jurisdiction is a preliminary one to the determination of the merits of the cause, and is for the court to decide. • Bridges v Wyandotte Worsted Co., 132 SE2d 18 at 22 (South Carolina 1963) |

|

The trial court must try the jurisdictional issue before addressing issues on the merits. Henderson v Milex Products, Inc., 370 NW2d 291 at 292 (Wisconsin 1985) |

|

In every case, a threshold inquiry must be made to determine whether a court has proper jurisdiction over the claim before it. • Levinson v American Accident Reinsurance Group, 503 A2d 632 at 634 (Delaware 1985) |

|

The jurisdiction of the lower court depends upon the state of things existing at the time the suit was brought. • Minneapolis & St. Louis Railroad Co. v Peoria & Pekin Union Railway Co., 270 US 580 at 586 (U.S. 1926) |

|

Moreover, to perfect service pursuant to the long-arm statutes, the complaint must allege the jurisdictional requirements prescribed by the statutes. [...] Failure to adequately allege the basis for invoking long-arm jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant voids any service of process. • City Contract Bus Service, Inc. v Woody, 515 So2d 1354 at 1356 (Florida 1987) |

|

The statutory proceedings noted, and to which the law exacts a close adherence, are all steps necessary to be successively taken in order to show the court's jurisdiction over the defendant, and in cases of judgment by default such jurisdiction must affirmatively appear. • Friend v Thomas, 187 SW 986 at 987-988 (Texas 1916) |

|

Where the record fails affirmatively to show jurisdiction of the person of the defendant, a judgment by default, on direct appeal, is fundamentally erroneous. • Peterson & Tvrdik v Mueller-Huber Grain Co., 58 SW2d 890 at 892 (Texas 1933). Also cited with approval in • Reynolds v Volunteer State Life Ins. Co., 80 SW2d 1087 at 1093 (Texas 1935) |

|

[W]e hold that a special appearance and motion to quash the service of summons is an answer within the meaning of C.S. � 6832, that during the pendancy of such motion the defendant is not in default, and that the trial court abused its discretion in this case in refusing to set aside the default and judgment upon appellant's motion. • Central Deep Creek Orchard Co. v Taft, 202 P 1062 at 1065 (Idaho 1921). Also favorably quoted in • In re Smith, 225 P 495 at 496 (Idaho 1924) |

|

A "judgment by default" is one taken against a defendant who has been duly summoned or cited in an action and has failed to appear. The distinguishing feature of a default judgment is that it follows from the omission of a defendant to appear. The rule is firmly established that when an answer or other pleading of a defendant has raised an issue of law or fact, a judgment by default cannot be entered against him. [...] If the motion to dismiss raised a question of law, then appellant was entitled to have such issue disposed of before a default judgment could be entered against it. This special appearance stayed the time for filing a pleading that tendered an issue as prescribed by C. S. § 4102, until such a time as this motion had been disposed of, and default could not be taken while the issue it tendered had not been disposed of. • In re Smith, 225 P 495 at 496 (Idaho 1924) |

|

While ordinarily presumptions are made in support of a judgment (including presumptions of due service of citation when the judgment so recites), no such presumptions are made in a direct attack upon a default judgment. We think the same rule would apply to inferences of jurisdictional facts in a direct attack. As noted above, jurisdiction in this type of case must affirmatively appear on the face of the record. The provisions of Article 2031b are clear, and plaintiff has the burden of making sufficient allegations to bring the defendant within its provisions. • McKanna v Edgar, 388 SW2d 927 at 929-930 (Texas 1965). Citations omitted. |

|

Unless the default is set aside after a duly noticed motion which complies with all legal requirements, this case will proceed to the trial setting hearing and default prove-up hearing as described above. • Los Angeles Superior Court "Minute Order" of 15-Aug-2002, p. 3. |

|

Future Hearings 11/25/2002 at 08:35 am in department 26 at 111 North Hill Street, Los Angeles Motion Set Aside Default/Judgment • Los Angeles Superior Court web site Case Summary for Case BC271433 at www.lasuperiorcourt.org/civilCaseSummary/index.asp?CaseType=Civil |

|

The only motion this Court may hear is a motion to set aside default, not a jurisdictional motion. [...] [D]efendant has forfeited his right to bring a motion to quash. [...] A motion to quash would not be timely. [...] Accordingly, defendant is not at liberty to file a motion to quash. • Gary Kurtz, Rambam-Objection-C, 03-Sep-2002, pp. 2-3. |

