Wizeus

> Religious

Affairs

| Katriuk2012

| Video

Links

| Perfidy

| Book

Reviews

| Putin

Files

| Miscellaneous

>

American Interest | 09Jan2017 | James Henry

http://www.the-american-interest.com/2016/12/19/the-curious-world-of-donald-trumps-private-russian-connections/

The Curious World of

Donald Trump’s

Private Russian Connections

Did the American people really know they were putting such a

“well-connected” guy in the White House?

hroughout Donald Trump’s presidential campaign he expressed

glowing admiration for Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Many of Trump’s

adoring comments were utterly gratuitous. After his Electoral College

victory, Trump continued praising the former head of the KGB while

dismissing the findings of all 17 American national security agencies

that Putin directed Russian government interference to help Trump in

the 2016 American presidential election.As veteran

investigative economist and journalist Jim Henry shows below, a robust

public record helps explain the fealty of Trump and his family to this

murderous autocrat and the network of Russian oligarchs. Putin and his

billionaire friends have plundered the wealth of their own people. They

have also run numerous schemes to defraud governments and investors in

the United States and Europe. From public records, using his renowned

analytical skills, Henry shows what the mainstream news media in the

United States have failed to report in any meaningful way: For three

decades Donald Trump has profited from his connections to the Russian

oligarchs, whose own fortunes depend on their continued fealty to Putin.

We don’t know the full relationship between Donald Trump, the

Trump family and their enterprises with the network of world-class

criminals known as the Russian oligarchs. Henry acknowledges that his

article poses more questions than answers, establishes more connections

than full explanations. But what Henry does show should prompt every

American to rise up in defense of their country to demand a thorough,

out-in-the-open congressional investigation with no holds barred. The

national security of the United States of America and of peace around

the world, especially in Europe, may well depend on how thoroughly we

understand the rich network of relationships between the 45th President

and the Russian oligarchy. When Donald Trump chooses to exercise, or

not exercise, his power to restrain Putin’s drive to invade independent

countries and seize their wealth, as well as loot countries beyond his

control, Americans need to know in whose interest the President is

acting or looking the other way.

-- David Cay

Johnston,

Pulitzer Prize-winning

author of The Making of Donald Trump

“Tell me who you walk with and I’ll tell you who you are.”

-- Cervantes

“I’ve always been blessed with a kind of intuition about people that

allows me to sense who the sleazy guys are, and I stay far away.”

-- Donald Trump, Surviving

at the Top

[W.Z. This article by James Henry supports

my analysis archived in my Zuzak

GRC Report; January 04, 2017 in which I warn of the

establishment of an "overt criminal-corrupt regime headed by Donald

Trump":

In

2016, many of us have watched in disbelief and horror at the political

developments in Ukraine (revanchism of Oligarchic corruption), the

Middle East (the ongoing Syrian refugee crisis overwhelming Turkey and

Europe), Europe (Brexit and the rise of extremist political parties)

and the United States (the election of Donald Trump). The deterioration

of the American political process appears to have accelerated since the

dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, followed by the blossoming of

organized crime and corruption in the post-Soviet space and its

emigration to the United States. It culminated with the 2016

presidential election campaign orchestrated and manipulated by the

political elites of the Democratic and Republican parties. The American

voter was given a choice between a covert corrupt-criminal regime

headed by Hillary Clinton and an overt criminal-corrupt regime headed

by Donald Trump. Will this Presidential election usher in an "era of

epic corruption and contempt for the rule of law" culminating in the

transformation of the United States into a "Trumpistan"? Or will

American patriots, democratic institutions and the checks and balances

represented by the Senate and Congress prevent this occurrence and,

perhaps, reverse recent trends?

Further

evidence of the nefarious connection between Donald Trump and Vladimir

Putin's regime is provided by the United States intelligence services

release of a 25-page pdf report

Background

to "Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US

Elections": The Analytic Process and Cyber Incident Attribution

and the 35-page pdf file of 16 rather sensationalized

Company Intelligence Reports 2016

covering

the period from 20Jun2016 to 13Dec2016 that were presumably compiled by

Christopher Steele, Ex-British Intelligence Officer and released by

Buzzfeed.]

Even before the

November 8, 2016 election, many leading Democrats were vociferously

demanding

that the FBI disclose the fruits of its investigations into

Putin-backed Russian hackers. Instead FBI Director Comey decided to

temporarily revive his zombie-like investigation of Hillary’s emails.

That decision may well have had an important impact on the election,

but it did nothing to resolve the allegations about Putin. Even now,

after the CIA has disclosed an abstract of its own still-secret

investigation, it is fair to say that we still lack the cyberspace

equivalent of a smoking gun.

Fortunately, however, for those of us who are curious about Trump’s

Russian connections, there is another readily accessible body of

material that has so far received surprisingly little attention. This

suggests that whatever the nature of President-elect Donald Trump’s

relationship with President Putin, he has certainly managed to

accumulate direct and indirect connections with a far-flung private

Russian/FSU network of outright mobsters, oligarchs, fraudsters, and

kleptocrats.

Any one of these connections might have occurred at random. But the

overall pattern is a veritable Star Wars bar scene of unsavory

characters, with Donald Trump seated right in the middle. The

analytical challenge is to map this network -- a task that most

journalists and law enforcement agencies, focused on individual cases,

have failed to do.

Of course, to label this network “private” may be a stretch, given that

in Putin’s Russia, even the toughest mobsters learn the hard way to

maintain a respectful relationship with the “New Tsar.” But here the

central question pertains to our new Tsar. Did

the American people really know they were putting such a

“well-connected” guy in the White House?

The

Big Picture: Kleptocracy and

Capital Flight

A few of Donald

Trump’s connections to oligarchs and assorted thugs have already

received sporadic press attention -- for example, former Trump campaign

manager Paul Manafort’s reported relationship with exiled Ukrainian

oligarch Dmytro Firtash. But no one has pulled the connections

together, used them to identify still more relationships, and developed

an image of the overall patterns.

Nor has anyone related these cases to one of the most central facts

about modern Russia: its emergence since the 1990s as a world-class

kleptocracy, second only to China as a source of illicit capital and

criminal loot, with more than $1.3 trillion of net offshore “flight

wealth” as of 2016.1

This tidal wave of illicit capital is hardly just Putin’s doing. It is

in fact a symptom of one of the most epic failures

in modern political economy -- one for which the West bears a great

deal

of responsibility. This is the failure, in the wake of the Soviet

Union’s collapse in the late 1980s, to ensure that Russia acquires the

kind of strong, middle-class-centric economic and political base that

is required for democratic capitalism, the rule of law, and stable,

peaceful relationships with its neighbors.

Instead, from 1992 to the Russian debt crisis of August 1998, the West

in general -- and the U.S. Treasury, USAID, the State Department, the

IMF/World Bank, the EBRD, and many leading economists in

particular -- actively promoted and, indeed, helped to finance one of

the

most massive transfers of public wealth into private hands that the

world has ever seen.

For example, Russia’s 1992 “voucher privatization” program permitted a

tiny elite of former state-owned company managers and party apparatchiks

to acquire control over a vast number of public enterprises,

often with the help of outright mobsters. A majority of Gazprom, the

state energy company that controlled a third of the world’s gas

reserves, was sold for $230 million; Russia’s entire national electric

grid was privatized for $630 million; ZIL, Russia’s largest auto

company, went for about $4 million; ports, ships, oil, iron and steel,

aluminum, much of the high-tech arms and airlines industries, the

world’s largest diamond mines, and most of Russia’s banking system also

went for a song.

In 1994-96, under the infamous “loans-for-shares” program, Russia

privatized 150 state-owned companies for just $12 billion, most of

which was loaned to a handful of well-connected buyers by the state --

and

indirectly by the World Bank and the IMF. The principal

beneficiaries of this “privatization” -- actually,

cartelization -- were initially just 25 or so budding oligarchs with

the

insider connections to buy these properties and the muscle to hold them.2

The happy few who made personal fortunes from this feeding frenzy -- in

a

sense, the very first of the new kleptocrats -- not only included

numerous

Russian officials, but also leading gringo investors/advisers, Harvard

professors, USAID advisers, and bankers at Credit Suisse First Boston

and other Wall Street investment banks. As the renowned development

economist Alex Gerschenkron, an authority on Russian development, once

said, “If we were in Vienna, we would have said, ‘We wish we could play

it on the piano!'”

