Special War involves the application of less kinetic and overt forms of power, especially espionage, covert action, and propaganda, to achieve national aims. As I’ve explained, this is something at which the American government, particularly our Department of Defense, does not excel, while unfortunately the Russians do.

My discussion of Special War became a minor meme and has entered the lexicon of strategy talk, which ought to stimulate a necessary debate, but there’s no evidence yet that anybody in Washington, DC, has thought hard about how to systematically get better in these dark arts.

In recent months we’ve had a public demonstration of the Kremlin’s acumen in Special War, above all with the near-bloodless seizure of Crimea by Moscow’s “little green men,” while lately Ukraine has been subjected to the full covert arsenal of Russia’s military intelligence, GRU: spying, subversion, agitprop, and terrorism, much of it executed through cut-outs and proxies.

Although the Kremlin’s efforts to subdue Ukraine without invasion are faltering -- Putin seems to have grown recklessly overconfident after his Crimean victory and underestimated Kyiv’s resolve -- there is no doubt that Moscow’s Special War has rendered sterling service in espionage and propaganda, including in the West.

It’s important to note that the Kremlin’s Special War is waged against the West in toto, not just Ukraine. For Putin to achieve his easily decipherable strategic aims -- dividing NATO and bringing the European Union to heel while keeping the United States on the margins, thereby assuring Moscow’s free hand in Eastern Europe and restoring Russian greatness -- he must demoralize and divide those in Europe who seek to challenge rebounding Russian influence in Europe and hegemony in the East. This is where the Kremlin’s powerful intelligence agencies, what they call the “special services,” come into play.

As I’ve discussed previously, Russian espionage against the West is at an all-time high, equal to if not exceeding Cold War levels. In many Western countries, GRU and its civilian counterpart, the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), have at least as many intelligence officers posted as the Soviets ever did. States that are members of NATO and the EU are of particular interest to Moscow as it seeks to divide alliances and conquer without fighting.

No European country better illustrates how Russia wages Special War than Hungary, which is a member of both NATO and the EU. Russian intelligence is highly active in Hungary, as I’ve explained before, with its agents burrowed deep into politics, the security sector, and the economy.

I recently wrote about the consternation of French intelligence that the Russian company Rosatom sold a nuclear reactor to another European country because the SVR had been secretly informed about the offer made by its French competitor, Areva. That country was Hungary. Budapest has a strategic counterintelligence problem on its hands that it is unlikely to defeat on its own.

Neither is it evident that Budapest possesses the political will to seriously confront this covert threat from Moscow. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, in power since 2010, has led his ruling Fidesz party down an increasingly Putinesque road, while Orbán’s admiration for the Russian leader is undisguised.

Not only has the current government forged close economic ties with Russia, Orbán speaks respectfully about Putin, while a recent speech the prime minister gave which denounced liberalism and the existing European democratic model, while holding up Russia as an “illiberal” model worthy of emulation, caused shock across the EU. Although Orbán was castigating Western (neo)liberal economics more than democracy, per se, this was cold comfort as it’s evident that Putinphilia is in fashion in Budpest’s power circles.

While many in the West have registered their displeasure with Orbán and his throwback nationalist ways, and some have wondered if Hungary is something of a Russophilic Trojan Horse inside NATO and the EU, the alarming fact is that Fidesz is not a particularly right-wing party by current Hungarian standards. While Orbán possesses a strong parliamentary majority, it bears observing that the opposition is far to his right, and there lies the real concern -- and Moscow’s opportunity.

In April, second place in Hungary’s national elections was taken by the far-right party Jobbik, which secured twenty-one percent of the vote and twenty-five seats in parliament. Founded in 2003, Jobbik (which means “better”*) is an unapologetically radical nationalist party that despises the EU and espouses overt anti-Semitism.