|

At that point, defendant had forfeited his right to bring a motion to quash. See Devlin v. Kearney Mesa AMC/Jeep/Renault, Inc., 155 Cal.App.3d 381, 385, 202 Cal.Rptr. 204 (1984). Moreover, a motion to quash would not have been timely. • Gary Kurtz, Rambam-Objection-D1 on 30-Sep-2002 (p. 4). Italicization of "See" is in the original, as is the misspelling of "Kearny" as "Kearney." |

|

Plaintiff particularly objects to the constant recitation of jurisdictional arguments. Defendant has filed a motion to set aside the default based entirely on his jurisdictional arguments. Plaintiff will respond, at an appropriate time. Plaintiff could, if necessary, respond to the jurisdictional arguments. Plaintiff could, if necessary, outline his substantial ties to California. Further, plaintiff could present arguments regarding defendant's claimed lack of contacts. Plaintiff has refrained from those arguments because they are not presently relevant. Jurisdictional arguments are not appropriately made in letter form. Moreover, jurisdictional arguments are not ripe while a default is in place. They may be raised within the time to plead and before the entry of a default, or they may be raised if the default is set aside and if leave is granted. • Gary Kurtz, Rambam-Objection-D2, 10-Oct-2002, p. 2. Bold emphasis was in the original; paragraph numbering omitted. |

|

The entry of a default terminates a defendant's rights to take any further affirmative steps in the litigation until either its default is set aside or a default judgment is entered. • Devlin v Kearny Mesa AMC/Jeep/Renault, Inc., 202 Cal Rptr 204 at 206-207 (California 1984) |

|

Our first decision rightly assumed Kearny Mesa, having defaulted, knew it could not participate in a judgment hearing on punitive damages. The entry of a default terminates a defendant's rights to take any further affirmative steps in the litigation until either its default is set aside or a default judgment is entered. • Devlin v Kearny Mesa AMC/Jeep/Renault, Inc., 202 Cal Rptr 204 at 206-207 (California 1984). Bold emphasis added. |

|

We rejected Kearny Mesa's procedural arguments and affirmed the orders denying its motions to quash service of process and to set aside its default and default judgment. • Devlin v Kearny Mesa AMC/Jeep/Renault, Inc., 202 Cal Rptr 204 at 205-206 (California 1984). Bold emphasis added. |

|

At that point, defendant had forfeited his right to bring a motion to quash. See Devlin v. Kearney Mesa AMC/Jeep/Renault, Inc., 155 Cal.App.3d 381, 385, 202 Cal.Rptr. 204 (1984). • Gary Kurtz, Rambam-Objection-D1 of 30-Sep-2002 (p. 4). Italicization of "See" is in the original, as is the misspelling of "Kearny" as "Kearney." |

|

The distinction between an entry of default and a default judgment must here be recognized. Entry of default is normally a clerical act which may be performed by the clerk of court, and it does not constitute a judgment. The entry of default generally forecloses the party found to be in default from making any further defense or assertion with respect to liability or an asserted claim. Although the entry of default generally establishes the fact of liability according to the complaint, it does not establish either the amount or the degree of relief. The default judgment, on the other hand, in addition to the fact of liability, defines the amount of liability or the nature of the relief. This is generally done separately from the entry of default. • Spitzer v Spitzer, 777 P2d 587 at 592 (Wyoming 1989). Citations omitted, bold emphasis added. |

|

If it [default entry] were not a proceeding, or order, the party could not obtain relief from it at all under that section. It is not a judgment [one might fallaciously argue], and the section authorizes relief only from a judgment, order, or proceeding. The argument[, however,] is really self-destructive. If the default [entry] cannot be set aside, because it is not a proceeding or order, of what avail would it be to set aside the [ensuing default] judgment? The default [entry] would stand undisturbed. A default [entry] cuts off the defendant from making any further opposition or objection to the relief which plaintiff's complaint shows he is entitled to demand. A defendant against whom a default is entered "is out of court and is not entitled to take any further steps in the cause affecting plaintiff's right of action." 6 Ency. of Pl. & Pr. 126. He cannot thereafter, nor until such default is set aside in a proper proceeding, file pleadings, or move for a new trial, or demand notice of subsequent proceedings. Id., 127. "A default confesses all the material facts in the complaint." Rowe v. Table M. W. Co., 10 Cal. 441. Consequently, if the [default] judgment were vacated [but not the default entry], it would be the duty of the court immediately to render another [default judgment] of like effect, and the defaulting defendants would not be heard for the purpose of interposing any denial [of the allegations plaintiff makes within his complaint] or affirmative defense [against the allegations plaintiff makes within his complaint]. • Title Insurance & Trust Co. v King Land & Improvement Co., 120 P 1066 at 1067 (California 1912). Red insertions prevent the misinterpretation that the quotation above may be particularly prone to. |