For the vast majority of ordinary Russian citizens, this extreme

re-concentration of wealth coincided with nothing less than a

full-scale 1930s-type depression, a “shock

therapy”-induced rise in domestic price levels that wiped out the

private savings of millions, rampant lawlessness, a public health

crisis, and a sharp decline in life expectancy and birth rates.

Sadly, this neoliberal “market reform” policy package that was

introduced at a Stalin-like pace from 1992 to late 1998 was not only

condoned but partly designed and financed by senior Clinton

Administration officials, neoliberal economists, and innumerable USAID,

World Bank, and IMF officials. The few dissenting voices included some

of the West’s best economic brains—Nobel laureates like James Tobin,

Kenneth Arrow, Lawrence Klein, and Joseph Stiglitz. They also included

Moscow University’s Sergei Glaziev, who now serves as President Putin’s

chief economic advisor.3 Unfortunately, they

were no match for the folks with the cash.

There was also an important intervention in Russian politics. In

January 1996 a secret team of professional U.S. political consultants

arrived in Moscow to discover that, as CNN put it back then, “The only

thing voters like less than Boris Yeltsin is the prospect of upheaval.”

The experts’ solution was one of earliest “Our brand is crisis”

campaign strategies, in which Yeltsin was “spun” as the only

alternative to “chaos.” To support him, in March 1996 the IMF also

pitched in with $10.1 billion of new loans, on top of $17.3 billion of

IMF/World Bank loans that had already been made.

With all this outside help, plus ample contributions from Russia’s new

elite, Yeltsin went from just 8 percent approval in the January 1996

polls to a 54-41 percent victory over the Communist Party candidate,

Gennady Zyuganov, in the second round of the July 1996 election. At the

time, mainstream media like Time

and the New

York Times were delighted. Very few outside Russia

questioned the wisdom of this blatant intervention in post-Soviet

Russia’s first democratic election, or the West’s right to do it in

order to protect itself.

By the late 1990s the actual chaos that resulted

from Yeltsin’s warped policies had laid the foundations for a strong

counterrevolution, including the rise of ex-KGB officer Putin and a

massive outpouring of oligarchic flight capital that has continued

virtually up to the present. For ordinary Russians, as noted, this was

disastrous. But for many banks, private bankers, hedge funds, law

firms, and accounting firms, for leading oil companies like ExxonMobil

and BP, as well as for needy borrowers like the Trump Organization, the

opportunity to feed on post-Soviet spoils was a godsend. This was

vulture capitalism at its worst.

The nine-lived Trump, in particular, had just suffered a string of six

successive bankruptcies. So the massive illicit outflows from Russia

and oil-rich FSU members like Kazahkstan and Azerbaijan from the

mid-1990s provided precisely the kind of undiscriminating investors

that he needed. These outflows arrived at just the right time to fund

several of Trump’s post-2000 high-risk real estate and casino

ventures -- most of which failed. As Donald Trump, Jr., executive vice

president of development and acquisitions for the Trump Organization, told

the “Bridging U.S. and Emerging Markets Real Estate” conference

in Manhattan in September 2008 (on the basis, he said, of his

own “half dozen trips to Russia in 18 months”):

[I]n terms of high-end product influx into the United

States, Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a

lot of our assets; say in Dubai, and certainly with our project in SoHo

and anywhere in New York. We see a lot of money pouring in from Russia.

All this helps to explain one of the most intriguing puzzles

about Donald Trump’s long, turbulent business career: how he managed to

keep financing it, despite a dismal track record of failed projects.4

According to the “official story,” this was simply due to a combination

of brilliant deal-making, Trump’s gold-plated brand, and raw animal

spirits -- with $916

million of creative tax dodging as a kicker. But this

official story is hokum. The truth is that, since the late 1990s, Trump

was also greatly assisted by these abundant new sources of global

finance, especially from “submerging markets” like Russia.

This suggests that neither Trump nor Putin is an “uncaused cause.” They

are not evil twins, exactly, but they are both byproducts of the same

neoliberal policy scams that were peddled to Russia’s struggling new

democracy.

A

Guided Tour of Trump’s

Russian/FSU Connections\

The following roundup

of Trump’s Russo-Soviet business connections is based on published

sources, interviews with former law enforcement staff and other experts

in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Iceland, searches of

online corporate registries,5 and a detailed

analysis of offshore company data from the Panama Papers.6

Given the sheer scope of Trump’s activities, there are undoubtedly

other worthy cases, but our interest is in overall patterns.

Note that none of the activities and business connections related here

necessarily involved criminal conduct. While several key players do

have criminal records, few of their prolific business dealings have

been thoroughly investigated, and of course they all deserve the

presumption of innocence. Furthermore, several of these players reside

in countries where activities like bribery, tax dodging, and other

financial chicanery are either not illegal or are rarely prosecuted. As

former British Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey once said, the

difference between “legal” and “illegal” is often just “the width of a

prison wall.”

So why spend time collecting and reviewing material that either

doesn’t point to anything illegal or in some cases may even be

impossible to verify? Because, we submit, the mere fact that such

assertions are widely made is of legitimate public interest in its own

right. In other words, when it comes to evaluating the probity of

senior public officials, the public has the right to know about any

material allegations -- true, false, or, most commonly, unprovable --

about

their business partners and associates, so long as this information is

clearly labeled as unverified.

Furthermore, the individual case-based approach to investigations

employed by most investigative journalists and law enforcement often

misses the big picture: the global networks of influence and finance,

licit and illicit, that exist among business people, investors,

kleptocrats, organized criminals, and politicians, as well as the

“enablers” -- banks, accounting firms, law firms, and havens. Any

particular component of these networks might easily disappear without

making any difference. But the networks live on. It is these shadowy

transnational networks that really deserve scrutiny.

Bayrock

Group LLC -- Kazakhstan and

Tevfik Arif

We’ll begin our tour

of Trump’s Russian/FSU connections with several business relationships

that evolved out of the curious case of Bayrock Group LLC, a

spectacularly unsuccessful New York real estate development company

that surfaced in the early 2000s and, by 2014, had all but disappeared

except for a few lawsuits. As of 2007, Bayrock and its partners

reportedly had more than $2 billion of Trump-branded deals in the

works. But most of these either never materialized or were miserable

failures, for reasons that will soon become obvious.

Bayrock’s “white elephants” included the 46-story Trump SoHo

condo-hotel on Spring Street in New York City, for which the principle

developer was a partnership formed by Bayrock and FL Group, an

Icelandic investment company. Completed in 2010, the SoHo soon became

the subject of prolonged civil litigation by disgruntled condo buyers.

The building was foreclosed by creditors and resold in 2014 after more

than $3 million of customer down payments had to be refunded.

Similarly, Bayrock’s Trump International Hotel & Tower in Fort

Lauderdale was foreclosed and resold in 2012, while at least three

other Trump-branded properties in the United States, plus many other

“project concepts” that Bayrock had contemplated, from Istanbul and

Kiev to Moscow and Warsaw, also

never happened.

Carelessness about due diligence with respect to potential partners and

associates is one of Donald Trump’s more

predictable

qualities.

