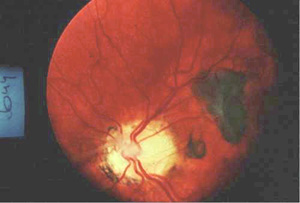

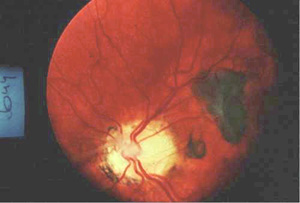

Toxocara canis � Retinal granuloma � damage done as a result of migrating larvae, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison www.vetmed.wisc.edu/pbs/vetpara/gallery.html

Toxocara canis � Retinal granuloma � damage done as a result of migrating larvae, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison www.vetmed.wisc.edu/pbs/vetpara/gallery.html

Toxocara canis � Retinal granuloma � damage done as a result of migrating larvae, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison www.vetmed.wisc.edu/pbs/vetpara/gallery.html

Toxocara canis � Retinal granuloma � damage done as a result of migrating larvae, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison www.vetmed.wisc.edu/pbs/vetpara/gallery.html

|

F. David Radler

F. David Radler

|

| 16-Sep-2001 |

|

Press suppression of the health hazards of Toxocara canis |

|

Worm in raccoons peril to humans A common intestinal worm in raccoons can infect people, sometimes with fatal results, the American Veterinary Medical Association has warned. The association's Council on Public Health and Regulatory Veterinary Medicine noted that the parasite, Baylisascaris procyonis, has recently caused fatal infections in two children, as well as in some species of wildlife. Adults can also be infected, resulting in damage to the eyes and other symptoms. The parasites are transmitted by the ingestion of eggs excreted by raccoons. The eggs may contaminate hands, objects or food that are put in the mouth. After ingestion, the eggs can hatch into larvae that migrate throughout the body, especially to the brain, eyes and spinal cord. � NYT Globe and Mail, 22-May-1984, p. 10. |

|

It may well be that toxoplasmosis is responsible for more social problems than is generally supposed. Amongst northern races, in particular, one of the great problems of the day is that of the backward or delinquent child. Many reasons are suggested for a child's failure to progress or to conform to the rules of the community, inherited stupidity, poor social background, problems of puberty, failure to integrate with other children. However, other causes are also being sought such as low grade lead or mercury intoxication, or else some chronic infectious condition. Of the latter, toxoplasmosis is perhaps the most probable [...].

Richard N. Fiennes. Zoonoses and the Origins and Ecology of Human Disease. New York: Academic Press, 1978, p. 119. |

|

It has been established that infection is acquired by ingesting soil previously contaminated by infected dogs. Eggs [...] taken into the intestine of a child, erupt from the egg, penetrate the intestinal wall, and soon reach the liver. A majority of the larvae may remain in the liver but others pass on to the lungs and to other parts of the body. Larvae have been found in nearly all organs. It is of chief interest that a high proportion of them invade the central nervous system and a considerable number have been found in the eye. The tragic consequences of invasion of the eye is the development of a lesion which by its resemblance to retinoblastoma prompts the unnecessary removal of that vital organ.

Beaver, P. C. Visceral and cutaneous larva migrans. Public Health Reports, 1959, 74, 328-332. |

|

Slitlamp examination [...] showed a worm in the left cornea, obviously a nematode larva. It had the external appearance of Toxocara [...]. The most startling observation in this case was the ease and rapidity with which the larva was able to move about in the cornea, one of the densest structures of the human body. Its movement was so rapid, in fact, that the surgeon's instruments, in spite of numerous attempts, never won the race. Baldone, J. A., Clark, W. B., & Jung, R. C. Nematode ophthalmitis. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 1964, 57, 763-766. |

