|

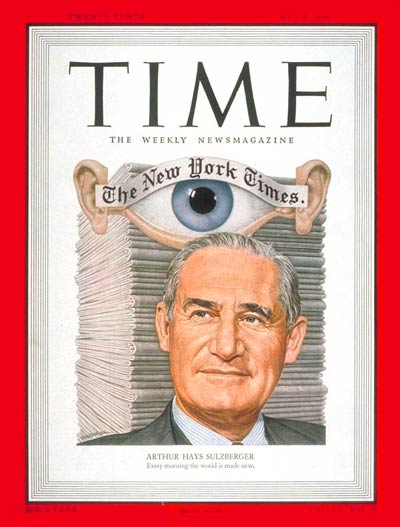

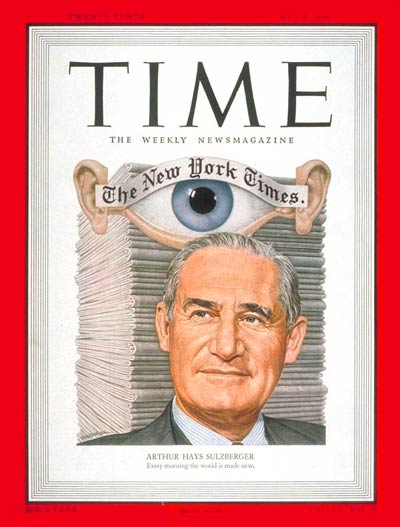

Arthur Hays Sulzberger President and Publisher SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 1947, P. 14 DICTATORS AND THE PRESS President Peron of Argentina has evidently been studying recent history. At least he knows, as a student of the period would learn, that control of the press has been essential to those who would rule with a heavy hand. This has been the case because it is only through a free press that the entire community can be made aware of the abuses imposed upon parts of it, and thus be afforded the opportunity to rally its collective strength in opposition to the minority that is seizing and misusing power. Soviet Russia furnishes the earliest lesson. Free press and free enterprise went out together. Neither disappeared immediately after the November revolution in 1917. At first the new regime did not eliminate the entire press but only a part of the bourgeois press, meantime making things as difficult as possible for the non-Bolshevik newspapers. But on June 28, 1919, the Soviet authorities decreed the nationalization of all large-scale industry, and in the events that swiftly followed freedom of expression and other civil liberties were extinguished. Italy came next. The suspension on Sept. 30, 1925, of Italy's second largest newspaper, the Turin Stampa, because of critical comment on the Italian maneuvers of that year, was not recognized by many Italians as the beginning of a process that would end with the extinction of all freedom. This should have made clear to them the meaning of the new Fascist press law, but it did not, since the Fascist violation of political rights seemed to a large part of the Italian people a small price to pay for "tranquility and security." They had no Benjamin Franklin to tell them that those who "give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety." They learned, to their sorrow, that liberty is indivisible. Germany was next in line. Prior to the imposition of press controls the circulation of daily and weekly newspapers in Germany supporting the Nazis amounted to less than 4 per cent of the total. The first press law, proclaimed Oct. 4, 1933, made all journalists semi-state officials independent of direction by their employers, and subject to registration and licensing by the state. The second series of decrees, in April, 1935, gave the party press of the National Socialists the right to suppress any competition and provided for the strict regulation of any "coordinated" newspapers still surviving. The last vestiges of press and other freedoms were swiftly extinguished. Franco Spain gave another demonstration of the inseparability of all private rights and freedoms. When Franco achieved power, Falange dictators were installed in all party newspapers; plants of opposing newspapers were confiscated; newsprint was rationed by a Falange syndicate; all newspaper men were licensed and unable to engage in their profession without a permit. Press freedom, there as elsewhere, ended with other civil liberties. President Peron's latest move against the Argentine newspapers is a decree providing for government "acquisition and expropriation" of newsprint, in which opposition papers, facing a newsprint crisis early in 1948, see increased evidence that the Government seeks to establish a monopoly in newsprint for the purpose of squeezing out critics. This is the classic first step by which dictatorship is imposed upon a people. By its very nature, dictatorship moves inexorably to stifle the voice of a free press and to destroy the sources of trustworthy information which are essential to an intelligent and effective public opinion. In following in this respect the pattern endorsed by Stalin and Hitler, Mussolini and Franco, Senor Peron has embarked on a course of infinite danger to his country. We honor the great newspapers of Buenos Aires, La Prensa and La Nacion, which still carry on the critical and decisive battle for a free press in Argentina. |