Acting on the seat of the pants, he had hooked up with Bayrock rather

quickly in 2005, becoming an 18 percent minority equity partner in the

Trump SoHo, and agreeing to license his brand and manage the building.7

Exhibit A in the panoply of former Trump business partners is Bayrock’s

former Chairman, Tevfik Arif (aka Arifov), an �migr� from Kazakhstan

who reportedly took up residence in Brooklyn in the 1990s. Trump also

had extensive contacts with another key Bayrock Russian-American from

Brooklyn, Felix Sater (aka Satter), discussed below.8

Trump has lately had some difficulty recalling very much about either

Arif or Sater. But this is hardly surprising, given what

we now know about them. Trump

described his introduction to Bayrock in a 2013 deposition

for a lawsuit that was brought by investors in the Fort Lauderdale

project, one of Trump’s first with Bayrock: “Well, we had a tenant in …

Trump Tower called Bayrock, and Bayrock was interested in getting us

into deals.”9

According to several reports, Tevfik Arif was originally from

Kazakhstan, a Soviet republic until 1992. Born in 1950, Arif worked for

17 years in the Soviet Ministry of Commerce and Trade, serving as

Deputy Director of Hotel Management by the time of the Soviet Union’s

collapse.10 In the early 1990s he relocated to

Turkey, where he reportedly helped

to develop properties for the Rixos Hotel chain. Not long

thereafter he relocated to Brooklyn, founded Bayrock, opened an office

in the Trump Tower, and started to pursue projects with Trump and other

investors.11

Tevfik Arif was not Bayrock’s only connection to Kazakhstan. A 2007

Bayrock investor presentation refers to Alexander Mashevich’s

“Eurasia Group” as a strategic partner for Bayrock’s equity finance.

Together with two other prominent Kazakh billionaires, Patokh Chodiev

(aka “Shodiyev”) and Alijan Ibragimov, Mashkevich reportedly ran

the “Eurasian Natural Resources Cooperation.” In Kazakhstan

these three are sometimes referred to as “the

Trio.”12

The Trio has apparently worked together ever since Gorbachev’s late

1980s perestroika in metals and other natural

resources. It was during this period that they first acquired a

significant degree of control over Kazakhstan’s

vast mineral and gas reserves. Naturally they found it useful

to become friends with Nursultan Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan’s long-time

ruler. Indeed, State

Department cables leaked by Wikileaks in November 2010

describe a close

relationship between “the Trio” and the seemingly-perpetual

Nazarbayev kleptocracy.

In any case, the Trio has recently attracted the attention of many

other investigators and news outlets, including the September

11 Commission Report, the Guardian,

Forbes,

and the Wall

Street Journal. In addition to resource grabbing,

the litany of the Trio’s alleged activities include money

laundering, bribery,

and racketeering.13

In 2005, according to U.S. State Department cables released by

Wikileaks, Chodiev (referred to in a State Department cable as “Fatokh

Shodiyev”) was recorded

on video attending the birthday of reputed Uzbek mob boss

Salim Abduvaliyeva and presenting him with a $10,000 “gift” or

“tribute.”

According to the Belgian newspaper Le Soir,

Chodiev and Mashkevich also became close associates of a curious

Russian-Canadian businessman, Boris

J. Birshtein. who happens to have been the father-in-law of

another key Russian-Canadian business associate of Donald Trump in

Toronto. We will return to Birshtein below.

The Trio also turn up in the April 2016 Panama Papers database as the

apparent beneficial owners of a Cook Islands company, “International

Financial Limited.”14 The Belgian

newspapers Het

Laatste Nieuws, Le Soir, and

La

Libre Belgique have reported that Chodiev paid €23

million to obtain a “Class B” banking license for this same company,

permitting it to make international currency trades. In the words of a

leading Belgian

financial regulator, that would “make all money laundering

undetectable.”

The Panama Papers also indicate that some of Arif’s connections at the

Rixos Hotel Group may have ties to Kazakhstan. For example, one

offshore company listed in the Panama Papers database, “Group

Rixos Hotel,” reportedly acts as an intermediary for four BVI offshore

companies.15 Rixos Hotel’s CEO, Fettah Tamince,

is listed as having been a shareholder for two of these companies,

while a shareholder in another -- “Hazara Asset Management” -- had the

same

name as the son of a recent Kazakhstan Minister for Sports and Tourism.

As of 2012, this Kazakh official was described as the third-most

influential deputy in the country’s Mazhilis (the lower house of

Parliament), in a Forbes-Kazakhstan

article.

According to a 2015 lawsuit against Bayrock by Jody Kriss, one of its

former employees, Bayrock started to receive millions of dollars in

equity contributions in 2004, supposedly by way of Arif’s brother in

Russia, who allegedly “had

access to cash accounts at a chromium refinery in Kazakhstan.”

This as-yet unproven allegation might well just be an attempt by the

plaintiff to extract a more attractive settlement from Bayrock and its

original principals. But it is also consistent with fact that chromium

is indeed one of the Kazakh natural resources that

is reportedly controlled by the Trio.

As for Arif, his most recent visible brush with the law came in 2010,

when he and other members of Bayrock’s Eurasian Trio were arrested

together in Turkey during a police raid on a suspected prostitution

ring, according to the Israeli daily Yediot

Ahronot.

At the time, Turkish investigators reportedly asserted that Arif might

be the head of a criminal organization that was trafficking

in Russian and Ukrainian escorts, allegedly including some as

young as 13.16 According to these assertions,

big-ticket clients were making their selections by way of a modeling

agency website, with Arif allegedly handling the logistics. Especially

galling to Turkish authorities, the preferred

venue was reportedly a yacht that had once belonged to the

widely-revered Turkish leader Atat�rk.

It was also alleged that Arif may have also provided lodging

for young women at Rixos Group hotels.17

According to Russian media, two senior Kazakh officials were also

arrested during this incident, although the Turkish Foreign Ministry

quickly dismissed this allegation as “groundless.”

In the end, all the charges against Arif resulting from this incident

were dismissed in 2012 by Turkish courts, and his spokespeople have

subsequently denied all involvement.

Finally, despite Bayrock’s demise and these other legal entanglements,

Arif has apparently remained active. For example, Bloomberg reports

that, as of 2013, he, his son, and Rixos Hotels’ CEO Fettah Tamince had

partnered to pursue the rather controversial business of advancing

funds to cash-strapped high-profile soccer players in exchange for a

share of their future marketing revenues and team transfer fees. In the

case of Arif and his partners, this new-wave form of indentured

servitude was reportedly

implemented by way of a UK- and Malta-based hedge fund, Doyen

Capital LLP. Because this

practice is subject to innumerable potential abuses,

including the possibility of subjecting athletes or clubs to undue

pressure to sign over valuable rights and fees, UEFA, Europe’s

governing soccer body, wants to ban it. But FIFA, the notorious global

football regulator, has been customarily slow to act. To date, Doyen

Capital LLP has reportedly taken financial gambles on several

well-known players, including the Brazilian star Neymar.

The

Case of Bayrock LLC -- Felix Sater

Our second exhibit is

Felix Sater, the senior Bayrock executive introduced earlier. This is

the fellow who worked at Bayrock from 2002 to 2008 and negotiated

several important deals with the Trump Organization and other

investors. When Trump was asked who at Bayrock had brought him the Fort

Lauderdale project in the 2013 deposition cited above, he replied:

“It could have been Felix Sater, it could have been -- I really don’t

know

who it might have been, but somebody from Bayrock.”18

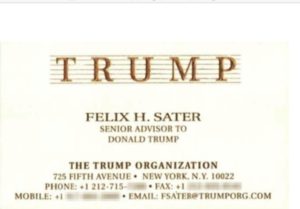

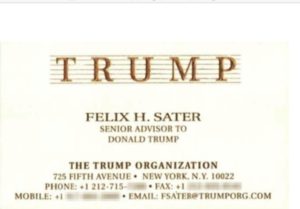

Although Sater left Bayrock in 2008,

by 2010 he was reportedly back in Trump Tower as a “senior advisor” to

the Trump Organization -- at least on his business card --with his own

office in the building.

Sater has also testified under oath that he had escorted Donald Trump,

Jr. and Ivanka Trump around Moscow in 2006, had met frequently with

Donald over several years, and had once flown with him to Colorado. And

although this might easily have been staged, he is also reported

to have visited Trump Tower in July 2016 and made a personal $5,400

contribution to Trump’s campaign.

