Tuesday June 6, 2000 p. A12

Deprived Ukraine City

Finds U.S. Help No Help

Reward for Shunning Iran Project Falters

By PATRICK E. TYLER

|

Kharkiv, the industrial hub of Ukraine, was not on the itinerary. |

But because people here are so unhappy with the initiative's results, his visit was limited to Kiev.

The initiative is a program to show off this city of heavy industries, power blackouts and high unemployment to American investors. This is being done as compensation for Ukraine's decision to give up multimillion-dollar contracts to help Russia build a nuclear power plant in Iran, which is proceeding anyway on Persian Gulf coast of Iran at Bushehr without Ukraine's participation.

Two years ago [1998], the Clinton administration persuaded the Ukrainian government to order Turboatom, a producer of giant steam turbines and one of this city's largest enterprises, to back out of the Iranian project. The move was regarded as a great success of American policy, and it was expected that it would seriously disrupt Russia's ability to complete the Iranian power station.

Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright traveled to Kiev in March 1998 and praised President Leonid Kuchma for "great statesmanship" in joining the struggle to "halt the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction."

But today, construction at the Bushehr power plant is well under way, and Russia's deputy minister for atomic energy, Bulat I. Nigmatulin, says it will be completed in 2002. Russia is expected to earn about $1 billion from the project.

Part of that will go to its largest turbine manufacturer, a St. Petersburg company, which has taken over Ukraine's contract to produce the turbine that will be delivered to Iran in September 2001, said Viktor S. Shevchenko, the factory's executive director.

In the end, the only party that was hurt by American intervention was Ukraine, which the United States has been trying to help become an economically independent nation.

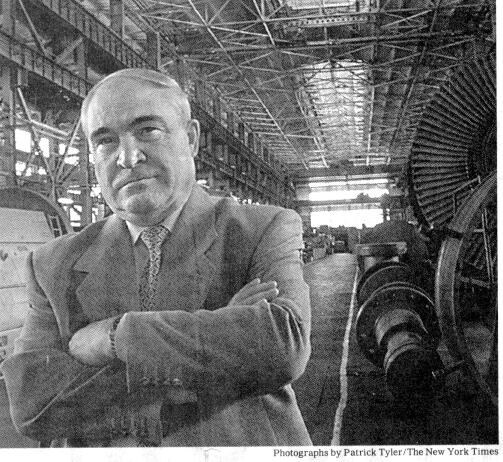

"This was one of our biggest contracts, and losing it has been a very serious blow to the economy of our region," said Anatoly A. Bugaets, Turboatom's general director. "But of course we are law-abiding people, and when a decision is made at the highest level, we have to obey."

Here in Kharkiv, in retrospect, it is difficult to find anyone who thinks that it was a good thing for Turboatom to walk away from tens of millions of dollars in contracts with its industrial partners in Russia for the sake of a weapons-nonproliferation objective that — here at least — seems somewhat fuzzy.

The United States and Ukraine may have stood together, however unsuccessfully, to oppose the sale of civilian nuclear technology to Iran, but no one in Ukraine, and especially in this city, is taking a victory lap around the idle factories of Kharkiv

|

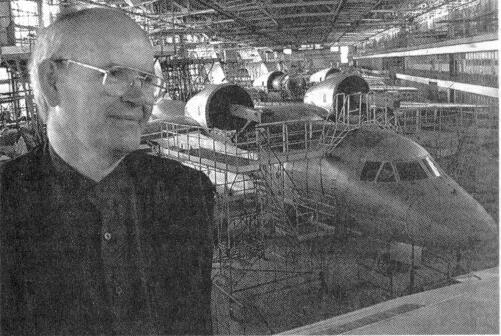

Anatoly A. Bugaets, [above], the director general of Turboatom, says the loss of a contract to build a nuclear plant in Iran was a major setback for his company. Anatoly Myalitsa, [below], general director of Kharkiv Aircraft, hopes to sell the company's transport jets in North America. A promise of help from the United States has born little fruit in Kharkiv. |

|

Nearly a decade after independence, Ukraine's broken deal with Russia over the Iranian plant is emblematic of a lament often expressed here and in the capital, Kiev. It is that Ukraine's agenda for economic development in the post-Soviet era never seems to be as important as the strategic objectives of the United States and its Western allies.

Ukrainian officials point to a series of actions sought by the United States: closing Chernobyl, the site of the world's worst nuclear accident; destroying old missile silos, and putting up high-tech security barriers to keep nuclear physicists who are begging for work from sharing information with the wrong countries. The Ukrainian officials point out that the United States has achieved nearly all of its strategic objectives in this former Soviet republic — eliminating nuclear weapons, making Ukraine an unofficial partner of NATO and, in the case of Turboatom, using Ukraine in an attempt to destabilize Russia's dealings with Iran.

Ukraine has been one of the leading recipients of American foreign aid in recent years, with about $200 million a year, much of which has gone to nuclear safety needs. But the nation remains mired in a kind of post-Soviet purgatory of economic and social lassitude as well as endemic corruption.