|

Showing that plaintiff or his attorney before judgment said or did something which put defendant off guard or prevented him from defending, and that defendant had prima facie valid defense, is sufficient to warrant relief from default judgment for "fraud practiced by the successful party." [...] In deducing it from the statutory delimitation of the right to reopen a case, the word "fraud" is not confined to its vicious import of a wicked motive or deliberate deceit, or an affirmative evil act purposefully conceived, but is deemed sufficiently expansive to embrace merely leading astray, throwing off guard, or lulling to security and inaction, be the intention or motive good or bad, with a resultant advantage to the one and an apparent injustice to the other. So the law is declared to be that if before a judgment was rendered a party plaintiff or his attorney said or did anything that put his adversary off guard, or prevented him from defending the action, and he shows that he had a prima facie valid defense, he is entitled to relief from the judgment. This is on the idea that such conduct operated as a fraud upon his rights. There has been a firm adhesion to this precept. • Johnson v Gernert Bros. Lumber Co., 75 SW2d 357-358 (Kentucky 1934). Citations omitted; bold emphasis added. |

|

Two exceptions to the rule that a judgment cannot be assailed after the expiration of the time for appeal or suing out of a writ of error are, first, where the court was without jurisdiction to render the judgment entered and, second, where the judgment was obtained by fraud. [...] Again, a void judgment or order may be vacated at any time and the doctrines of laches and estoppel do not apply. • Ward v Sampson, 70 NE2d 324 at 327 (Illinois 1946) |

| CCP § 473(d) The court may, upon motion of the injured party, or its own motion, correct clerical mistakes in its judgment or orders as entered, so as to conform to the judgment or order directed, and may, on motion of either party after notice to the other party, set aside any void judgment or order. |

| Disambiguated CCP § 473(d) The court may, upon motion of any party, or upon its own motion, correct clerical mistakes or set aside any void judgment or order. |

|

In 1 Black on Judgments, the author, discussing the opening and vacating of judgments by default, at section 94, says: "A judgment taken against a defendant by default will be opened or set aside on his motion, in the court wherein it was entered, for a failure of jurisdiction, or for certain classes of errors and irregularities." • Brame v Nolen, 124 SE 299 at 301 (Virginia 1924) |

|

Our decision requires that the default judgments be set aside on the ground that the record fails to show that the district court acquired personal jurisdiction of the defendants. • Whitney v L & L Realty Corporation, 500 SW2d 94 at 97 (Texas 1973) |

|

We rejected Kearny Mesa's procedural arguments and affirmed the orders denying its motions to quash service of process and to set aside its default and default judgment. • Devlin v Kearny Mesa AMC/Jeep/Renault, Inc., 202 Cal Rptr 204 at 205-206 (California 1984) |

|

[T]he mere fact that the party has defaulted below does not defeat his right to appeal. He may, on direct appeal from the default judgment, attack it for want of jurisdiction in the court, or for failure of the complaint to state a claim, or for procedural irregularity in the course of the proceedings below. • Spitzer v Spitzer, 777 P2d 587 at 590 (Wyoming 1989). Italics removed from the original. |

|

We first address whether respondent could properly bring its petition to vacate the default judgment on jurisdictional grounds. [...] [A] void judgment, order or decree may be attacked at any time or in any court, either directly or collaterally. A court has inherent authority to expunge void acts from its records. A judgment or order is void where it is entered by a court which lacks jurisdiction over the parties or the subject matter, or lacks inherent power to enter the particular order or judgment, or where the order is procured by fraud. Where, as here, the petition sought to attack the [default] judgment on jurisdictional grounds, we find that respondent's petition was properly brought before the trial court. • Evans v Corporate Services 565 NE2d 724 at 727-728 (Illinois 1990). Citations omitted. |

|

[A]ppellant filed a single pleading containing a motion to quash service of process and a motion to vacate final [default] judgment. [...] We need not address appellant's argument on her motion to vacate the default judgment. • Montero v DuVal Federal Savings and Loan Association, 581 So2d 938 at 939-940 (Florida 1991) Why does the court decline to address the motion to vacate default? � Probably because there is no separate issue to address, default already having been automatically vacated by the successful quashing of service. |