|

Why should we have become interested in Toxocara canis and its near relative Toxocara cati? The answer is that a patient was admitted to the medical unit at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases with proved T. canis infection [...]. [...] In brief he was aged 5 and had had an eye removed for a suspected retinoblastoma. The tumour turned out to be a granuloma, and after considerable difficulty and after cutting some 100 sections a larva was found and identified as T. canis by Professor J. C. C. Buckley. The boy had never been away from Britain, and the question was therefore asked how he had become infected. [...] When infective T. canis or T. cati eggs are swallowed by man larvae emerge from the eggs in the human intestine, penetrate the bowel wall, and are taken in portal blood to the liver and the lungs and usually beyond them to other tissues throughout the body. Sprent (1995a) deduced that it is the size and shape of the body of the larva which determines the kind of vessel it enters and hence how it proceeds along its migratory pathway. Once in a vessel the larva appears to leave it at a point at which its body approaches the diameter of the vessel. This is indicated by the occurrence of haemorrhages at specific sites, such as those on the surface of the brain in mice experimentally infected with T. canis (Sprent, 1955b). This is also likely to explain the somewhat uniform position of granulomata caused by larvae of T. canis emerging from retinal blood vessels (Duguid, 1961a, 1961b). [...] In experimental animals the parasites become widely disseminated, and it appeared probable that this occurred in man. Moreover, as the eye is a small organ and yet most identified T. canis larvae have been found there, it would appear probable that for every case in which it was involved there would be several in which other tissues were invaded, but that invasion occurs with fewer symptoms than when the eye is affected. If sight is damaged a patient soon seeks medical help, but if larvae invade the liver, lung, or even the brain they are likely to give rise to symptoms the significance of which is difficult to assess. [...] Both in experimental animals and in man the second-stage larvae of T. canis and T. cati are known to wander widely in the tissues and to reach many organs, including the brain. As they burrow through the tissues they produce tracks in which there are haemorrhage, necrosis, and inflammatory cells. When they die and disintegrate they give rise to granulomatous foci. Knowing that the brain had been involved in man on at least one proved occasion the question was asked whether there were any diseases resulting from brain damage in which toxocaral invasion might play a part [...]. [...] There is also evidence that some cases of epilepsy almost certainly result from toxocaral invasion of the brain. This knowledge has therefore helped to recover from the many labelled as idiopathic some cases of epilepsy and some of hepatomegaly, asthma, and eosinophilia. [...] Because the larvae are small and because as few as 20 may cause significant illness or lesions it is certain that in most infected patients it will never be possible to diagnose the infection by recovering larvae. Even when the larvae are present in quite small lesions many serial sections may be necessary to locate one. Woodruff, A. W. Toxocariasis. British Medical Journal, 1970, 3, 663-669. |

|

The question arose as to why, in view of the obviously large reservoir of T. canis and T. cati and the close contacts of dogs and cats with man, so few human cases were reported. The reported cases appeared to be confined to those in which the loss of sight in an eye from larva migrans rendered the diagnosis unmistakeable; it was argued that, if the worm reached the eye in some cases, infection of other organs, such as liver, spleen or even brain must be far more common. [...] Meanwhile, the death of a child from paralytic poliomyelitis had been described [...], in which a toxocaral larval granuloma was found in the brain, identified as due to T. canis. It was supposed that the worm larva might have carried a large dose of poliomyelitis virus from the gut to the brain. In consequence, the toxocara skin test was applied to a group of normal healthy persons, and to a group of persons who had suffered from paralytic poliomyelitis. The tests showed that toxocara infection had occurred seven times more frequently in those who had suffered from paralytic poliomyelitis than in those who had not. There is thus prima facie evidence that toxocara larvae may be an agent in the distribution of poliomyelitis virus through the body; they could be responsible for the spread of other infections also. The investigation was then extended to persons suffering from epilepsy. [...] [T]he skin test for toxocara was positive 3½ times more frequently in epileptics than in non-epileptics. It was concluded that some epileptic patients developed the condition as a result of toxocara larvae invading the brain and creating a focus of irritation there. Fiennes, R. N. T. W. Zoonoses and the origins and ecology of human disease. New York: Academic Press, 1978. |

|

Studies on the prevalence of T canis in dogs in the United States revealed that 20% to 21% of adult dogs and as many as 98% of puppies may be infected. [...] [A] combination of dogs allowed to defecate in areas of human habitation and a generally low level of personal hygiene make an ideal setting for transmission of Toxocara sp to humans.