While Jobbik’s particular bugbear is Hungary’s Roma population, which it has unpleasant plans for should the party ever come to power, Jobbik’s dislike of Israel and Jews isn’t something they seek to hide. In a typical case, Krisztina Morvai, Jobbik’s top female politico, suggested that Hungarian Jews who don’t like her or her party masturbate with “their tiny circumcised dicks.” In more-Putin-than-Putin fashion, Jobbik aggressively espouses traditional values and strongly dislikes gays.

The party’s youthful leader, Gábor Vona, who has led Jobbik since 2006, is prone to radical and sometimes downright odd statements, including praising Islam and espousing considerable Turcophilia in addition to his admiration for Putin’s Russia. (Affection for Turkey, whom they view as ethnic kin, has been a trope among Hungarian ultra-nationalists for over a century.) Vona’s comments about Iran are customarily warm also, as Jobbik sees Tehran as an ally against the World Zionist Conspiracy.

Of greatest concern to NATO and the EU, however, are Jobbik’s views regarding most of Hungary’s neighbors. The party espouses open irredentism against nearly all neighboring states, where large Hungarian minorities are present. After World War One, no defeated power suffered greater territorial losses than Budapest.

The Allied-imposed Treaty of Trianon deprived Hungary of the majority of its territory and population, while leaving nearly a third of all Magyars (i.e. ethnic Hungarians) outside the borders of much-truncated Hungary. There remain large Magyar populations in neighboring states, including over 150,000 in Ukraine, more than a quarter-million in Serbia (specifically Vojvodina), some 460,000 in Slovakia, and above all more than 1.2 million Magyars in Romania.

Most Hungarians continue to view Trianon as an injustice, while Magyar right-wingers have foamed at the mouth about it for nearly a century. Prime Minister Orbán has not been above playing the nationalist card, hinting at possible revisions to Trianon, causing alarm in the Danubian basin, but Jobbik goes considerably further.

The party has frequently called for border revisions, leading to significant tensions with Romania and Slovakia, both of which are fellow members of NATO and the EU. While Fidesz exploits the Trianon issue every once in a while to score points with Hungarian nationalists, few think Orbán takes the issue seriously, while on the matter of its co-nationals outside Hungary Jobbik seems to be deadly earnest.

Then there is the troubling question of foreign support for Jobbik. Many believe the party has taken secret funds from Tehran, but that has yet to be proved, while Jobbik’s close ties to Moscow are no longer a matter of conjecture. In May, Hungary’s Parliamentary National Security Committee accused Béla Kovács, a leading Jobbik player and a member of the European Parliament (MEP), of being an active Russian spy.

Although he was short of funds for years after his salad bar restaurant failed, Kovács by 2010 was flush with cash, leading to questions about the origin of his wealth. This may have something to do with Kovács’s regular clandestine meetings with Russian case officers that Hungarian counterintelligence uncovered.

Kovács lived for several years in Russia and made no efforts to disguise his deep admiration for that country and Vladimir Putin. He was an agent hiding in plain sight. In Brussels, as an MEP, Kovács was widely considered to be more a lobbyist for Moscow than for Budapest.

Significantly, Kovács also serves as the President of the Alliance of European National Movements, an umbrella group of far-right parties across the EU, several of which are believed to be on the Kremlin payroll. Kovács protested his innocence of any espionage, and Jobbik brushed off accusations of secret Moscow ties, but the Hungarian media was generally skeptical, calling the suspect “KGBéla” -- the nickname by which he was known inside his own party!

It is widely suspected that Kovács is not the only Jobbik higher-up to be secretly working for Moscow. Party leader Gábor Vona has made trips to Russia, palling around with leading Kremlin ideologist and ultra-nationalist Aleksandr Dugin.

Former Jobbik members have stated that Vona is actually a Kremlin agent, while the Budapest media wondered about the Jobbik’s head’s curious comment in January: “masses of our sleeping agents await our victory in state administration. They are still wary of showing their support in public, but we can count on them when the time comes.” More than a few Hungarian patriots have looked at Jobbik and determined that it is not an actual nationalist party, rather a fake one in the pay of Moscow.