|

On February 26, 1997, Floveyor specially appeared and filed a motion to set aside the default judgment and a motion to quash Shick's service of summons and the cross-complaint. • Floveyor International Ltd. v Superior Court 69 Cal Rptr 2d 457 at 459 (California 1997) |

|

"[C]ompliance with the statutory procedures for service of process is essential to establish personal jurisdiction. Thus, a default judgment entered against a defendant who was not served with a summons in the manner prescribed by statute is void. Under section 473, subdivision (d), the court may set aside a default judgment which is valid on its face, but void, as a matter of law, due to improper service. • Ellard v Conway, 114 Cal Rptr 2d 399 at 401 (California 2001). Citations omitted. |

|

"Common sense indeed teaches that a question so vital as that of jurisdiction should be decided preliminarily to all others. Accordingly all treatises on pleading direct that pleas to the jurisdiction are to be filed first. Such, manifestly, is the natural order of pleading, for if any other plea be filed, the jurisdiction of the court is admitted. • Palmer v Reeves, 182 A 138 at 141 (Connecticut 1935) quoting Olmstead's Appeal, 43 Conn 110 at 112 (Connecticut). Bold emphasis added. |

|

The District Court of Appeal, Dell, J., held that defendant did not waive her right to contest service of process by joining her motion to quash service of process with motion to vacate default judgment. • Montero v Duval Federal Savings and Loan Association, 581 So2d 938 at 938 (Florida 1991). Bold emphasis added. |

|

In Montero v Duval Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass'n, 581 So.2d 938, 939 (Fla. 4th DCA 1991), we held that a defendant did not submit himself to the jurisdiction of the court where he had filed a motion to quash service of process along with a motion to set aside a default. • Ginsberg v Lamour, 711 So2d 182 at 183 (Florida 1998). Bold emphasis added. |

|

Florida courts have repeatedly held that filing a motion to vacate a default does not waive

jurisdictional defenses where such defenses are raised simultaneously with the motion. • National Safety Associates, Inc. v Allstate Insurance Company (Florida 2001) at www.2dca.org/opinion/October%2005,%202001/2d01-374.pdf |

|

Defendant complains that the Court clerks failed to instruct him on how to properly file a motion. [...] In addition, the Court clerk acted properly by refusing to give legal advice. • Rambam-Objection-D1, p. 4. |

|

The "Motion" was not accompanied by a filing fee [required per Government Code §§26830, 68090.7, 72055 ff.]. The payment of filing fees is both mandatory and jurisdictional. See Hu v. Silgan Containers (1999) 70 CA4th 1261. Thus, the Court was without jurisdiction to consider the motion. • Los Angeles Superior Court "Minute Order" of 15-Aug-2002, p. 2. |

|

The Court of Appeal, Raye, J., held that trial court lacked jurisdiction to reinstate complaint once plaintiff failed to pay filing fee within 20 days after notice was mailed informing her that her check had been returned for insufficient funds. [...] On May 28, 1997, the superior court clerk notified Hu by certified mail the bank had returned her check for insufficient funds. The letter informed Hu that she was required to pay the fee and late charges within 20 days of the receipt of the letter. • Hu v Silgan Containers, 83 Cal Rptr 2d, 333 at 333-334 (California 1999) |

|

That official, noting that no fee had been forwarded with the notice [...] immediately mailed to counsel for appellant his invoice acknowledging receipt of the notice and requesting the filing fee. • Kientz v Harris, 257 P2d 41 at 42 (California 1953) |

|

On that day the appellants sent their notice of motion to the clerk, but the clerk did not file the same, because the fee therefor was not paid; and three days afterwards, at the request of the appellants, who then paid the fee, the clerk indorsed it as filed February 23d. • Davis v Hurgren, 57 P 684 at 685 (California 1899) |

|

Notice of Motion of the wife for a new trial was filed and served by mail on April 22, 1955, but the filing fee was not paid until April 29. • Foley v Foley, 304 P2d 719 at 719 (California 1956) |

|

Federal rules reject the approach that pleading is a game of skill in which one misstep by counsel may be decisive to the outcome and accept the principle that the purpose of pleading is to facilitate a proper decision on the merits. [...] The ends of justice are not served when forfeiture of just claims because of technical rules is allowed. [...] "Thus, the Travelers Insurance Company 'hid in the bushes' so to speak and finally struck the plaintiff from ambush." • Travellers Indemnity Co. v United States, 382 F2d 103 at 104, 106 (1967) |

