Published February 21, 2001

Israel's Favored Ammo is Crippling a Generation of Young Palestinians

Shoot to Maim

by Lamis Andoni & Sandy Tolan

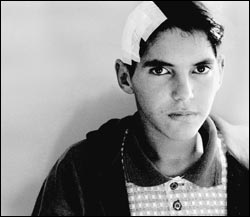

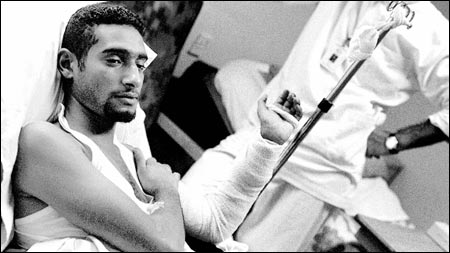

Ahmed Zakhi, 15, spent

20 days in a coma.

photo: Heidi Zeiger

|

|

Held up to the light, the X ray of Fouad Mahed's right femur resembles a piece of the sky on a clear desert night: countless specks of white scattered against an ink-black backdrop.

But this milky way is actually hundreds of fragments of lead and bone, the result of a bullet from an Israeli rifle that shattered Mahed's leg. The image itself is of something that no longer exists. After massive blood loss, doctors were forced to amputate the limb two weeks after the shooting.

"Surgery is easy when you know the anatomy," says Dr. Nasri Khoury, tracing the outline of Mahed's femur with a pen. "But when the anatomy is destroyed, the surgeon is at a loss."

Thousands of Palestinian young men and boys may become permanently crippled from bullet wounds suffered during the last five months of stone-throwing protests against Israeli rule. As with Fouad Mahed, a carpenter from Gaza, many of the 11,000 injuries came when unarmed people were shot.

|

This investigation was conducted under the auspices of the University of California at Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, with reporting by Sara Dunn, Chris Smith, and Gavin Tachibana in Amman; and Aryn Baker, Jessie Deeter, and Robin Shulman in Jerusalem and the West Bank. |

The high rates of crippling injuries are in large part due to the fragmenting bullets fired by M16s. The American-made Colt weapons, introduced during the Vietnam War as lightweight field rifles capable of inflicting maximum damage on the enemy, are being used increasingly by the Israel Defense Forces against civilian demonstrators. The M16 ammunition often breaks into tiny pieces after penetration, ripping up muscle and nerve and causing multiple internal injuries, much like those of the internationally banned dumdum bullets.

Forensics experts in the United States and Europe, who agreed for this article to examine the X rays of Fouad Mahed and other wounded Palestinians, confirm repeated casualties from M16s, shotguns, and other live ammunition. These images, together with other X rays seen in West Bank and Jordanian hospitals, show a pattern some forensics specialists call a "lead snowstorm," the fragmentation of high-velocity military ammunition, fired at civilians. Many of the wounded were hit at short range—less than 100 meters—compounding internal damage.

The reliance on these rounds is part of what human rights groups have denounced as excessive use of Israeli force against mostly unarmed Palestinians. "Shooting people with high-velocity bullets to wound them is a form of summary punishment being inflicted in the field," says Dr. Robert Kirschner of the Nobel Prize-winning Physicians for Human Rights.

It's not yet clear how newly elected prime minister Ariel Sharon, a lifelong hard-liner, will handle the spiraling conflict. Last week the IDF sent helicopter gunships to assassinate a senior Palestinian security officer. The next day, a Palestinian bus driver plowed into a bus stop, killing seven Israeli soldiers and one civilian. Charges continued that Israeli troops were firing live ammunition into unarmed crowds before trying to scatter them with tear gas or water cannons, as the military code requires—the same charges the IDF denied under Sharon's predecessor, Ehud Barak.

"Every new victim wounded or killed is not a goal for us," says Major Olivier Rafowicz, a spokesperson. "The violence is initiated by the other side. If they can show victims, wounded, blood, children—it is only serving the Palestinian interest: 'See, we are only doing popular activities, and the bad Israeli guy is killing us for nothing.' We are not interested in that on the Israeli side."

Major Rafowicz argues that Israel has exercised considerable restraint in the face of life-threatening demonstrations, with gunfire from Palestinians. In addition, he says, Israel has tried unsuccessfully to acquire nonlethal riot control from several European countries. Nevertheless, Rafowicz insists, IDF soldiers operate under strict rules of engagement. "We open fire only on people who are endangering our lives," he says. "You can kill someone with a rock. A stone is a weapon."