Whatever Felix Sater has been up to recently, the key point is that by

2002, at the latest,19 Tevfik Arif decided to

hire him as Bayrock’s COO and managing director. This was despite the

fact that by then Felix had already compiled an astonishing

track record as a professional criminal, with multiple felony

pleas and convictions, extensive connections to organized crime,

and -- the ultimate prize -- a virtual “get out of jail free card,”

based on

an informant relationship with the FBI and the CIA that is vaguely

reminiscent of Whitey Bulger.20

Sater, a Brooklyn resident like Arif, was born in Russia in 1966. He reportedly

emigrated with his family to the United States in the mid-1970s and

settled in “Little Odessa.” It seems that his father, Mikhael

Sheferovsky (aka Michael Sater), may have been engaged in Russian mob

activity before he arrived in the United States. According to a

certified U.S. Supreme Court petition, Felix Sater’s FBI handler stated

that he “was well familiar with the crimes of Sater and his (Sater’s)

father, a (Semion) Mogilevich crime syndicate boss.”21

A 1998

FBI report reportedly said Mogilevich’s organization had

“approximately 250 members,” and was involved in trafficking nuclear

materials, weapons, and more, as well as money laundering. (See below.)

But Michael Sater may have been less ambitious than his son. His only reported

U.S. criminal conviction came in 2000, when he pled guilty to

two felony counts for extorting Brooklyn restaurants, grocery stores,

and clinics. He was released with three years’ probation.

Interestingly, the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York

who handled that case at

the time was Loretta

Lynch, who succeeded Eric Holder as U.S. Attorney General in

2014. Back in 2000, she was also overseeing a budding informant

relationship and a plea bargain with Michael’s son Felix, which may

help to explain the father’s sentence.

By then young Felix Sater was already well on his way to a career as a

prototypical Russian-American mobster. In 1991 he stabbed

a commodity trader in the face with a margarita glass stem in

a Manhattan bar, severing

a nerve. He was convicted of a felony and sent

to prison. As Trump

tells it, Sater simply “got into a barroom fight, which a lot

of people do.” The sentence for this felony conviction could not have

been very long, because, by 1993, 27-year-old Felix was already a

trader in a brand new Brooklyn-based commodity firm called “White Rock

Partners,” an innovative joint venture among four New York crime

families and the Russian mob aimed at bringing state-of-the art

financial fraud to Wall Street.

Five years later, in

1998, Felix Sater pled guilty to stock racketeering, as one

of 19 U.S.-and Russian mob-connected traders who participated in a $40

million “pump and dump” securities fraud scheme. Facing

twenty years in Federal prison, Sater and Gennady Klotsman, a fellow

Russian-American who’d been with him on the night of the Manhattan bar

fight, turned “snitch” and helped the Department of Justice prosecute

their co-conspirators.22 Reportedly, so

did Salvatore Lauria, another “trader” involved in the

scheme. According to the Jody Kriss lawsuit, Lauria later joined

Bayrock as an off-the-books paid “consultant.” Initially their

cooperation, which lasted from 1998 until at least late 2001, was kept

secret, until it was inadvertently revealed in a March 2000 press

release by U.S. Attorney Lynch.

Unfortunately for Sater, about the same time the NYPD also reportedly

discovered that he had been running a money-laundering scheme and

illicit gun sales out of a Manhattan storage locker. He and Klotsman fled

to Russia. However, according to the New York Times,

which cited Klotsman and Lauria, soon after the events of

September 11, 2001, the ever-creative Sater succeeded in brokering

information about the black market for Stinger

anti-aircraft missiles to the CIA and the FBI. According to

Klotsman, this strategy “bought Felix his freedom,” allowing him to

return to Brooklyn. It is still not clear precisely what information

Sater actually provided, but in 2015 U.S. Attorney General Loretta

Lynch publicly commended him for sharing information that she described

as “crucial

to national security.”

Meanwhile, Sater’s sentence for his financial crimes continued to be

deferred even after his official cooperation in that case ceased in

late 2001. His files remained sealed, and he managed to avoid any

sentencing for those crimes at all until October 23, 2009. When he

finally appeared before the Eastern District’s Judge I. Leo Glasser,

Felix received a $25,000 fine, no jail time, and no probation in a

quiet proceeding that attracted no press attention. Some compared this

sentence to Judge Glasser’s earlier sentence of Mafia hit man “Sammy

the Bull” Gravano to 4.5 years for 19 murders, in exchange for “cooperating

against John Gotti.”

In any case, between 2002 and 2008, when Felix Sater finally left

Bayrock LLC, and well beyond, his ability to avoid jail and conceal his

criminal roots enabled him to enjoy a lucrative new career as Bayrock’s

chief operating officer. In that position, he was in charge of

negotiating aggressive property deals all over the planet, even

while -- according to lawsuits by former Bayrock investors -- engaging

in

still more financial fraud. The only apparent difference was that he

changed his name from “Sater” to “Satter.”23

In the 2013 deposition cited earlier, Trump went on to say “I don’t see

Felix as being a member of the Mafia.” Asked if he had any evidence for

this claim, Trump

conceded “I have none.”24

As for Sater’s pal Klotsman, the past few years have not been kind. As

of December 2016 he is in a Russian penal colony, working off a

ten-year sentence for a failed $2.8 million Moscow diamond heist in

August 2010. In 2016 Klotsman was reportedly placed on a “top-ten list”

of Americans that the Russians were willing to exchange for high-value

Russian prisoners in U.S. custody, like the infamous

arms dealer Viktor Bout. So far there have been no takers.

But with Donald Trump as President, who knows?

The

Case of Iceland’s FL Group

One of the most

serious frauds alleged in the recent Bayrock lawsuit involves FL Group,

an Icelandic private investment fund that is really a saga all its own.

Iceland is not usually thought of as a major offshore financial center.

It is a small snowy island in the North Atlantic, closer to Greenland

than to the UK or Europe, with only 330,000 citizens and a total GDP of

just $17 billion. Twenty years ago, its main exports were cod and

aluminum -- with the imported bauxite smelted there to take advantage

of

the island’s low electricity costs.

But in the 1990s Iceland’s tiny neoliberal political elite had what

they all told themselves was a brilliant idea: “Let’s privatize our

state-owned banks, deregulate capital markets, and turn them loose on

the world!” By the time all three of the resulting privatized banks, as

well as FL Group, failed in 2008, the combined bank loan portfolio

amounted to more than 12.5 times Iceland’s GDP -- the highest country

debt

ratio in the entire world.

For purposes of our story, the most interesting thing about Iceland is

that, long before this crisis hit and utterly bankrupted FL Group, our

two key Russian/FSU/Brooklyn mobster-mavens, Arif and Sater, had

somehow stumbled on this obscure Iceland fund. Indeed, in early 2007

they persuaded FL Group to invest $50 million in a project to build the

Trump SoHo in mid-town Manhattan.

According to the Kriss

lawsuit, at the same time, FL Group and Bayrock’s Felix Sater

also agreed in principle to pursue up to an additional $2 billion in

other Trump-related deals. The Kriss lawsuit further alleges that FL

Group (FLG) also agreed to work with Bayrock to facilitate outright tax

fraud on more than $250 million of potential earnings. In particular,

it alleges that FLG agreed to provide the $50 million in exchange for a

62 percent stake in the four Bayrock Trump projects, but Bayrock would

structure the contract as a “loan.” This meant that Bayrock would not

have to pay taxes on the initial proceeds, while FLG’s anticipated $250

million of dividends would be channeled through a Delaware company and

characterized as “interest payments,” allowing Bayrock to avoid up to

$100 million in taxes. For tax purposes, Bayrock would pretend that

their actual partner was a Delaware partnership that it had formed with

FLG, “FLG Property I LLC,” rather than FLG itself.

The Trump Organization has denied any involvement with FLG. However, as

an equity partner in the Trump SoHo, with a significant 18 percent

equity stake in this one deal alone, Donald Trump himself had to sign

off on the Bayrock-FLG deal.

This raises many questions. Most of these will have to await the

outcome of the Kriss litigation, which might well take years,

especially now that Trump is President. But several of these questions

just leap off the page.

First, how much did President-elect Trump know about the partners and

the inner workings of this deal? After all, he had a significant equity

stake in it, unlike many of his “brand-name only” deals, and it was

also supposed to finance several of his most important East Coast

properties.

Second, how did the FL Group and Bayrock come together to do this dodgy

deal in the first place? One former FL Group manager alleges that the

deal arrived by accident, a “relatively small deal” was nothing special

on either side.25 The Kriss lawsuit, on the

other hand, alleges that FLG was a well-known source of easy money from

dodgy sources like Kazakhstan and Russia, and that other Bayrock

players with criminal histories -- like Salvatore Lauria, for example

-- were

involved in making the introductions.