"A nation at risk" is how the Central Intelligence Agency described Ukraine in a mid-1990's report, warning that a seriously depressed economy, corruption and fiscal and monetary chaos were threatening its long-term survival.

Though there are signs that the Ukrainian economy is beginning a recovery after a decade of unceasing contraction, the Kharkiv Initiative, the payback for what Ukraine has sacrificed at Washington's insistence, has failed to generate a single contract for any industry in this city. Indeed, it has taken two years for the State Department to open an office here, which is now staffed by a single contract employee.

"Of course, we are disappointed," said the Kharkiv regional governor, Oleg Dyomin, who will travel as a guest of the State Department to New York, Cleveland and Chicago this summer in his continuing search for American corporations willing to invest in a country with serious corruption problems and an unstable electrical supply. Mr. Dyomin will bring color brochures of the Antonov jet transport produced here, of the Kharkiv tractor plant lineup, of the high-energy physics laboratories and of Turboatom, with its cavernous and nearly empty production lines.

"We haven't had any help yet," said Anatoly Myalitsa, general director of Kharkiv's aircraft plant. "We are not competitors. We only want a tiny piece of your market in the far north, where our aircraft is very capable of making short takeoffs in the snow. Why would America, a big country, not want to help small Ukraine?"

In an interview last month [May] in Kiev, President Kuchma put on a pained expression when the subject of the Kharkiv Initiative came up. "I don't want to offer any comment on this," he said. "It hurts too much, and in fact, it is a strong point of criticism that I get from my opponents."

One Western businessman, who has observed Ukraine's painfully slow emergence as a state, tried to capture the mood here by saying, "Disillusionment is too strong a word, but disappointment may not be strong enough."

Any notion that Mr. Clinton might visit Kharkiv was overruled, Western diplomats say, by concerns that he might be jeered by unemployed workers from Turboatom, where the Iran contract was expected to provide 25 to 30 percent of the factory's total output over five years.

Ever since Russia signed a contract with Iran in 1995 to complete the Bushehr power station, abandoned by German constructors in 1979 with the onset of the Iranian revolution, the Clinton administration has opposed it and Congress has threatened sanctions against Russia. And for the last two years, Congress has reduced by half foreign aid payments to Russia's central government, specifically because of the refusal to abandon Bushehr.

United States intelligence agencies have long believed that Iran has a secret program to develop nuclear weapons, dating back even to the rule of Shah Mohammed Riza Pahlevi, which ended with the 1979 revolution. Just the idea that Iran wanted to generate electricity with nuclear power instead of using its abundant oil and gas resources was suspicious, and still is for many experts.

American officials do not regard the Bushehr project as a source of nuclear material that could be diverted to an illicit bomb-making program. But the administration has taken the view that the Bushehr project will train an entire generation of Iranian physicists and engineers in nuclear technologies, and thus enhance Iran's scientific base, including any program to develop nuclear weapons. Israel, whose leaders also see their security threatened by Iran's nuclear program, joined in the diplomatic offensive to kill the project, but to no avail.

Russian and Iranian officials point out that Iran has placed the Bushehr plant under the rigid safeguards and inspection regime of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

In the last five years, when Boris N. Yeltsin was president of Russia, Dr. Albright and Vice President Al Gore undertook a number of missions to try to persuade him to cancel the Bushehr contract. But Mr. Yeltsin would not relent, promising instead not to expand Russia's nuclear cooperation with Iran beyond Bushehr, where as many as four reactor and turbine units are planned.

The project has suffered some setbacks. The original contract envisioned a four-and-a-half-year construction schedule. But Iranian construction companies were not able to repair the German foundation work — bombed during the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88 — in accordance with Russian specifications. Under a revised contract, Russia's Ministry of Atomic Energy has assumed overall management of the project.

"Bushehr is a very interesting and profitable contract for us," said Mr. Nigmatulin, the Russian atomic energy official. "And at the same time it is helping us to restore our industrial capacity."

Having failed to persuade Russia to pull out of Bushehr, Mr. Clinton's senior national security advisers in late 1997 began a campaign to force Ukraine out of the deal. Ukraine's ambassador to Washington at the time, Yuri Shcherbak, was told that the administration would prevent Ukraine from purchasing fuel for its aging nuclear reactors from American companies unless Turboatom gave up the Iran project.

There were carrots as well sticks, the Kharkiv Initiative among the carrots, along with promises of Ukrainian participation in space exploration.

But Turboatom's departure has brought little cheer to Ukraine's industries, which still have connections with Russia's industrial structure. And as a consequence of Turboatom's withdrawal, it seems less likely that Ukraine will be invited to take part in Russian projects to build nuclear power stations in China and India.

"Kharkiv lost a very good order, and that is a shame," said Mr. Nigmatulin, the Russian official. "An order like this represents the revival of the turbine business."

But not for Ukraine.