Adds another IDF spokesperson: "We don't shoot live bullets when nobody's shooting at us."

Yet in more than 100 interviews for this article, patients, doctors, and medical personnel in 14 hospitals and clinics in Jordan and the West Bank paint a far different picture. With no shooting from the Palestinian side, and often little or no use of tear gas to disperse the protests, Israeli soldiers have repeatedly fired live ammunition into unarmed crowds.

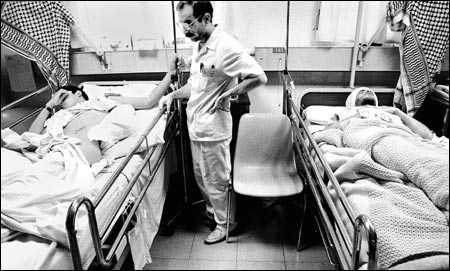

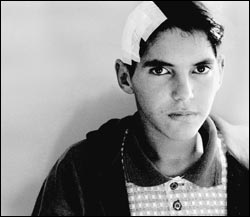

Fadi Mohammed, 18, (left) is paralyzed in both legs.

photo: Heidi Zeiger

Ibrahim Mustafa Darwish, 17, was shot in the abdomen on November 15, during protests at the Erez checkpoint that divides Gaza from Israel. Six weeks later, he lies in bed at Jordan Hospital in Amman. The bandages on his abdomen are bloody and sticky, signs of multiple surgeries to remove a meter of intestines. Israeli soldiers fired at the 18 stone-throwers from a distance of 15 meters.

Fadi Mohammed, 18, was also shot in the abdomen in late November while throwing rocks at a protest. The single bullet exploded two vertebrae, injuring his kidney and paralyzing both legs. He arrived November 30 at Palestine Hospital in Amman, where surgeons removed his spleen and parts of his vertebrae.

Mahmoud Al Medhoun, 15, was hit three times—in the leg, back, and abdomen—by soldiers firing from the hatch of a tank. One bullet lodged in his spine, smashing three vertebrae and pinching a nerve. His right leg is paralyzed. Doctors have removed part of his colon and repaired his liver; he is unable to eat. "God willing, I will walk again," declares Mahmoud. But when his father cites the doctors' opinion that the paralysis is probably permanent, the boy rolls himself into a ball, burying his face in the crook of his arm and crying.

Crippling injuries among Palestinians are estimated at 1500—a figure likely to rise as more of the wounded seek rehabilitation. Palestinian officials say the rate of disabling injuries during this Al Aqsa Intifada, which began in the shadow of East Jerusalem's Al Aqsa Mosque on September 29, is higher than during the first intifada, which lasted from 1987 to 1993. "The Israeli response to this intifada has been more ferocious, swifter, and more intensive," says Dr. Mustafa Barghouti, head of the Union of Palestinian Medical Relief Committees.

Lethal fire has come from M16, M3, and M24 snipers' rifles, and from higher-caliber munitions, including concrete-busting machine-gun bullets, grenade launchers, 120-millimeter tank shells, and Hellfire rockets fired from American-made Apache attack helicopters. The heavier fire, say Israeli analysts, has come in response to Palestinian sniping. But even the more benign ammunition designed for riot control, like so-called rubber bullets—steel balls coated with a thin layer of rubber—can be fatal if fired at short range. "They are the nightmare of the neurosurgeon," says Dr. Jihad Mashal. "Every time the patient moves his head, it's like a marble moving in jelly. There's nothing you can do about it."

In the first weeks of the Intifada, head and upper-body injuries accounted for a great portion of Palestinian casualties. "A large part of those wounded by live bullets are those we indeed wanted to not only injure but kill," wrote General Giora Eiland in a letter to Israeli human rights lawyer Neta Amar. "These are the same people that shoot at us with live ammunition. The fact that most of them are wounded in the upper body or head is a positive thing."

After a flurry of international condemnation, the rate of head and chest injuries dropped, replaced by devastating leg and abdomen wounds. "I consider it a form of torture," says Kirschner of Physicians for Human Rights. "There's no question in my mind that this was a very conscious military decision to use this weapon to wound people as a form of intimidation of the population. And as a result, probably several thousand young Palestinian men will end up with permanent disabilities."