At this stage the evidence with respect to this second question is

incomplete. But there are already some interesting indications that FL

Group’s willingness to generously finance Bayrock’s peculiar

Russian/FSU/Brooklyn team, its rather poorly-conceived Trump projects,

and its purported tax dodging were not simply due to Icelandic

backwardness. There is much more for us to know about Iceland’s

“special” relationship with Russian finance. In this regard, there are

several puzzles to be resolved.

First, it turns out that FL Group, Iceland’s largest private investment

fund until it crashed in 2008, had several owners/investors with deep

Russian business connections, including several key investors in all

three top Iceland banks.

Second, it turns out that FL Group had constructed an incredible maze

of cross-shareholding, lending, and cross-derivatives relationships

with all these major banks, as illustrated by the following snapshot of

cross-shareholding among Iceland’s financial institutions and companies

as of 2008.26

Cross-shareholding

Relationships, FLG and Other Leading Icelandic Financial Institutions,

2008

This thicket of cross-dealing made it almost impossible

to regulate “control fraud,” where insiders at leading financial

institutions went on a self-serving binge, borrowing and lending to

finance risky investments of all kinds. It became difficult to

determine which institutions were net borrowers or investors, as the

concentration of ownership and self-dealing in the financial system

just soared.

Third, FL Group make a variety of peculiar loans to

Russian-connected

oligarchs as well as to Bayrock. For example, as discussed below, Alex

Shnaider, the Russian-Canadian billionaire who later became Donald

Trump’s Toronto business partner, secured a €45.8 million loan to buy a

yacht from Kaupthing Bank during the same period, while a company

belonging to another Russian billionaire who reportedly owns an

important vodka franchise got an even larger loan.27

Fourth, Iceland’s largest banks also made a series of extraordinary

loans to Russian interests during the run-up to the 2008 crisis. For

example, one of Russia’s wealthiest oligarchs, a close friend of

President Putin, nearly managed to secure at least €400 million (or,

some say, up to four times that much) from Kaupthing,

Iceland’s largest bank, in late September 2008, just as the financial

crisis was breaking wide open. This bank also had important direct and

indirect investments in FL Group. Indeed, until December 2006, it is

reported to have employed the FL Group private equity manager who

allegedly negotiated Felix Sater’s $50 million deal in early 2007.28

Fifth, there are unconfirmed accounts of a secret U.S. Federal Reserve

report that unnamed Iceland banks were being used for Russian money

laundering.29 Furthermore, Kaupthing Bank’s

repeated requests to open a New York branch in 2007-08 were rejected by

the Fed. Similar unconfirmed rumors repeatedly appeared in Danish and

German publications, as did allegations about the supposed Kazakh

origins of FLG’s cash to be “laundered” in the Kriss lawsuit.

Sixth, there is the peculiar fact that, when Iceland’s banks went

belly-up in October 2008, their private banking subsidiaries in

Luxembourg, which were managing at least €8 billion of private assets,

were suddenly seized by Luxembourg banking authorities and transferred

to a new bank, Banque Havilland. This happened so fast that Iceland’s

Central Bank was prevented from learning anything about the identities

or portfolio sizes of the Iceland banks’ private offshore clients. But

again, there were rumors of some important Russian names.

Finally, there is the rather odd phone call that Russia’s Ambassador to

Iceland made to Iceland’s Prime Minister at 6:45 a.m. on October 7,

2008, the day after the financial crisis hit Iceland. According to the

PM’s own account, the Russian Ambassador informed him that then-Prime

Minister Putin was willing to consider offering Iceland a €4

billion Russian bailout.

Of course this alleged Putin offer was modified not long thereafter

into a willingness to entertain an Icelandic negotiating team

in Moscow. By the time the Iceland team got to Moscow later that year,

Russia’s desire to lend had cooled, and Iceland ended up

accepting a $2.1 billion IMF “stabilization

package” instead. But according to a member of the

negotiating team, the reasons for the reversal are still a mystery.

Perhaps Putin had reconsidered because he simply decided that Russia

had to worry about its own considerable financial problems. Or perhaps

he had discovered that Iceland’s banks had indeed been very generous to

Russian interests on the lending side, while -- given Luxembourg’s

actions -- any Russian private wealth invested in Icelandic banks was

already safe.

On the other hand, there may be a simpler explanation for Iceland’s

peculiar generosity to sketchy partners like Bayrock. After all, right

up to the last minute before the October 2008 meltdown, the whole world

had awarded Iceland AAA ratings: Depositors queued up in London to open

high-yield Iceland bank accounts, its bank stocks were booming, and the

compensation paid to its financiers was off the charts. So why would

anyone worry about making a few more dubious deals?

Overall, therefore, with respect to these odd “Russia-Iceland”

connections, the proverbial jury is still out. But all these Icelandic

puzzles are intriguing and bear further investigation.

The

Case of the Trump Toronto Tower

and Hotel -- Alex Shnaider

Our fourth case study

of Trump’s business associates concerns the 48-year-old

Russian-Canadian billionaire Alex

Shnaider, who co-financed the seventy-story Trump Tower and Hotel,

Canada’s tallest building. It opened in Toronto in 2012. Unfortunately,

like so many of Trump’s other Russia/FSU-financed projects, this massive

Toronto condo-hotel project went belly-up this November and

has now entered foreclosure.

According to an online

profile of Shnaider by a Ukrainian news agency, Alex Shnaider

was born in Leningrad in 1968, the son of “Евсей Шнайдер,” or “Evsei

Shnaider” in Russian.30 A recent

Forbes article says that he and his

family emigrated to Israel from Russia when he was four and then

relocated to Toronto when he was 13-14. The Ukrainian news agency says

that Alex’s familly soon established “one of the most successful

stories in Toronto’s Russian quarter, “ and that young Alex, with “an

entrepreneurial streak,” “helped

his father Evsei Shnaider in the business, placing goods on

the shelves and wiping floors.”

Eventually that proved to be a great decision -- Shnaider prospered in

the

New World. Much of this was no doubt due to raw talent. But it also

appears that for a time he got significant helping hand from

his (now

reportedly ex-) father-in-law, another colorful Russian-Canadian, Boris

J. Birshtein.

Originally from Lithuania, Birshtein, now about 69, has been a Canadian

citizen since at least 1982.31 He resided in

Zurich for a time in the early 1990s, but then returned to Toronto and

New York.32 One of his key companies was called

Seabeco SA, a “trading” company that was registered in Zurich in

December 1982.33 By the early 1990s Birshtein

and his partners had started many other Seabeco-related companies in a

wide variety of locations, inclding Antwerp,34

Toronto,35 Winnipeg,36

Moscow, Delaware,37 Panama,38

and Zurich.39 Several of these are still active.40

He often staffed them with directors and officers from a far-flung

network of Russians, emissaries from other FSU countries like

Kyrgyzstan and Moldova, and recent Russia/FSU emigres to

Canada.41

According to the Financial Times and the FBI, in

addition to running Seabeco, Birshtein was a close business associate of Sergei

Mikhaylov, the reputed head of Solntsevskaya

Bratva, the Russian mob’s largest branch, and the world’s

highest-grossing organized crime group as of 2014, according to Fortune.42

A 1996 FBI intelligence report cited by the FT

claims that Birshtein hosted a meeting in his Tel Aviv office for

Mikhaylov, the Ukrainian-born Semion Mogilevich, and several other

leaders of the Russo/FSU mafia, in order to discuss “sharing interests

in Ukraine.”43 A subsequent 1998 FBI

Intelligence report on the “Semion Mogilevich Organization” repeated

the same charge,44 and described Mogilevich’s

successful attempts at gaining control over Ukraine privatization

assets. The FT article also described

how Birshtein and his associates had acquired extraordinary influence

with key Ukraine officials, including President Leonid Kuchma, with the

help of up to $5 million of payoffs.45 Citing

Swiss and Belgian investigators, the FT also

claimed that Birshtein and Mikhaylov jointly controlled a Belgian

company called MAB International in the early 1990s.46

During that period, those same investigators

reportedly observed transfers worth millions of dollars

between accounts held by Mikhaylov, Birshtein, and Alexander Volkov,

Seabeco’s representative in Ukraine.