| Defendant's letters are an improper ex-parte contact, which deprive plaintiff of a proper forum for objection, response, and hearing. |

| DATED: 05 November 2002 |

By: Lubomyr Prytulak Defendant |

| DOCUMENT NAME |

CASE | DATE | JUDGE |

FILING FEE |

COURT ACTION |

| Rambam-Complaint-A | 02E00326 | Date 04-Jan Filed 09-Jan |

Barry A. Taylor | Unknown | Filed 09-Jan |

| Motion-to-Quash-A | 02E00326 | Date & mail 03-Apr Filed 08-Apr |

Barry A. Taylor | None sent | Filed as "correspondence received" 08-Apr |

| Rambam-Complaint-B | BC271433 | Date 03-Apr Filed 04-Apr |

James R. Dunn | Unknown | Filed 04-Apr |

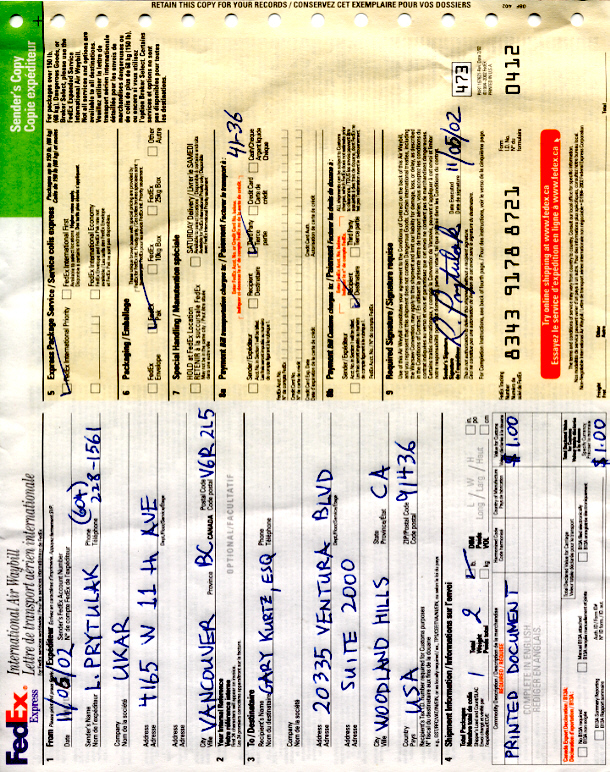

| Motion-to-Quash-B | BC271433 | Date 27-May Deliv FedEx 29-May |

James R. Dunn | None sent | Unfiled, though alluded to in "Minute Order" |

| Prytulak-Query-B | BC271433 | Date 14-Jun Deliv FedEx 17-Jun |

James R. Dunn | None sent | Unfiled |

| Motion-to-Quash-C | BC271433 | Date 29-Aug Deliv FedEx 30-Aug |

James R. Dunn | US$193 | Missing |

| Rambam-Objection-C | BC271433 | Date & mail 03-Sep Receive 09-Sep |

James R. Dunn | Unknown | Unfiled, possibly missing |

| Prytulak-Reply-C | BC271433 | Date 13-Sep Deliv FedEx 17-Sep |

James R. Dunn | US$23 | Missing |

| Motion-to-Quash-D | BC271433 | Date & Fax 25-Sep Deliv FedEx 26-Sep |

James R. Dunn | US$239 | Filed 26-Sep |

| Rambam-Objection-D1 | BC271433 | Date & mail 30-Sep Receive 04-Oct |

James R. Dunn | Unknown | Filed 01-Oct |

| Rambam-Objection-D2 | BC271433 | Date 10-Oct, mail 14 Receive 17-Oct |

James R. Dunn | Unknown | Filed 15-Oct |

| CCP �1016.6 (d) The copy of the notice or other paper served by Express Mail or another means of delivery providing for overnight delivery pursuant to this chapter shall bear a notation of the date and place of deposit or be accompanied by an unsigned copy of the affidavit or certificate of deposit. |

|

ATTORNEY OR PARTY WITHOUT ATTORNEY (Name and address):

TELEPHONE NO.:

Defendant without attorney is: Lubomyr Prytulak [Telephone] [Address] |

FOR COURT USE ONLY |

|

NAME OF COURT: Los Angeles Superior Court 111 North Hill Street Los Angeles, California USA 90012 |

|

PLAINTIFF/PETITIONER: Steven Rambam DEFENDANT/RESPONDENT: Lubomyr Prytulak |

|

| DECLARATION |

CASE NUMBER

BC271433 |