|

|

Lubomyr Prytulak Ukrainian Archive, www.ukar.org [Address] 26 February 2003 |

| American Dollars | Canadian Dollars | |||

| Lawyer A | Lawyer B | Lawyer A | Lawyer B | |

| Retainer | 8,500 | 30,000 | 13,039 | 46,020 |

| Twice | 17,000 | 60,000 | 26,078 | 92,040 |

| Thrice | 25,500 | 90,000 | 39,117 | 138,060 |

| From this equation, can be inferred that |

this many binary questions |

are sufficient to identify this many species |

| 21 = 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 22 = 4 | 2 | 4 |

| 28 = 256 | 8 | 256 |

| 210 = 1,024 | 10 | 1,024 |

| 215 = 32,768 | 15 | 32,768 |

| 220 = 1,048,576 | 20 | 1,048,576 |

|

A judge shall be faithful to the law regardless of partisan interests, public clamor, or fear of criticism, and shall maintain professional competence in the law.

California Code of Judicial Ethics, Canon 3, Section B, Paragraph 2. |

|

This Canon does not preclude internal discussions among judges regarding the application of substantive or procedural provisions of law to any pending criminal or civil case.

Advisory Committee Commentary on Canon 2 of the California Code of Judicial Ethics. |

|

A judge may consult with court personnel whose function is to aid the judge in carrying out the judge's adjudicative responsibilities or with other judges.

California Code of Judicial Ethics, Canon 3, Section B, Paragraph 7b. |

|

A judge may obtain the advice of a disinterested expert on the law applicable to a proceeding before the judge if the judge gives notice to the parties of the person consulted and the substance of the advice, and affords the parties reasonable opportunity to respond.

California Code of Judicial Ethics, Canon 3, Section B, Paragraph 7a. |

|

An appropriate and often desirable procedure for a court to obtain the advice of a disinterested expert on legal issues is to invite the expert to file an amicus curiae brief. A judge must not independently investigate facts in a case and must consider only the evidence presented, unless otherwise authorized by law. For example, a judge is standardly authorized to investigate and consult witnesses informally in small claims cases. Advisory Committee Commentary on Canon 3, Section 7 of the California Code of Judicial Ethics. |

|

If a court at any time determines that there has been a change of law that warrants it to reconsider a prior order it entered, it may do so on its own motion and enter a different order.

California Code of Civil Procedure §1008(c). |

|

When a court upon motion of a party or its own motion finds that in the interest of substantial justice an action should be heard in a forum outside this state, the court shall stay or dismiss the action in whole or in part on any conditions that may be just.

California Code of Civil Procedure §410.30(a). |

|

A word about judges. The American people have an understandably negative view of politicians, public opinion polls show, and an equally negative view of lawyers. David Kennedy, professor of history at Stanford University, in writing about politicians, says: "With the possible exception of lawyers, we hold no other professionals in such contempt. Who among us can utter the word 'politician' without a sneer?" Conventional logic would seem to dictate, then, that since a judge is normally both a politician and a lawyer, people would have an opinion of them lower than a grasshopper's belly. But on the contrary, a $25 black cotton robe elevates the denigrated lawyer-politician to a position of considerable honor and respect in our society, as if the garment itself miraculously imbued the person with qualities not previously possessed. [...] Either the appointee has personally labored long and hard in the political vineyards, or he is a favored friend of one who has, often a generous financial supporter of the party in power. Roy Mersky, professor at the University of Texas Law School, says: "To be appointed a judge to a great extent is the result of one's political activity." Consequently, lawyers entering courtrooms are frequently confronted with the specter of a new judge they've never heard of and know absolutely nothing about. The judge may never have distinguished himself in the legal profession, but a cursory investigation almost invariably reveals a political connection. [...] Although there are many exceptions, by and large the bench boasts undistinguished lawyers whose principal qualification for the most important position in our legal system is the all-important political connection. Rarely, for instance, will a governor seek out a renowned but apolitical legal scholar and proffer a judgeship. It has been my experience and, I daresay, the experience of the most veteran trial lawyers that the typical judge has little or no trial experience as a lawyer, or is pompous and dictatorial on the bench, or worst of all, is clearly partial to one side or the other in the lawsuit. Sometimes the judge displays all three infirmities. Vincent Bugliosi, Outrage: The Five Reasons Why O.J. Simpson Got Away With Murder, Island Books, New York, 1996, pp. 105-106. |

Judge James R. Dunn dispenses justice to Defendant Lubomyr Prytulak | |

|

It is an emphatic postulate of both civil and penal law that ignorance of a law is no excuse for a violation thereof. Of course it is based on a fiction, because no man can know all the law, but is a maxim which the law itself does not permit any one to gainsay. ... The rule rests on public necessity; the welfare of society and the safety of the state depend upon its enforcement. If a person accused of a crime could shield himself behind the defense that he was ignorant of the law which he violated, immunity from punishment would in most cases result.

People v O'Brien (1892), 96 Cal 171, 176. www.geocities.com/tthor.geo/calgenlaw.html |

|

Federal rules reject the approach that pleading is a game of skill in which one misstep by counsel may be decisive to the outcome and accept the principle that the purpose of pleading is to facilitate a proper decision on the merits. [...] The ends of justice are not served when forfeiture of just claims because of technical rules is allowed. [...] "Thus, the Travelers Insurance Company 'hid in the bushes' so to speak and finally struck the plaintiff from ambush."

Judge Hickey of the United States Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit in Travellers Indemnity Co. v United States, 382 F2d 103 at 104, 106 (1967) |

Honorable Robert R. Jacobs II, Public Defender, Office of the Public Defender, 20th Judicial Circuit publicdefender.cjis20.org/miranda.htm |

|

Moreover, to perfect service pursuant to the long-arm statutes, the complaint must allege the jurisdictional requirements prescribed by the statutes. [...] Failure to adequately allege the basis for invoking long-arm jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant voids any service of process. • City Contract Bus Service, Inc. v Woody, 515 So2d 1354 at 1356 (Florida 1987) |

"Miranda-rights" equivalent, to be read at least to every non-resident civil defendant. |

|

|

| |

|

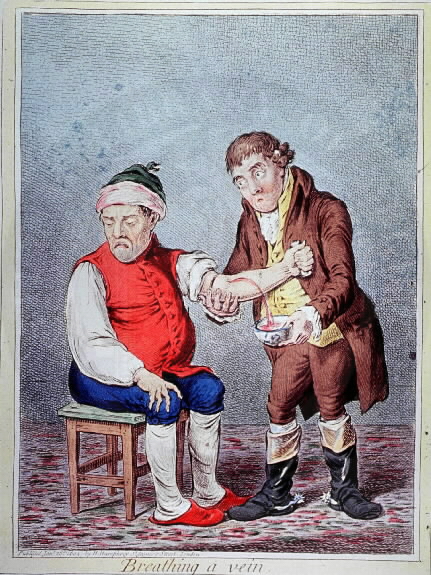

Mr. Samuel Breck, speaking of methods of punishment in his boyhood in Boston, in 1771, said: "A little further up State Street was to be seen the pillory with three or four fellows fastened by the head and hands, and standing for an hour in that helpless posture, exposed to gross and cruel jeers from the multitude, who pelted them constantly with rotten eggs and every repulsive kind of garbage that could be collected." Punishment Library, The Pillory www.rm-r.net/~getch/punishments/curious/chapter-4.html |

Rudolf Ackermann, Charing Cross Pillory, from William Pyne, Microcosm of London (1808), Spartacus Educational www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/LONcharing.htm |