The M16 ammunition was at first mistaken by Palestinian doctors for the dumdum bullet, banned by the Hague Convention in 1899. "Many people think that it's a dumdum bullet, because if it does penetrate deep enough, it will break," says Martin Fackler, a former army surgeon who now runs ballistics tests for the U.S. Department of Defense. "Fragmentation does cause more wounds."

The weapon was introduced in 1963, as an experiment with the South Vietnamese army during the Kennedy administration. Soon reports came back from the field, recounted in a 1995 article in the International Review of the Red Cross, of a bullet that "does cartwheels as it penetrates living flesh, causing a highly lethal wound that looks like anything but a caliber .22 hole." By 1966, army doctors reported "gaping, devastated area[s] of soft tissue and even bone, often with loss of large amounts of tissue" and a disintegrating bullet. Seven years later, reports were circulating about wounds that looked like those caused by the expanding dumdum bullets, banned for causing "superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering."

Years of experiments revealed that the lightweight M16 bullet was prone to "yaw" and "tumble" more quickly after penetration—giving it greater potential to rip apart tissue by flying through the body sideways. The higher velocity—a trait now shared with other military rifles—also meant the bullet created a larger "temporary cavity," destroying solid, less flexible tissues like the spleen and liver—a pattern of injury borne out in Palestinian medical records. And the bullet fragmented more, causing multiple injuries from tiny pieces of lead, each on its own haywire path.

The old dumdum had been banned from the battlefield, but now some worried that a new bullet, with similar consequences, was taking its place. For years, disputes over what actually caused the wounds—the bullet's velocity, its tumbling, its fragmentation—slowed efforts to ban the ammunition. In 1995, the Swiss introduced an initiative to bring the M16 ammunition, along with others, under the umbrella of the Hague Convention. In his analysis of the Swiss effort in the International Review of the Red Cross, the humanitarian scholar Eric Prokosch urged states to "seize the opportunity" for the "adoption of the strongest possible ban on the modern dumdum bullets."

Some ballistics experts in Europe agree. Dr. Peter J.T. Knudsen, a Danish forensic pathologist who has written extensively on bullets and humanitarian law, argues that all M16 ammunition currently used by military forces should be banned, because they all tend to shatter. "Fragmentation adds unnecessary suffering and superfluous injury," he says.

Others caution that the M16 should not be singled out in what amounts to a political struggle rooted in the Cold War.

"The concept of 'inhumane' rifle bullets is a product of minds who know nothing of real war, and usually have ulterior—usually political—motives," says Fackler, who points out that heavier military bullets, with greater mass, also produce large wounds. "I have seen many soldiers who have had both legs and an arm blown off by explosive devices: land mines, artillery, etc. That is inhumane. There are no rifles on the battlefield that can disrupt anywhere near that much tissue. So does it make good sense to declare a rifle bullet inhumane and ignore the weapons that cause far more tissue disruption?"

Defenders of the M16 say attempts to ban the rifle's 5.56mm ammunition were started by the Soviet Union, envious of the U.S. and NATO's lightweight, efficient military rifle. That claim is disputed, but the issue remains politically charged. After years of testing and repeated international meetings, some humanitarian and ballistics experts would like to raise the issue of high-velocity, fragmenting bullets at an international conference in Europe later this year. They say it's time that weapons causing the same degree of unnecessary harm as the old dumdum bullets be placed under the same kind of ban.

Chances for that appear slim. After floating a proposal that might have put restrictions on the M16 ammunition, potentially forcing NATO countries to develop entirely new, nonfragmenting ammunition, the Swiss government now appears ready to offer a more modest plan.

"Can you imagine if there were an attempt to ban 5.56[mm] bullets?" asks Denmark's Dr. Knudsen. "Think about all the countries that would have to discard all their M16 ammunition." Even if they replaced it with the nonfragmenting bullets being tested, there's still a stark political reality: None of the "safer" bullets are manufactured in America. "Imagine if you told the U.S. Army they would have to buy all their bullets from a foreign country," Knudsen says. "Or how about the senator in whose state the bullets are made? There's too much money involved."