In 1993, the Yeltsin government reportedly accused Birshtein of illegally

exporting seven million tons of Russian oil and laundering

the proceeds.47 Dmytro Iakoubovski, a former

associate of Birshtein’s who had also moved to Toronto, was said to be

cooperating with the Russian investigation. One night a gunman fired

three shots into Iakoubovski’s home, leaving a note warning him to

cease his cooperation, according to a

New York Times article published that

year. As noted above, according to the Belgian newspaper Le

Soir, two

members of Bayrock’s Eurasian Trio were also involved in

Seabeco during this period as well -- Patokh Chodiev and Alexander

Mashkevich. Chodiev reportedly first met Birshtein through the Soviet

Foreign Ministry, and then went on to run Seabeco’s Moscow office

before joining its Belgium office in 1991. Le Soir

further claims that Mashkevich worked for Seabeco too, and that this

was actually how he and Chodiev had first met.

All this is fascinating, but what about the connections between

Birshtein and Trump’s Toronto business associate, Alex Shnaider? Again,

the leads we have are tantalizing.The Toronto

Globe and Mail reported that in 1991, while enrolled in law

school, young Alex Shnaider started working for Birshtein at Seabeco’s

Zurich headquarters, where he was reportedly introduced to steel

trading. Evidently this was much more than just a job; the Zurich

company registry lists “Alex Shnaider” as a director of “Seabeco Metals

AG” from March 1993 to January 1994.48

In 1994, according

to this account, he reportedly left Seabeco in January 1994

to start his own trading company in Antwerp, in partnership with a

Belgian trader-partner. Curiously, Le

Soir also says that Mikhaylov and Birshtein co-founded MAB

International in Antwerp in January 1994. Is it far-fetched to suspect

that Alex Shnaider and mob boss Mikhaylov might have crossed paths,

since they were both in the same city and they were both close to

Shnaider’s father-in-law?

According to Forbes, soon after Shnaider moved to

Antwerp, he started visiting

the factories of his steel trading partners in Ukraine.49

His favorite client was the Zaporizhstal

steel mill, Ukraine’s fourth largest. At the Zaporizhstal

mill he reportedly met Eduard Shifrin (aka Shyfrin), a metals trader

with a doctorate in metallurgical engineering. Together they

founded Midland Resource Holdings Ltd. in 1994.50

As the Forbes piece argues, with privatization

sweeping Eastern Europe, private investors were jockeying to buy up the

government’s shares in Zaporizhstal. But most traders lacked the

financial backing and political connectons to accumulate large risky

positions. Shnaider and Shifrin, in contrast, started buying up shares

without limit, as if their pockets and connections were very deep. By

2001 they had purchased 93 percent of the plant for about $70 million,

a stake that would be worth much more just five years later, when

Shnaider reportedly turned down a $1.2 billion offer.

Today, Midland Resources Holdings Ltd. reportedly generates more than

$4 billion a year of revenue and has numerous subsidiaries all across

Eastern Europe.51 Shnaider also reportedly

owns Talon International Development, the firm that oversaw

construction of the Trump hotel-tower in Toronto. All this wealth

apparently helped Iceland’s FL Group decide that it could afford to

extend a €45.8 million loan to Alex Shnaider in 2008 to buy a yacht.52

As of December 2016, a search of the Panama Papers database found no

fewer than 28 offshore companies that have been associated

with “Midland Resources Holding Limited.”53

According to the database, “Midland Resources Holding Limited” was a

shareholder in at least two of these companies, alongside an individual

named “Oleg Sheykhametov.”54 The two companies, Olave

Equities Limited and Colley

International Marketing SA, were both registered and active

in the British Virgin Islands from 2007-10.55 A

Russian restaurateur by that same name reportedly

runs a business owned by two other alleged Solntsevskaya mob

associates, Lev Kvetnoy and Andrei Skoch, both of whom

appear with Sergei Mikhaylov. Of course mere inclusion in such

a group photo is not evidence of wrongdoing. (See the

photo here.) According to Forbes,

Kvetnoy

is the 55th richest person in Russia and Skoch,

now a deputy in the Russian Duma, is the 18th.56

Finally, it is also intriguing to note that Boris Birshtein is also

listed as the President of “ME Moldova Enterprises AG,” a Zurich-based

company” that was founded in November 1992, transferred to the canton

of Schwyz in September 1994, and liquidated and cancelled in January

1999.57 Birshstein was a member of the company’s

board of directors from November 1992 to January 1994, when he became

its President. At that point he was succeeded as President in June 1994

by one “Evsei Shnaider, Canadian citizen, resident in Zurich,” who was

also listed as director of the company in September 1994.58

“Evsei Schnaider” is also listed in the Panama registry as a Treasurer

and Director of “The Seabeco Group Inc.,” formed on December 6, 1991,59

and as treasurer and director of Seabeco Security International Inc.,”

formed on December 10, 1991. As of December 2016, both companies are

still in existence.60 Boris Birshtein is listed

as president and director of both companies.61

The

Case of Paul Manafort’s

Ukrainian Oligarchs

Our fifth Trump

associate profile concerns the Russo/Ukrainian connections of Paul

Manafort, the former Washington lobbyist who served as Donald

Trump’s

national campaign director from April 2016 to August 2016.

Manafort’s partner, Rick Davis, also served as national

campaign manager for Senator John McCain in 2008, so this may

not just be a Trump association.

One of Manafort’s biggest clients was the dubious pro-Russian Ukrainian

billionaire Dmytro Firtash. By his own admission, Firtash maintains

strong ties with a recurrent figure on this scene, the

reputed Ukrainian/Russian mob boss Semion Mogilevich. His

most important other links are almost certainly to Putin. Otherwise it

is difficult to explain how this former

used-car salesman could gain a lock on trading goods for gas

in Turkmenistan and also become a lynchpin investor in the Swiss

company RosUrEnergo, which controls Gazprom’s gas sales to Europe.62

In 2008, Manafort teamed up with a former manager of the Trump

Organization to purchase the Drake Hotel in New York for up to $850

million, with Firtash agreeing to invest $112 million. According to a lawsuit

brought against Manafort and Firtash, the key point of the

deal was not to make a carefully-planned investment in real estate, but

to simply launder part of the huge profits that Firtash had skimmed

while brokering dodgy natural gas deals between Russia and Ukraine,

with Mogilevich acting as a “silent

partner.”

Ultimately Firtash pulled out of this Drake Hotel deal. The reasons are

unclear—it has been suggested that he needed to focus on the 2015

collapse and nationalization of his Group DF’s Bank Nadra back home in

Ukraine.63 But it certainly doesn’t appear to

have changed his behavior. Since 2014 there has been a spate

of other Firtash-related prosecutions, with the United States

trying to extradict from Austria in order to stand trial on

allegations that his vast spidernet “Group DF” had bribed Indian

officials to secure mining licenses. The Austrian court has required

him to put up a record-busting €125 million bail while he

awaits a decision.64 And just last

month, Spain has also tried to extradite Firtash on a separate money

laundering case, involving the

laundering of €10 million through Spanish property

investments.

After Firtash pulled out of the deal, Manafort reportedly turned to

Trump, but he declined

to engage. Manafort stepped down as Trump’s campaign manager

in August of 2016 in response to press investigations into his ties not

only to Firtash, but to Ukraine’s previous pro-Russian Yanukovych

government, which had been deposed by a uprising in 2014. However,

following the November 8 election, Manafort reportedly returned

to advise Trump on staffing his new administration. He got an assist

from Putin -- on November 30, 2016 a spokeswoman for the Russian

Foreign

Ministry accused

Ukraine of leaking stories about Manafort in an effort to hurt Trump.

The

Case of “Well-Connected”

Russia/FSU Mobsters

Finally, several other

interesting Russian/FSU connections have a more residential flavor, but

they are a source of very important leads about the Trump network.