Jones, W. E., Schantz, P. M., Foreman, K., et al. Human toxocariasis in a rural community. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 1980, 134, 967-969. |

|

The eggs [...] are sticky and readily adhere to the animal's coat, toys, carpets and other household articles. Eggs are able to survive a temperature of -25ºC and thus remain viable on the surface of the soil during the winter months even under snow.

Bisseru, B. Toxocara infections. In O. Graham-Jones (ed.). Some diseases of animals communicable to man in Britain. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1968. |

|

Ocular nematodiasis due to Toxocara canis occurred in a girl 6 years of age who had no history of contact with kittens or puppies, no history of an illness suggesting visceral larva migrans, and no eosinophilia. The left-eye inflammation was observed for over a year and changed very little. [...] The child must have ingested the ova in contaminated dirt, because no history of contact with puppies or kittens was obtained; in fact, the mother stated the patient had a dislike for these animals. [...] The infection must have existed for a considerable time prior to the discovery of the disease, for at the initial visit the process was quite advanced. In spite of this, the larva was in excellent health [...]. [...] The larva may appear quite healthy [...] for as long as seven years. Hogan, M. J., Kimura, S. J., & Spencer, W. H. Visceral larva migrans and peripheral retinitis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1965, 194, 1345-1347. |

|

Among patients with toxocariasis studied at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, London, it has been found that only about half have owned a dog or cat or had one in their home or had otherwise had close contact with one. This raised the question whether any significant amount of transmission was taking place from soil which had been contaminated by animal excreta [...]. The possibility of soil in parks and other public places being contaminated with the ova appeared worthy of investigation, and [...] it was found that among a total of 800 soil samples from such parks and public places 24.4 per cent contained ova of toxocara species.

Woodruff, A. W. Toxocara canis and other nematodes transmitted from dogs to man. British Veterinary Journal, 1975, 131, 627-632. |

|

Most studies in various parts of North America have demonstrated high rates of soil contamination in parks, playgrounds, and other public places [...]. [...] Dada and Lindquist [...] found contaminated soil in highway rest stops, parks and playgrounds. Children's sandboxes in university married student quarters frequently contained eggs of T. canis. Studies in Britain [...], Germany [...], and Czechoslovakia [...] showed similar rates of soil contamination in parks and playgrounds. [...] Helminth eggs are not destroyed by common forms of sewage treatment and are abundant in effluents and sludges. Viable eggs of Toxocara spp. were found in sewage sludge samples collected from 27 municipal sewage treatment plants in the southern United States [...]. When the larvae are larger in diameter than the blood vessel, their progress is impeded, and they actively bore through the vessel wall and migrate aimlessly in the surrounding tissue. Larvae wander extensively and have been found in the liver, lungs, heart, and brain [...]. The migrating larvae leave tracks of hemorrhage, necrosis, and inflammatory cells; most seem able to remain dormant for many years and then continue their migration. Eventually, some larvae are encapsulated and destroyed by a host response, while others are seemingly protected by being walled off [...]. Neurological manifestations including focal or generalized seizures and behavior disorders have been reported for up to 28 per cent of patients with VLM [...]. Since persons with OLM [Ocular Larva Migrans] are older and usually do not have a history of geophagia or exposure to puppies, it is reasonable to assume that their larval burdens are relatively small in contrast to the dirt-eating patient with VLM whose liver may harbor as many as 300 larvae per gram of tissue [...]. We hypothesize that at low doses of larvae the antigenic mass is insufficient to stimulate a marked rise in eosinophil and antibody levels. As a consequence, larvae migrate unimpeded through the liver and lung and incite minimal tissue response or clinical signs. These few larvae then enter the systemic circulation, from which they eventually penetrate capillaries and migrate randomly in host tissue. Most persons infected with small numbers of organisms will remain asymptomatic unless a larva penetrates through a retinal or choroidal vessel into the eye. Experimental evidence for non-human primates indicates that larvae can persist in tissues for at least 10 years [...] and can periodically resume migration; this pattern can mean a long incubation period for OLM. The incidence of human toxocariasis is unknown because toxocariasis is not a reportable disease in the United States, and the diagnosis is difficult to confirm in the laboratory. Neither worms nor eggs are passed in human feces and biopsy results are often uninformative despite widespread tissue invasion. Furthermore, the nonspecific nature of the clinical signs and symptoms probably results in substantial underdiagnosis. Despite problems in ascertainment, we know that toxocariasis occurs wherever humans live in close association with dogs. More than 1900 cases of this disease have been reported from 48 countries throughout the world and from every region of the United States. Ehrhard and Kernbaum [...] found that, of 780 well-documented cases of toxocariasis in the literature, 56 per cent of the patients were less than three years old and only 18 per cent were adults. Glickman, L. T. & Schantz, P. M. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of zoonotic toxocariasis. Epidemiological Reviews, 1981, 3, 230-250. |