As humanitarians debate whether to consider a ban on ammunition they believe excessively harmful to soldiers, the IDF continues to use the weapons on unarmed Palestinian civilians. Live ammunition has been used "routinely in an illegal and indiscriminate manner," a Human Rights Watch report said of the IDF, "resulting in deaths and injuries to civilians."

|

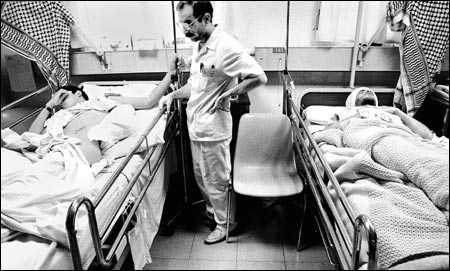

Mohammad Nada, 17, will need a nerve graft to regain full mobility in his left leg.

photo: Heidi Zeiger |

Nasri Showkat lies in his bed in Jordan Hospital, waiting for doctors to extract the last bullet fragments, lodged near his left eye socket. The graying edges of his short black hair and his thin silver-frame glasses give a learned look to Showkat, a history major who was due to graduate this year. On October 25, he joined hundreds of demonstrators in Ramallah. They marched to the Israeli-guarded checkpoint and threw their stones. When Showkat saw his friend shot in the head, he rushed out and was himself shot, he says, by a sniper. The bullet hit Showkat in the upper lip, exploding into seven fragments inside his head. He lost the teeth on one side of his mouth, which he covers with one hand when he tries to speak.

Amjad, 22, was hit in the head in the West Bank town of Jenin. X rays show a bullet lodged in the back of his skull. His arms are listless and floppy like a rag doll's, and the room smells like excrement.

Mohammad Nada, 17 years old, was shot twice by an Israeli sniper on December 1 while clearing debris in front of his sister's house, close to the site of daily clashes in Ramallah. The second shot went into his left buttock and hit his sciatic nerve, which controls the up-and-down movement of the foot. X rays show evidence of a high-velocity bullet, which fragmented into hundreds of pieces. Doctors say he needs a graft to repair the nerve.

Isa Abu Abdullah, 19, was confronted by Israeli tanks in Gaza on the third morning of Ramadan, November 29. He threw stones, then was hit by a bullet in the left calf. While down, he was hit by six more bullets: three in his left thigh, two in his right thigh, and one in his right arm. Doctors at the Shifa Hospital in Gaza moved part of an artery from his right leg to his left, then sent him to Amman for further surgery.

Mahmoud Odeili, 23, lives in Gaza, near the Israeli settlement of Gush Katif, a constant flashpoint. Now he fills a bed in Amman's Shmesani Hospital. The unemployed father of two barely opens his mouth when he speaks, because of the high-velocity bullet that smashed his jaw before exiting through the back of his neck. He says he and his friends ran out to throw stones at an Israeli demolition crew sent to destroy their houses. He was shot by a soldier in a tank 100 meters away. "They shot us and kept going," he says.

"How many patients do you want to see?" asks Dr. Ghazi Hanania of the Abu Raya Rehabilitation Centre in Ramallah. The doctor, in a gray charcoal suit with a red scarf, looks across his desk with deeply tired eyes. "You can talk to 2000 patients if you want to."

Outside the center, four young men in wheelchairs gather at the curb, soaking up the December sun. Nasser Bilali, his leg in a heavy cast, says he was just walking home when clashes broke out. In the confusion he was hit by a high-velocity bullet that shredded several bones in his left foot. He's not sure if he'll walk again without crutches; it will be months before he can even think about going back to work. "I can't consider myself a hero," says Bilali. "Because I didn't even throw stones. I was just walking and I got shot."

An old woman in a white headscarf and a black Palestinian dress has been listening to Bilali's story. She begins to yell and wave her arms. "Look at him! He's young, and he's already in a wheelchair. Haram! Haram! This is a crime! This is a crime! We're using stones. They're using bombs and rockets and tanks!" She points to the rehab center's second floor. "My son is upstairs. A woman pours out the blood of her heart to raise a son through poverty and hardship, and now he gets shot."

Dr. Hanania says he is not so worried about the hundreds of patients his staff is contending with now. "The problem is what will be coming to the center in the coming days," he says. Because the Israelis are limiting freedom of movement between West Bank towns and villages, the doctor says, it's impossible to estimate how many young men will need rehabilitative care. But when the roads open, Dr. Hanania expects a flood. "There are reports that there are 25 to 30 percent of the injured in need of rehabilitative care"—several thousand people, given the current casualty figures. "If that's true, it's a national disaster."