Indeed, partly because it has no prying co-op board, Trump Tower in New

York has received

press attention for including among its many honest residents

tax-dodgers, bribers, arms dealers, convicted cocaine traffickers, and

corrupt former FIFA officials.65

One typical example involves the alleged Russian mobster Anatoly

Golubchik, who went to prison in 2014 for running an illegal

gambling ring out of Trump Tower -- not only the headquarters

of

the Trump Organization but also the former headquarters of Bayrock

Group LLC. This operation reportedly took up the entire

51st floor. Also reportedly involved in it was the alleged

mobster Alimzhan

Tokhtakhounov,66 who has the

distinction of making the Forbes 2008 list of the

World’s

Ten Most Wanted Criminals, and whose organization the FBI

believes to be tied

to Mogilevich’s. Even as this gambling ring was still

operating in Trump Tower, Tokhtakhounov reportedly

travelled to Moscow to attend Donald Trump’s 2013 Miss

Universe contest as a special VIP.

In the Panama Papers database we do find the name “Anatoly

Golubchik.” Interestingly, his particular offshore company,

“Lytton Ventures Inc.,”67 shares a corporate

director, Stanley Williams, with a company that may well be connected

to our old friend Semion Mogilevich, the Russian mafia’s alleged “Boss

of Bosses” who appeared so frequently in the story above. Thus Lytton

Ventures Inc. shares this particular director with another company that

is held under the name of “Galina Telesh.”68

According to the Organized

Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, multiple offshore

companies belonging to Semion Mogilevich have been registered under

this same name -- which just happens to be that of Mogilevich’s first

wife.

A 2003 indictment of Mogilevich also mentions two offshore companies

that he is said to have owned, with names that include the terms

“Arbat” and “Arigon.” The same corporate director shared by Golubchik

and Telesh also happens to be a director of a company called Westix

Ltd.,69 which shares its Moscow address with

“Arigon Overseas” and “Arbat Capital.”70 And

another company with that same director appears to belong to Dariga

Nazarbayeva, the eldest daughter of Nursultan Nazarbayev, the

long-lived President of Kazakhstan. Dariga is expected to take

his place if he ever decides to leave office or proves to be

mortal.

Lastly, Dmytro Firtash -- the Mogilevich pal and Manafort client that

we

met earlier -- also turns up in the Panama Papers database as part of

Galina Telesh’s network neighborhood. A director of Telesh’s “Barlow

Investing,” Vasliki Andreou, was also a nominee director of a Cyprus

company called “Toromont

Ltd.,” while another Toromont Ltd. nominee director, Annex

Holdings Ltd., a St. Kitts company, is also listed as a

shareholder in Firtash’s Group DF Ltd., along with Firtash himself.71

And Group

DF’s CEO, who allegedly worked with Manafort to channel

Firtash’s funding into the Drake Hotel venture, is also listed in the

Panama Papers database as a Group DF shareholder. Moreover, a 2006

Financial Times investigation identified

three other offshore companies that are linked to both Firtash and

Telesh.72

Anatoly Golubchik’s Panama

Papers Network Neighborhood

Of course, all of these curious relationships may just be

meaningless coincidences. After all, the director shared by Telesh and

Golubchik is also listed in the same role for more than 200 other

companies, and more than a thousand companies besides Arbat Capital and

Arigon Overseas share Westix’s corporate address. In the burgeoning

land of offshore havens and shell-game corporate citizenship, there is

no such thing as overcrowding. The appropriate way to view all this

evidence is to regard it as “Socratic:” raising important unanswered

questions, not providing definite answers.

In any case, returning to Trump’s relationships through Trump Tower,

another odd one involves the 1990s-vintage fraudulent company YBM

Magnex International. YBM, ostensibly a world-class

manufacturer of industrial magnets, was founded indirectly in Newtown,

Bucks County, Pennsylvania in 1995 by the “boss of bosses,” Semion

Mogilevich, Moscow’s “brainy Don.”

This is a fellow with an incredible history, even if only half of what

has been written about him is true.73

Unfortunately, we have to focus here only on the bits that are most

relevant. Born in Kiev, and now a citizen of Israel as well as Ukraine

and Russia, Semion, now seventy, is a lifelong criminal. But he boasts

an undergraduate economics degree from Lviv University, and is reported

to take special pride in designing sophisticated, virtually

undetectable financial frauds that take years to put in place. To pull

them off, he often relies on the human frailties of top bankers, stock

brokers, accountants, business magnates, and key politicians.74

In YBM’s case, for a mere $2.4 million in bribes, Semion and his

henchmen spent years in the 1990s launching a product-free, fictitious

company on the still-badly under-regulated Toronto Stock Exchange.

Along the way they succeeded in securing the support of several leading

Toronto business people and a former Ontario Province Premier to win a

seat on YBM’s board. They also paid the “Big Four” accounting

firm Deloitte Touche very handsomely in exchange for glowing

audits. By mid-1998, YBM’s stock price had gone from less than $0.10 to

$20, and Semion cashed out at least $18 million -- a relatively big

fraud

for its day -- before the FBI raid its YBM’s corporate headquarters.

When

it did so, it found piles of bogus invoices for magnets, but no magnets.75

In 2003, Mogilevich was indicted in Philadelphia on 45 felony counts

for this $150 million stock fraud. But there is no extradition treaty

between the United States and Russia, and no

chance that Russia will ever extradite Semion voluntarily; he

is arguably a national treasure, especially now. Acknowledging these

realities, or perhaps for other reasons, the FBI

quietly removed Mogilevich from its Top Ten Most Wanted list in 2015,

where he had resided for the previous six years.76

For our purposes, one of the most interesting things to note about this

YBM Magnex case is that its CEO was a Russian-American named Jacob

Bogatin, who was also indicted in the Philadelphia case. His brother

David had served

in the Soviet Army in a North Vietnamese anti-aircraft unit,

helping to shoot down American pilots like Senator John McCain. Since

the early 1990s, David Bogatin was considered by the FBI to be one of

the key members of Semion Mogilevich’s Russian organized crime family

in the United States, with a long string of convictions for big-ticket

Mogilevich-type offenses like financial

fraud and tax dodging.

At one point, David Bogatin owned five separate condos in Trump Tower

that Donald Trump had reportedly sold to him personally.77

And Vyacheslav Ivankov, another key Mogilevich lieutenant in the United

States during the 1990s, also resided for a time at Trump Tower, and

reportedly had in his personal phone book the private telephone and fax

numbers for the Trump Organization’s office in that building.78

So what have we

learned from this deep dive into the network of Donald Trump’s

Russian/FSU connections?

First, the President-elect really is very “well-connected,” with an

extensive network of unsavory global underground connections that may

well be unprecedented in White House history. In choosing his

associates, evidently Donald Trump only pays cursory attention to

questions of background, character, and integrity.

Second, Donald Trump has also literally spent decades cultivating

senior relationships of all kinds with Russia and the FSU. And public

and private senior Russian figures of all kinds have likewise spent

decades cultivating him, not only as a business partner, but as a

“useful idiot.”

After all, on September 1, 1987 (!), Trump was

already willing to spend a $94,801 on full-page ads in the Boston

Globe, the Washington Post, and the New

York Times calling for the United States to stop

spending money to defend Japan, Europe, and the Persian Gulf, “an area

of only marginal significance to the U.S. for its oil supplies, but one

upon which Japan and others are almost totally dependent.”79

This is one key reason why just this week, Robert Gates -- a registered

Republican who served as Secretary of Defense under Presidents Bush and

Obama, as well as former Director and Deputy Director

of the CIA -- criticized the response of Congress and the White House

to

the alleged Putin-backed hacking as far too “laid back.”80

Third, even beyond questions of illegality, the public clearly has a

right to know much more than it already does about the nature of such

global connections. As the opening quote from Cervantes

suggests, these relationships are probably a pretty good leading

indicator of how Presidents will behave once in office.

Unfortunately, for many reasons, this year American voters never really

got the chance to decide whether such low connections and entanglements

belong at the world’s high peak of official power. In the waning days

of the Obama Administration, with the Electoral College about to ratify

Trump’s election and Congress in recess, it is too late to establish

the kind of bipartisan, 9/11-type commission that would be needed to

explore these connections in detail.

Finally, the long-run consequence of careless interventions in other

countries is that they often come back to haunt us. In Russia’s case,

it just has.