This background inevitably raises questions about some of Jobbik’s recent actions. The party has fully taken Moscow’s side in the Ukraine crisis, denouncing the government in Kyiv as “chauvinistic and illegitimate,” while Jobbik has also encouraged ethnic Hungarians in Ukraine not to serve in the military to resist the Russian-directed war in the country’s east.

Jobbik has tried to stir up trouble for Ukraine in the Transcarpathia region, where the country’s Hungarians are, and there have been strange events happening lately near the Hungarian border. Antiwar protests among ethnic Hungarians have become a nuisance in Transcarpathia, where local Hungarian politicians have openly accused Jobbik of fomenting unrest to aid Moscow in its war against Ukraine, a view which is held by Ukrainian intelligence as well.

Last week’s mysterious attack on the headquarters of the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) headquarters building in the border town of Uzhhorod, adjacent to Hungary, by four men in camouflage, has raised more questions still.

Of greatest concern are Jobbik’s recent efforts to stir up serious trouble inside NATO and the EU, particularly with regards to Romania, a critical frontline state for the Atlantic Alliance as its neighbor Ukraine is convulsed by war. Last week, party leader Vona, in a speech that praised Russia and denounced Hungary’s “Euro-Atlantic orientation,” stated that autonomy for Hungarians living in Romania is inevitable, “no matter what the Romanian state might do.”

Needless to add, this provocative statement caused serious concern in Bucharest and has raised tensions between Romania and Hungary, yet again, at a critical time when such disharmony is detrimental to both NATO and the EU.

Cui bono? is the obvious question to be asked here. While Jobbik certainly are Hungarian nationalists who pine for the revision of Trianon -- which most Hungarians understand is a fantasy in any military and political terms -- the timing of the party’s provocations against Ukraine and Romania must be questioned.

Given its known ties with the Kremlin and its intelligence services, one need not be overly suspicious to wonder about who is calling the shots inside Jobbik. This issue matters far beyond Hungary, and with the rise of far-right parties in many European countries, some of whom, like Jobbik, openly admire Putin and his country, all those in the Euro-Atlantic region who think Russia does not represent a positive force for peace should pay attention.

*Its full name is Movement for a Better Hungary (Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom)

This article originally appeared at The XX Committee. Copyright 2014.