|

About 50% of patients, many of them children, with the most serious forms of toxocariasis, including loss of sight in an eye, have never owned a dog or cat and have had only slight and transient contact with them. They probably acquired their infection from contact with contaminated soil in parks and public places. Chance infection of this kind by persons ignorant of the risks of contact with infective soil is responsible for much avoidable ill health.

Woodruff, A. W., de Savigny, D., & Jacobs, D. E. Study of toxocaral infection in dog breeders. British Medical Journal, 1978, 2, 1747-1748. |

|

No one knows the prevalence of visceral larva migrans. Several observations indicate that the chances of children coming in contact with fertilized eggs of T canis are extremely high. [...] These statistics, together with the knowledge that embryonated ova remain viable in 0.1N sulfuric acid for many months at icebox temperature, suggest that the risk for infection is quite high.

Zinkman, W. H. Visceral larva migrans. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 1978, 132, 627-633. |

|

Due to diagnostic difficulties, the frequency of larval infection caused by Toxocara in man is still unknown. Patients who suffer ocular invasion are those who most often seek medical assistance. It is possible, however, that for each ophthalmic case there may be several with larval infections in other organs, such as the heart, liver, lungs, and brain.

Acha, P. N. & Szyfres, B. Zoonoses and communicable diseases common to man and animals. Washington, D. C.: Pan American Health Organization, 1980. |