Across the Jordan River in Amman, Dr. Khoury pulls back Fouad Mahed's bedcovers to reveal a bandaged stump—the remnants of his right leg. After he was hit, doctors in Gaza pumped 17 pints of blood into Mahed, to replace that which was pouring from the wound. Complications from a skin graft forced doctors to send him to Amman, where he could get treatment unavailable in the Gaza hospitals.

Khoury has operated on hundreds of injured Palestinians dating back to the first intifada. But never has he seen so many severely wounded. He puts his hand on Mahed's shoulder. "This guy is amazing," says Dr. Khoury. "After all he's been through"—the shooting, the amputation, the formation of ulcers that almost killed him—"the smile never leaves his face."

Mahed was shot in Gaza just after returning home from an afternoon of prayer. Israeli shells began to fall in his Khan Yunis neighborhood, 100 meters from an Israeli military installation. When parts of his ceiling caved in, Mahed, who says he has never taken part in the protests, decided to bring his wife and daughter to his brother's house. Just outside his door, he was hit.

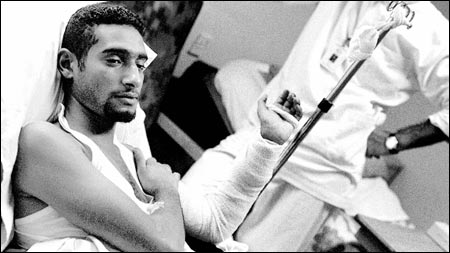

Mohammed Mahmoud Abu Fodeh, 22, was shot in the arm, chest, and lung.

photo: Heidi Zeiger

The question of whether lethal force is justified rests in determining whether police or security forces are acting to defend themselves or others against the threat of imminent death or serious injury. Israeli officials say they are shooting in response to shooting. "The Palestinians are not only throwing stones like 10 years ago," says Major Rafowicz of the IDF, "but also using rifles, Kalashnikovs, within the demonstration."

Even in such cases, Israeli forces, supported by tanks and high-caliber fire from helicopter gunships, have often overwhelmed the Palestinian side. "Usually the Palestinian fire is pathetic," an anonymous IDF sniper told the Israeli newspaper Ha'aretz. "The shooting is totally pathetic. . . . You know that most of it will be into the air."

Despite headlines describing a conflict between two armies—and despite repeated calls from Israeli and U.S. officials that it is the Palestinians who must stop the violence—approximately 90 percent of the dead and wounded have been Palestinians or Israeli Arabs. The IDF's own figures indicate that in three-quarters of the clashes, there was no Palestinian gunfire. "Israel's policy is directed in large part against the Palestinian civilian population, which is not firing at Israeli civilians or IDF soldiers and is the primary victim of Israel's human rights violations," says a recent report by B'tselem, the respected Israeli human rights group.

Of the dozens of patients interviewed in the 14 hospitals, all but four said they were throwing stones, coming to the aid of another wounded person, or simply walking past a flashpoint when they were shot. One patient admitted to firing a gun when hit; three others said they were throwing Molotov cocktails.

"Molotov cocktails can kill," says Major Rafowicz.

According to human rights groups, even the gasoline bombs pose little threat to soldiers equipped for riot control. "The Israeli security services were almost invariably well-defended, located at a distance from demonstrators in good cover, in blockhouses, behind wire or well-protected by riot shields," Amnesty International concluded in its October report. "Certainly, stones—or even petrol bombs—cannot be said to have endangered the lives of Israeli security services in any of the instances examined by Amnesty International."

The Palestinians, by comparison, have been easy targets.

Shadi Masri, 24, was shot three times in the abdomen on November 16, after throwing Molotov cocktails at a tank. Beside his bed at Amman Surgical Hospital stands a Palestinian flag. On the wall hangs a poster of Yasir Arafat, superimposed over a crowd of protesters. Masri doesn't know how long it took him to get to Jordan, but says he does remember Israeli soldiers taking his picture and punching him in the ambulance. It was the third time he was injured during this intifada.

Mohammed Bassam, 15, was shot while protesting on November 26 in Birzeit, near Ramallah. A high-velocity bullet went through his shin, crushing the bone. Surgeons inserted steel rods through his leg and an "external fixator" resembling perforated file-cabinet rods. He uses a walker to get around his hospital room.

Adil, 31, was shot during what he says was a peaceful protest following a funeral of a man killed in the clashes. A bullet splintered a bone in his left leg. Adil says he saw fragments of the limb in the street before he passed out.