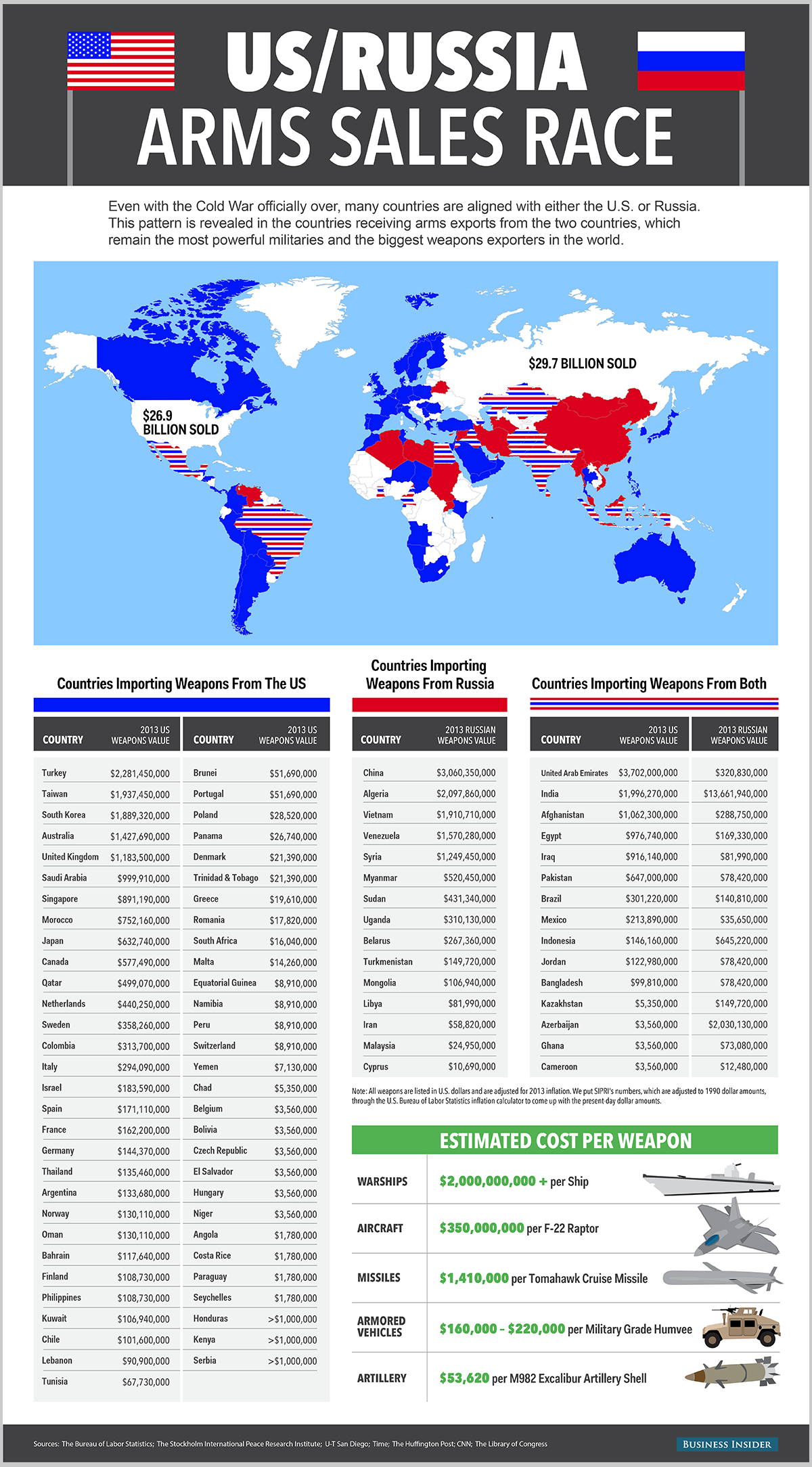

They say the Cold War is over, but Russia and the U.S. remain the leading supplier of weapons to countries around the world and are the two biggest military powers. Lately, tensions have been pretty high, too.

The U.S. supplies much of NATO and Middle Eastern allies like Turkey, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.

Russia supplies other BRIC nations, as well as Iran, much of Southeast Asia, and North Africa.

We took numbers from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute for 2012-2013 to see whom the two rivals were supplying with weaponry. The U.S. dealt to 59 nations that Russia doesn't sell or send weaponry to, while Russia dealt to just 15 nations that don't receive U.S. arms.

Fifteen countries received weaponry from both the U.S. and Russia, including Brazil, India, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

The country that received the highest dollar amount of U.S. weaponry was the United Arab Emirates, with more than $3.7 billion in arms received over that period. Russia dealt the greatest value of weapons to India, sending more than $13.6 billion.

Overall, the U.S. sent more than $26.9 billion in weaponry to foreign nations, while Russia sent weaponry exceeding $29.7 billion in value around the globe.

Interestingly,

the U.S. actually recieved roughly $16 million worth of weaponry from

Russia. This was part of a $1 billion helicopter deal the two nations

made so that the U.S. could supply Afghan security forces with

equipment they

were already more familiar with.

Importantly, SIPRI's totals don't measure the cost of the transaction but the cost of the weapons' production. The numbers are listed as the production value of the weapons sold rather than the amount they were actually sold for. In addition, SIPRI does not track the transfer of certain small arms.

SIPRI gives several examples to explain their chosen method. In 2009, six Eurofighters valued at $55 million each were delivered by Germany to Austria. Therefore the delivery was valued at $330 million, even though the actual transaction likely netted a much higher total. For comparison, when The New York Times listed the total of weapons sold by the U.S. at $66.3 billion in 2011, SIPRI came up with a much lower total based off of production cost of $15.4 billion.

You can read the full explanation of SIPRI's calculations here.