|

Demographic surveys indicate that between one third and one half of households in the United States have one or more dogs, most of which are infected with T. canis as puppies; therefore, opportunities for the infection � if not the disease � are very common. We do not yet know how frequently toxocara infections occur in human beings because the nonspecific nature of the clinical signs and symptoms leads to much underdiagnosis [...]. It may be that infection is much more frequent than is commonly recognized because investigation of other household members of patients frequently reveals many with eosinophilia and detectable toxocara antibody, indicating that considerable subclinical infection results from common environmental sources. [...] Unfortunately, the public-health hazard posed by toxocara infections in dogs and cats is rarely appreciated by pet owners, and thus they are often unwilling to take the measures necessary to minimize the risk of infection in family members. [...] One may be surprised at the frequency with which ova are found but if a little arithmetic is done the surprise vanishes. Twelve per cent of the dogs in Britain were found to be infected and there are at least seven million dogs in the country. That means that about 840,000 infective samples of faeces are deposited somewhere on British soil each day. That adds up to 276 million infective samples per year. It has been possible to keep such ova in the laboratory in the presence of formaldehyde for up to four years and to find that they remained viable throughout. If ova remain viable, even in formaldehyde, in the laboratory then the ova from 1500 million infective samples accumulate and are present in the soil of Britain at any one time. As many of these samples are deposited in public parks, it is not necessary to stretch the imagination to understand why so many samples were found infected. Measures for the control of transmission of toxocariasis First, licensing should be tightened up. Only about half the dogs in Britain at present are licensed. Second, a licence should be issued only if a certificate is given that the dog had been wormed properly by a veterinary surgeon or was known as a result of tests to be free from infection. Third, dogs ought to wear collars indicating that they had been licensed and as a corollary to this the police or other authorities should have power to impound those dogs not wearing collars indicating that they were licensed. Fourth, as there is no evident means of disinfecting contaminated soil, some degree of segregation of those areas where dogs and children exercise would be enforced and enforced with vigour. It is rare to find dogs prohibited from children's play areas in parks and public places. Even where there is prohibition it is often ignored. [...] Children should not play in places where dogs are continually contaminating the soil now that it is known that such contamination is dangerous. Fifth, much more vigorous segregation of dogs in public vehicles should be enforced, not just in trains, but in buses, and other public vehicles. [...] Sixth, there is also a good deal which could be done by simple public health education, by encouraging people to ensure that they wash their hands after they have played in public parks with balls and things that have come in contact with soil. Further they should ensure that, before washing their hands, they do not eat food or sweets, or these ova from the soil could be transmitted via their hands and fingers to their mouths. This is of particular importance when one remembers that children commonly eat sweets and play with balls in parks and, in handling sweets contaminate them and no doubt swallow numerous ova as a result. Woodruff, A. W. Toxocariasis as a public health problem. Environmental Health, 1976, 84, 29-31. |

|

Because it can safely be assumed that, as the possibility of contact with animal feces is reduced, so is the possibility of acquiring a parasitic infection, restrictions on where dogs can defecate are essential. The risk of parasitic disease can be reduced by enforcing more strictly the existing laws and bylaws concerning dogs, by expanding the bylaws to include areas not presently covered, and by informing the general public of their responsibilities both to their pets and to their fellow citizens. Present municipal bylaws [in Montreal] forbid that animals be allowed to enter markets or any other establishment where food is prepared, sold or served. These laws should be strictly adhered to and strongly enforced. Other bylaws state quite clearly that any dog, unlicensed or licensed, found off the property of the owner, except when held on a leash or under the control of a responsible person, may be seized by the police and taken to a public pound. Strict enforcement of this bylaw and more severe penalties to offenders would help to reduce the vast number of stray dogs and to control the licensed dogs. It is most important that dogs be discouraged from depositing their feces in areas where children come in contact with them � playgrounds and city parks in particular. Unfortunately, the law specifies only that dogs must be on a leash when entering a park. It would, perhaps, be more sensible to strictly prohibit dogs from all playgrounds and small city parks where children congregate. [...] Finally, the public should be made aware that a great deal of money and effort, both private and public, is needed to prevent "man's best friend" from spreading debilitating conditions ranging from diarrhea to blindness. Seah, S. K. K., Hucal, G., & Law, C. Dogs and intestinal parasites: A public health problem. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1975, 112, 1191-1194. |

|

Great care should be taken in handling or fondling puppies and bitches by both adults and children due to the stickiness of the Toxocara eggs which could be transferred to the hands and ingested. Children should be taught the habit of washing their hands after fondling dogs and other animals. They should not eat from the same utensils used by dogs and cats; moreover, people should not share their bed with canine and feline pets. Puppies and kittens should preferrably not be allowed into the house with children, as toddlers are in danger of ingestion of the animals' faeces, a gram of which may contain several hundred eggs. [...] Dogs and cats should not be allowed in food shops. Moreover, they should not be allowed to foul, with their faeces, playgrounds and parks which children have access to, streets and other public places. Bisseru, B. Toxocara infections. In O. Graham-Jones (ed.), Some diseases of animals communicable to man in Britain. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1968. |