1Author’s estimates; see

globalhavenindustry.com for more details.

2For an overview and critical discussion, see here.

3See Lawrence Klein and Marshall Pomer, Russia’s

Economic Transition Gone Awry (Stanford University Press,

2002); see also James S. Henry and Marshall Pomer, “A Pile of Ruble,” New

Republic, September 7, 1998.

4See this Washington

Post report, which counts just six bankruptcies to

the Trump Organization’s credit, but excludes failed projects like the

Trump SoHo, the Toronto condo-hotel, the Fort Lauderdale condo-hotel,

and many others Trump was a minority investor or had simply licensed

his brand.

5For example, the Swiss federal and cantonal

corporate registries, available here.

6For ICIJ’s April 2016 “Panama Papers” database

of offshore companies, see here.

7Trump’s minority equity deal with Bayrock was

unlike many others, where he simply licensed his name. See this March 2008 New

York Magazine piece.

8“I dealt mostly with Tevfik,” he

said in 2007.

9Case

1:09-cv-21406-KMW Document 408-1. Entered on FLSD Docket

11/26/2013. p. 15.

10Source.

11Bayrock reported its co-ownership of six Rixos

hotels in a 2007

press release.

12See also Salihovic, Elnur, Major

Players in the Muslim Business World, p.107, and this

Telegraph piece.

13See also Zambia,

Mining, and Neo-Liberalism; Brussels

Times; and Le

Soir.

14According to the Panama Papers database,

“International Financial Limited” was registered on April 3, 1998, but

is no longer active today, although no precise deregistration date is

available. Source.

15According to the Panama Papers, “Group Rixos

Hotel” is still active company, while three of the four companies it

serves were struck off in 2007 and the fourth, Hazara Asset Management,

in 2013.

16Source.

17See also TurizmG�ncel.com

and Le

Grand Soir.

18Case

1:09-cv-21406-KMW Document 408-1. Entered on FLSD Docket

11/26/2013. p. 16.

19The exact date that Sater joined Bayrock is

unclear. A New

York Times article says 2003, but this appears to

be too late. Sater says 1999, but this is much too early. A certified

petition filed with the U.S. Supreme Court places the time around 2002,

which is more consistent with Sater’s other activities during this

period, including his cooperation with the Department of Justice on the

Coppa case in 1998-2001, and his foreign travel.

20See Financial

Times, New

York Times, and Washington

Post. Note that previous accounts of Sater’s

activities have overlooked the role that this very permissive

relationship with federal law enforcement, especially the FBI, may have

played in encouraging Sater’s subsequent risk-taking and financial

crimes. See here.

21See here,

p. 13.

22Sater’s 1998 case, never formally sealed, was

U.S. v. Sater, 98-CR-1101 (E.D.N.Y.) The case in which Sater secretly

informed was U.S. v. Coppa, 00-CR-196 (E.D.N.Y.).

See also this

piece in the Daily Beast.

23Source.

Sater also may have taken other steps to conceal his criminal past.

According to the 2015 lawsuit filed by x Bayrocker Jody Kriss, Arif

agreed to pay Sater his $1 million salary under the table, allowing

Sater to pretend that he lacked resources to compensate any victims of

his prior financial frauds. See Kriss

v. Bayrock, pp. 2, 18. The lawsuit also alleges

that Sater may have held a majority of Bayrock’s ownership, but that

Arif, Sater and other Bayrock officers may have conspired to hide this

by listing Arif as the sole owner on offering documents.

24See here,

p. 155.

25“Former FL Group manager,” interview with

London, August 2016. Sigrun Davidsdottir, Iceland journalist.

26See “Report

of the Special Investigation Commission on the 2008 Financial Crisis”

(April 12, 2010).

27These loans are disclosed in the Kaupthing

Bank’s “Corporate Credit -- Disclosure of Large Exposures > €40

mm.” loan book, September 15, 2008. This document was disclosed by

Wikileaks in 2009. See this

Telegraph piece. http://file.wikileaks.info/leak/kaupthing-bank-before-crash-2008.pdf,

p.145 (€79.5mm construction yacht loan to Russian vodka magnate Yuri

Shefler’s Serena Equity Ltd.); p. 208 (€45.8 mm yacht construction loan

to Canadian-Russian billionaire Alex Shnaider’s Filbert Pacific Ltd.).

28Kriss lawsuit, op. cit.; author’s analysis of

Kaupthing/ FL G employees published career histories.

29Author’s interview, “Iceland Economist,”

Reykjavik, July 2016.

30Source.

The passage in Russian, with the father’s name underlined, is as

follows: “Родители Алекса Шнайдера владели одним из первых успешных

русских магазинов в русском квартале Торонто. Алекс помогал в бизнесе

отцу -- Евсею Шнайдеру, расставляя на полках товар

и

протирая полы. С юных лет в Алексе зрела предпринимательская жилка.

Живя с родителями, он стал занимать деньги у их друзей и торговать

тканями и электроникой с разваливающимися в конце 80-х годов советскими

предприятиями.” “Евсею Шнайдеру” is the dative case of “Евсей Шнайдер,”

or “Evsei Shnaider,” the father’s name in Russian.

31The Zurich company

registry reports that “Seabeco SA” (CHE-104.863.207) was

initially registered on December 16, 1982, with “Boris Joseph

Birshtein, Canadian citizen, resident in Toronto” as its President. It

entered liquidation on May 5, 1999, in Arth, handled by the Swiss

trustee Paul Barth. The Zurich company registry listed “Boris Joseph

Birshtein, Canadian citizen, resident in Toronto,” as the President of

Seabeco Kirgizstan AG in 1992, while “Boris Joseph Birshtein, Canadian

citizen, resident in Zurich,” was listed as the company’s President in

1993. “Boris Birshtein” is also listed as the President and director of

a 1991 Panama company, The Seabeco Group, Inc. as of December 6 1991.

See below.

32Source.

33The Zurich company registry reports that

“Seabeco SA” (CHE-104.863.207) was initially registered on December 16,

1982, with “Boris Joseph Birshtein, Canadian citizen, resident in

Toronto” as its President. According to the registry, it entered

liquidation on May 5, 1999. See also this.

The liquidation was handled by the Swiss trustee Paul Barth, in Arth.

34For Seabeco’s Antwerp subsidiary, see here.

35“Royal HTM Group, Inc.” of Toronto, (Canadian

Federal Corporation # 624476-9), owned 50-50 by Birshtein and his

nephew. Source.

36Birshtein was a director of Seabeco

Capital Inc. (Canadian Federal Incorporatio # 248194-4,) a

Winnipeg company created June 2, 1989, and dissolved December 22, 1992.

37Since 1998, Boris Birshtein (Toronto) has also

served as Chairman, CEO, and a principle shareholder of “Trimol Group

Inc.,” a publicly-traded Delaware company that trades over the counter.

(Symbol: TMOL). Its product line is supposedly “computerized photo

identification and database management system utilized in the

production of variety of secure essential government identification

documents.” See Bloomberg.

However, according to Trimol’s

July 2015 10-K, the company has only had one customer, the

former FSU member Moldova, with which Trimol’s wholly owned subsidiary

Intercomsoft concluded a contract in 1996 for the producton of a

National Passport and Population Registration system. That contract was

not renewed in 2006, and the subsidiary and Trimol have had no revenues

since then. Accordingly, as of 2016 Trimol has only two part time

employees, its two principal shareholders, Birshtein and his nephew,

who, directly and indirectly account for 79 percent of Trimol’s shares

outstanding. According to the July 2015 10-K, Birshtein, in particular,

owned 54 percent of TMOL’s outstanding 78.3 million shares, including

3.9 million by way of “Magnum Associates, Inc.,” which the 10-K says

only has Birshtein as a shareholder, and 34.7 million by way of yet

another Canadian company, “Royal HTM Group, Inc.” of Ontario (Canadian

Federal Corporation # 624476-9), which is owned 50-50 by Birshtein and

a nephew. It is interesting to note according to the Panama Papers

database, a Panama company called “Magnum Associates Inc. was

incorporated on December 10, 1987, and struck off on March 10, 1989. Source.

As of December 2016, TMOL’s stock price was zero.