Morad, 15, breathes slowly, with the aid of a respirator. The machine clicks, his chest fills with air, it clicks again, his chest falls. His eyelids are purple and swollen, his head wrapped in a bandage. A heart monitor is connected to his chest. A bullet is lodged in his brain.

Sharif Darwish, 34, sits sideways on his bed at Hussein Hospital in Beit Jala, near Bethlehem. A heavy cast holds in place the shattered bones of his foot. "The guy who carried me to the ambulance was killed," he says. Darwish stares ahead at nothing. A few weeks before, a rocket hit his Beit Jala house, landing next to his bedroom. "I had just woken up to get some breakfast," he says.

Palestinians, almost without exception, trace the beginnings of the Al Aqsa Intifada to the September 28 arrival of Ariel Sharon at Haram al-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary, or Temple Mount to the Israelis), backed by a thousand Israeli troops and riot police. The high casualties, they say, began as part of a brute-force strategy by then prime minister Ehud Barak to try to achieve a swift end to the conflict.

"These are good tactics if one wants to wipe out an enemy," said Dr. Stephen Males, a former senior police officer in the U.K. who accompanied an Amnesty International fact-finding team to the region. "They are not policing."

Israelis say Sharon's visit was merely an excuse to adopt a carefully orchestrated intifada planned and backed by the Palestinian Authority. "We are talking about a very organized and very planned violent strategy chosen by the P.A. to try to achieve political goals from the very beginning," says Major Rafowicz. "To try more quickly to achieve political objectives, mainly, we believe, to improve the Palestinian position abroad by reinforcing the image of the underdog of the big, bad Israeli.

"We have been dragged into this situation not by our own policy. We look very bad on TV because we are a regular army facing a so-called popular demonstration. But on the other side it is a strategy."

Publicly, IDF officials keep to their explanations of restraint in the face of violence. General Eiland, in his letter to the Israeli human rights lawyer, wrote: "[W]ithin a rioting crowd of unarmed residents, there are also those . . . who are armed. You cannot demand of a soldier to shoot only when he is convinced there is no danger for whoever stands next to a Palestinian opening fire at him."

Privately, some IDF soldiers and generals have been telling Israeli journalists something else. "I don't know if the IDF takes revenge," an IDF sniper told the newspaper Ha'aretz. "But every time, after there's a serious incident, it's political, you can feel it. You as a soldier know that if in the papers today they have written about a lot of things that happened to the IDF, then they will allow you to shoot more."

The sniper told Ha'aretz that soldiers are allowed to shoot at Palestinians who pose a potential threat, as long as they appear to be over the age of 12. "Twelve and up is allowed," said the sniper. A senior IDF officer told another Ha'aretz reporter: "Nobody can convince me we didn't needlessly kill dozens of children."

The high casualties sustained by Palestinians during the first two months of clashes, and the international condemnation of Israel that followed, have prompted a shift in tactics on both sides. Casualties began to decline in December, says Ghassan Khatib, director of the Jerusalem Media and Communications Center. He calls that decrease "a sign of fewer massive demonstrations at Israeli army checkpoints."

This is not an indication of renewed faith in the prospects for peace. Palestinians, says Khatib, have lost faith in an Oslo process that they no longer believe can deliver on basic issues of sovereignty, Jerusalem, and the right of Palestinians to return to their homeland. Increasingly, says Khatib, Palestinians are equating discussions of peace and security with the continuation of the Israeli occupation. A recent poll by the Jerusalem Media and Communications Center shows two-thirds of Palestinians support the most extreme measures, including suicide bombings, "under the current political conditions." The poll also indicates 70 percent of Palestinians support continuing the Al Aqsa Intifada.

In the hospital interviews in Jordan and the West Bank, young men appeared eager to again pick up the stone.

Mohammed Mahmoud Abu Fodeh, at 22, is already a veteran of the Palestinian struggle. Now, he lies in a bed in Amman's Specialty Physiotherapy Hospital, after being shot twice while protesting at the checkpoint between Jericho and the Allenby Bridge into Jordan. One high-velocity bullet lodged in his left shoulder. Another pierced a lung. His friends thought he was dead, until they saw him crawling toward the ambulance. The bullet from his chest rests in a jar beside his bed, "for memory and for evidence," he says.

"We're not afraid of their bullets, but they fear our stones," he says. "God gave us the stone—it has God's will in it. It's all we have.

"The stone has awakened the Arab world, from the leaders to the laymen," he says. "This is only the beginning."