|

Blindness caused by dog feces DARTMOUTH, N.S. (CP) � At least six Maritime children have been blinded in the past year by a parasite picked up from dog feces, a Halifax ophthalmologist said Thursday. Dr. Robert LaRoche, of the Izaak Walton Killam Hospital for Children, said two of the children have been successfully treated, but "the others have had tremendous visual loss beyond the point of legal blindness." In addition, LaRoche said the children's hospital is still treating six other cases which date back beyond this year. Authorities have long been aware dog feces often contain parasites that attack human tissue and causes infections, particularly in the eyes and lungs. The parasite, known as toxocara, is found in the intestines of animals. But when it infects humans, it can travel throughout the body. LaRoche said the parasite has to be ingested by mouth. This can happen when a child is licked by a dog that hasn't been dewormed or unknowingly picks up something on which a dog has excreted and later puts his fingers in his mouth. [...] WHEN THE PARASITES attack parts of the body other than the eye, the symptoms match those of other infections, making it difficult for officials to estimate the true number of cases. The parasite could result in a flu-like sickness with fever but it varies enormously from case to case, LaRoche said. "My suspicion is there's a lot more (cases) than we can see," said Dr. Scott Halpin, another pediatrician at the Killam hospital. A study by Dr. Juan Embic at the Killam showed 15 per cent of children are infected by the parasites, but most can fight it off. "Not everyone who comes in contact have blindness," said Embic. "But some of the kids who play in recreational areas are affected and (a few weeks) later produce this kind of disease." [...] The Saturday Windsor Star, 06-Dec-1986, p. C9. |

|

Press suppression of the health hazards of Spanish Banks dust clouds |

Mayor Philip Owen and Vancouver City Council Members [email protected] Dear Mr. Owen and members of Council: I bring to your attention the photographs below of Spanish Banks area beaches which show that back-lighting by a setting sun reveals clouds of particulate matter being thrown up by dry sand when it is disturbed:

The particulate matter is especially dense, and rises especially high into the air, in areas of high activity, as around beach volleyball courts:

Two questions arise in connection with the above dust clouds: (1) Of what are the clouds composed? Among the constituents may be pulverized organic matter, such as wood, seaweed, fish, insects, and fecal matter from birds and dogs. Also among the constituents may be mineral matter � essentially sand that has been ground down until its particles are small enough to become readily airborne. My first question for the Vancouver City Council: Has this Spanish Banks airborne sand dust been analyzed, and in what publications can any analyses be found? (2) How harmful are these dust clouds to human health? One imagines that if these same dust clouds filled factory air, health inspectors would close the factory down, or that if these same dust clouds filled City Hall, then City Hall would be evacuated. The case of sand dust perhaps deserves a lower level of tolerance than workplace dust in view of the large number of children who play on beaches, and in view of the large number of young people who spend hours in heavy physical exercise in the middle of the densest of the dust clouds. Among the viable hypotheses that spring to mind and that deserve evaluation are that throughout the summer, young lungs are being coated with particulate matter on Spanish Banks, and that this particulate matter leaves the lungs irritated if not damaged. My second question for the Vancouver City Council: Have the health effects of Spanish Banks airborne sand dust been discussed by medical experts, and in what publications can any discussions be found? As health considerations override most other considerations, it is conceivable that an exploration of the two above questions may eventuate in NO VOLLEYBALL signs � and perhaps other restrictions on activity � on sand that is particularly prone to throwing up dust. Certainly it might be discovered to be inadvisable to continue placing volleyball nets in locations where physical activity may be harmful to health. Yours truly, Lubomyr Prytulak, Ph.D. |

| What's it all about? |